by Andrea Fioravanti

For eleven years Matteo Pericoli has been teaching students around the world how to analyze the narrative structure of a story and creatively and imaginatively transform it into a building. Out of this experience came “The Great Living Museum of the Imagination” (il Saggiatore), itself written as if it were a museum to explore, complete with a map and bookshop

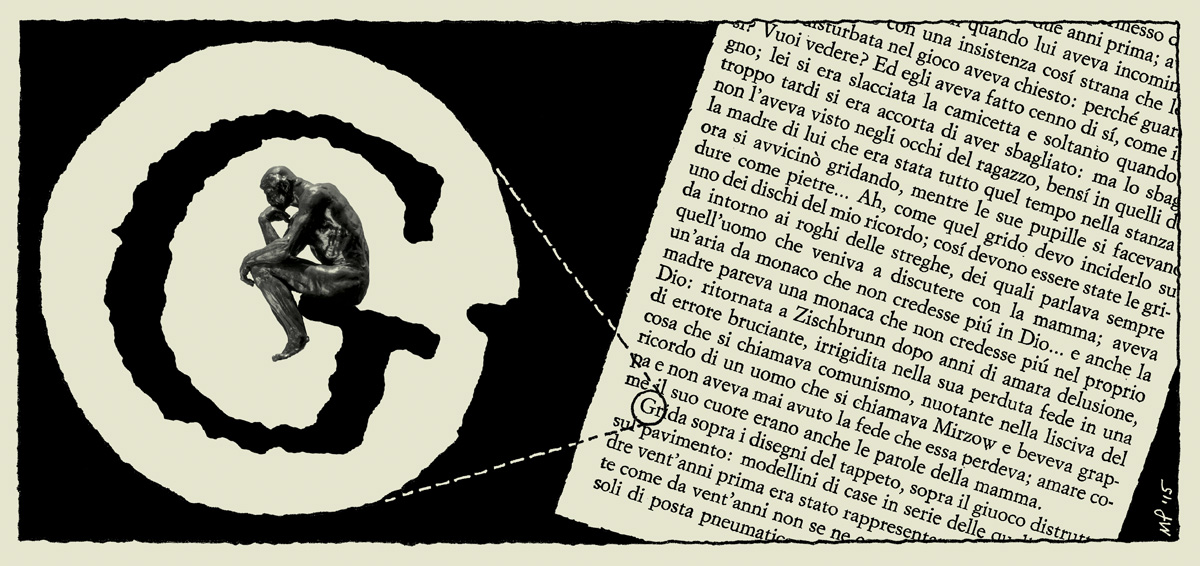

Dickow, Niddam, Porat, Topaz based on a short story by Yonathan Raz Portugali – Hebrew University of Jerusalem

For Ennio Flaiano, the great books are not the ones we browse carelessly, consume out of envy or emulation, finish in haste, in anger, to keep up with the literary fashion of the moment; they are the ones we read so many times that we inhabit them, feeling them on us like certain corners of our house. We keep them on the bedside table, in our purse or on a precise shelf in the bookstore to take refuge when we need them most. To seek answers to questions that life distractedly poses to us. Some books are shaped like a tent, some like a penthouse, some like a house on a hill.

However, it took the multifaceted nature of an architect, illustrator, teacher and writer to discover how to analyze the architecture of a story and transform it with creativity and imagination into a building. For eleven years Matteo Pericoli has been guiding students all over the world (the United States, Italy, Israel, Switzerland, Taiwan and the United Arab Emirates) in a game that has now become a surprising experiment where there are no mistakes, because there is no dogma to follow: the Laboratory of Literary Architecture. This multi-year work has become a book: “The Great Living Museum of the Imagination” (il Saggiatore), written in turn as if it were a museum to explore, complete with a map and bookshop.

n this generous guide that is attentive to the reader’s pace, Pericoli reveals the secrets to opening up to the mysterious but continuous link between fantasy and construction. And so Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness becomes a soaring inverted pyramid whose apex lies dozens of feet underground; Elena Ferrante’s L’amica geniale is transformed into two buildings that support and repel each other. And so on it goes, building. This cultural construction site does not end with the book, but expands into a constantly updated bilingual site.

“Eleven years ago a flame was lit in me, igniting a fuse whose effects I had not foreseen. I had just returned from the United States, and when I was offered a workshop at the Scuola Holden, at the time a small space on Via Dante in Turin, I decided to delve into a concept that had been rattling around in my head. Why is it that a story is said to have structure, to have a foundation, or to “not stand”? Yet I realized that in talking with students about narrative structures, words were not enough. There was an amount of information that was missing. So I asked them, ‘Why don’t you show me using cardboard, scissors and glue?’ This trivial question led me to a surprising discovery.”

Which discovery?

We all have a giant underground reservoir of unexplored knowledge. A cauldron of creative energy given by reading that we often fail to access because if we go to search for it with words we only dig up the same concepts that we had worked out in the past by copying other people’s thoughts. Instead of continuing to use words to explain something that was made of words, we try to give tangible form to our thoughts about the book. By doing so, I have noticed that knowledge increases tenfold. And it applies to everyone. From the high school students who take my classes to those who have not read as many books or are not familiar with architecture. This phenomenon is repeated at every workshop.

Let’s pause for a moment at the entrance of this museum-book in which you invite the reader to leave in the wardrobe the cumbersome baggage that prevents a better understanding of the links between stories and architecture. What are the most difficult obstacles to leave behind?

For example, thinking that the relationship between architecture and literature is an insurmountable intellectual endeavor; not feeling up to it and necessarily proving that you are intelligent and prepared before reading a book. But above all, skepticism; the same skepticism I encounter at the beginning when I propose this game. At the first workshop meeting I see some dismayed, terrified faces. Then on the second and third day I am overwhelmed by the crazy enthusiasm of those who understand how good it feels to be on the other side.

On the other side with respect to what?

With respect to preconceptions. Beyond our prior knowledge about style, narrative, the labels we give to books. Stories are not punctual roads to be traveled based on directions given by others, but buildings to be explored freely, immersing ourselves in a literary space. Obviously this space is constructed by someone else, the writer, but in the end the constructions are almost entirely done by us, in our own minds. The hope is that once the museum-book begins the reader will say, you know what? I’m going to leave these bulky bags there and come out lighter than when I went in.

So let’s go in light and give an example of an architectural construction inspired by a narrative structure.

During a workshop, I was struck by the different ways in which Ernest Hemingway’s short story “Hills Like White Elephants” can be viewed. For the architects, the love story between the two characters was square, like a parallelepiped, while for the high school kids it was cylindrical, perhaps more idealized. These responses fill your mind and body with a positive feeling, because with a text they would not have been able to deepen the relationship between the two main characters like that. The same happened with Amy Hempel’s extraordinary short story entitled “The Harvest.” In eleven years of the Laboratory of Literary Architecture, no two buildings ever looked alike. The point is that our thoughts have a pre-verbalized shape and feeling, different for everyone, which we often ignore, jumping immediately to the next step to feed our inner monologue. The workshop enhances what the written words deflate. There are continuous results because this process is something extremely natural that only comes out if we relax.

Could this innovative approach be used in schools to bring young people, as well as older people, closer to reading?

Certainly. Realizing that reading is similar to exploring a place whose ultimate shape is embedded in our synapses might be a drive to approach stories in a different way. That is, not trying to replicate what others have previously said or thought about that book. Because a work has been presented to us as beautiful, ugly, simple or complex, we should not look for a feeling in the text that others have already found. We know much more than we think we know. By going back to the source of ideas that have weight and form, we can all find our own spaces, building, deconstructing, tearing down and starting over. And mistakes no longer exist; there are no teachers and no students.

In the book you delve into two important concepts that literature and architecture share: emptiness and context.

Architecture is the constant companion of our entire existence. We spend our lives crossing, passing through buildings and spaces one after another. To understand them we talk about styles and forms, but we often neglect the most powerful effect of architecture: what is not there. Our rooms are surrounded by walls, but we live and work within the one space that has not been built. And so also in stories we give so much importance to pages, paragraphs, sentences and words, neglecting how important the space within a story is. An ineffable element that we have to reconstruct in our minds. And how we do that necessarily depends on the context. Not only the one within which the book or building escapes, but also my context: everything I have learned, heard, believed so far; my expectations and ideas that make me always approach the story or space differently according to my existential condition at that moment. Focusing on different details and spaces each time.

You talked about how much architecture is in literature, but how much literature is in architecture?

Architecture is impregnated with narrative. Each compositional choice made by whoever designed the spaces we live in (from the sequence of volumes to their connections, from what is revealed to what is concealed, from the impact of light to the mystery of darkness, and so on) is actually a narrative choice, sometimes made consciously and sometimes not. Architecture then determines the narrative of our day. Think of the moment when you cross the threshold and leave your house in the morning: in your head you think something new is beginning but that something actually does not exist because outside the door nothing has begun and nothing has ended, everything has always existed. Architecture is our device for framing our daily narrative: opening the window to change the air in the morning, leaving the house, returning home, going up the stairs, going down the stairs. This interaction with architecture is unconscious but deeply narrative and determines how we frame the narrative of our lives. Every movement we make is a reading of space, and without knowing it we are already able to understand the concatenation of narratives of the architecture around us. Why do we exit a building and go right instead of left?

And by instinctively knowing architectural spaces are we able to analyze narrative structures?

Yes, everyone in their own way gives meaning to different elements by privileging one over the other. The door has a clear narrative potential, but for someone the height of a ceiling may be important. A window put in the right place may be a revelation for someone. But if you convey that to another narrative need, it doesn’t work at all. Imagine the first time someone with a hammer or sledgehammer knocked down a piece of wall in a building of any kind, primordial or otherwise, and saw the world outside without being able to walk through it. Who knows, maybe every architectural element has its literary counterpart, after all, that’s how stories are born.

Castelli di carta | Guida all’architettura letteraria per esplorare in modo innovativo i libri (e sé stessi)

by Andrea Fioravanti, published on Linkiesta on November 26, 2022:

https://www.linkiesta.it/2022/11/museo-vivente-immaginazione-pericoli-saggiatore/