Matteo Pericoli Gorgeously Illustrates Writers’ Views and Workspaces

By Maddie Crum

BOOKS, HuffPost, November 18, 2014

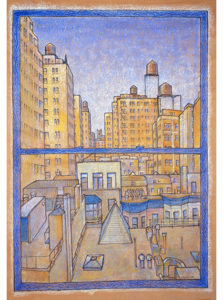

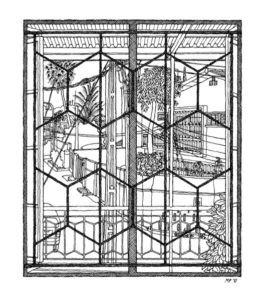

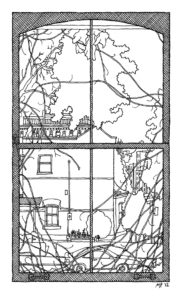

Matteo Pericoli is an architect and illustrator. He began sketching window views after moving out of an apartment he’d lived in for nearly a decade, and realizing that he’d never gaze out at the same spot again. His latest book, Windows on the World, collects his drawings of writers’ window views, accompanied by their short descriptions of the views’ importance. Some capture the quotidian — power lines and garden supplies — while others feature major historical landmarks. Pericoli spoke with The Huffington Post about his project and his favorite window views.

What inspired you to begin your Windows on the World project?

After all these years spent drawing window views, I’ve come to the conclusion that contemplating a window view isn’t so much an action directed outward, but inward, one of reflection. The view looks back at you, and asks: “Why are you here? Is this really the place (in the world, in your life) where you want to be? How did you get here? (Both practically and metaphorically.)”

That’s what happened to me ten years ago when I was moving out of our Upper West Side apartment and suddenly realized that I would have lost forever the window view I’d been looking at (mostly unknowingly) for seven years. That’s when I realized that that particular view symbolized my life path and decisions made up to that point. And that’s when I told myself, “Now I have to draw all of the window views of the city!” Obviously I never did that, I just drew 63 (out of a hundred plus I had visited) that were after published in a book called The City Out My Window: 63 Views on New York. In the seven years prior, I had worked on long scrolls depicting Manhattan as seen from its surrounding rivers and from Central Park. My goal had always been to try to draw the whole city, yet I never imagined that what I had been looking for was instead the reverse process, i.e. to draw how people see the city, rather than what the physical city looks like.

I decided that there are two kinds of window views: active and passive. If you feel that your choices have brought you to where you are at that very moment in time and space (i.e. the viewpoint provided by your window), then the narrative around the view is active. If that’s not the case, it’s a passive view. Children’s window view drawings and texts are among the most telling because theirs are quintessentially passive views, thus we can infer a great amount of information about how children perceive their place in the world from their particular perspectives (literally).

When I was working on the New York window view book, I realized that writers had a similar relationship to their views as mine. Mostly stuck at their desks, they would either position themselves near a window in order to take in as much as possible, or would consciously choose to protect themselves from it. And when I asked them to describe their views, something extraordinary happened: all the elements that I had been able to capture in my drawings were complemented — even augmented — by their words. This was the simple premise of the Windows on the World project: drawings of writers’ window views from around the world accompanied by their texts — lines and words united by a physical point of view.

You’ve said that photographing the windows didn’t always suffice. What you wanted to capture was the way you emotionally perceived your view, too. So what was the process of drawing writers’ windows like? (Did you ask them to submit photos, describe them with words, etc.?)

Back to my Upper West Side view from ten years ago. When I realized that I couldn’t leave the view behind, that it was too much a part of me, I thought, “Wouldn’t it be great if I could peel an imaginary film off the window and take everything with me, window frame, glass, view, and all?” I tried photographing the view, but (perhaps I am a bad photographer, or maybe for technical limitations) what I was getting was either the window itself or what was beyond the glass, not both, or at least I was not getting my mental image of it. If you open the window and take a picture, you see an urban landscape; if you photograph the frame, you mostly see the frame. A window view is both.

So just like with my long skyline drawings, the only way for me to reproduce a window view is to obtain as many photographs as possible, use them to mentally reconstruct the view, i.e. the space between the sheet of glass and all the physical elements that constitute the view, and rebuild it as a line drawing. Often the writers’ photos came with descriptions, but often it would end up the other way around: i.e. I would be the one describing the window views to them with my drawing.

Drawing (and especially hard line drawing) is first and foremost a process of synthesizing information. Each line is the result of a selection, a series of omissions in order to tell the most with the least. It’s a process that requires a lot of preparation and investment and yields a “low artistic return,” so to speak. For example, Saul Steinberg’s drawings are among some of the most beautiful works of art, and yet the majority of them are “simple” line drawings with most of the effort made before each line was placed on the paper.

Do you find that there’s often a disconnect between the way we conceptualize a space and the way it “actually” looks?

This is an interesting question. Prior to forming a concept of space, it must first be perceived. And we do that all the time. I am doing it right now, as the artificial light just in front of me is reflecting by the walls around my tiny workspace and the sound of my typing on the keyboard also reverberates off them. With my peripheral vision I monitor the light coming from a not-so-close window to my left. And we do the same when we walk out in the street or through a square (by subconsciously selecting to walk closer to the buildings rather than in the middle of the open space). Whenever we encounter a space (which happens hundreds of times a day), we take it in via our senses. So we actually experience and therefore know architecture much more than we think we do, because space — i.e. nothingness — is constantly being perceived. We see what’s constructed; we perceive what’s not there: space.

In fact, when we talk about what a space “looks like,” we often refer to the physical, tangible aspects of architecture — i.e. what forms space: walls, openings, glass walls, slabs, roofs, etc. — rather than space itself. Just as in other disciplines, what is not physically there is often as important as what is there. A window view is nothing but a hole in the wall through which we can form an idea of the world we live in.

I teach a course called Laboratory of Literary Architecture (LabLitArch.com) in which we imagine removing all the words from literary texts and look at what is left. As in architecture, once you remove the skin — the “language” of walls, roofs, and slabs — all that remains is sheer space. In writing, once you discard language itself, what’s left? What we discover is that the use of architectural metaphors to describe literature (e.g. the architecture of a novel) is not a coincidence: the effort of writing, putting a word after the other in order to build sentences, is very similar to that of constructing a building. The words are used to envelop a literary space that is perceived by the reader, very much like architectural space. By building an architectural model of the literary structure we simply reveal this process.

What were some of the most compelling responses you received from authors?

Receiving the texts from the writers, especially after they had seen my drawing of their window views, was always a truly exciting moment. It was like the closing of a circle; everything made sense. All the things I had stared at, and then drawn, trying to make sense of every single detail, would finally come together. Sometimes, and when it happened it was a lot of fun, someone would thank me for having revealed his/her window to him/her. I recall Marina Endicott, who had doubts about her view being as good as the others, telling me, “You were right, I no longer have view envy.” That was so nice. It’s as if we judge views only by how photogenic they are. Until Ms. Endicott had the chance to write about her view, it had not been so visible to her.

It does happen that sometimes we need to be shown things that are near us to notice them. Or that we notice them when they are gone. And often that’s the case with a window view. It’s hard to sit down in front of it and pay full, true and dedicated attention to it. I mean, it’s always there, I can do it any time I want, why take the time to pause and look? And that’s when things slip by in life. That’s why I would love to go back to my view when I was a little kid growing up in Milan and look at it now, with this recent window obsession of mine. I am sure that, like the sudden resurfacing of a familiar smell, a wave of past and intense feelings would rush through me. Isn’t that nice?

What does your own workspace look like? Do you have a view that you enjoy?

My workspace is the former inside of a walk-in closet. Actually, it’s no longer the inside of the closet as the space now opens up into our bedroom. When we moved in, we tore down a wall between the closet and the bedroom to create my workspace, so technically I am neither in the bedroom nor inside the closet, but kind of in between. My computer desk, i.e. where I am now, is right in front of the door of the former walk-in closet, which can’t be opened now. The most beautiful thing about my workspace is that I had someone cut out a small 14” x 10” glass-less opening in the door just in front of where I sit. This “window” has a small door of its own which can only be opened from the inside, i.e. by me, with a little latch and it’s exactly at the height of my daughter Nadia, who is eight now. So when I hear “knock, knock” and I open my small “window,” I see her smiling face occupying the whole view. Should we ever leave this place, this is the view I’ll miss more than any other.

Orhan Pamuk’s view of the Aya Sofia is breathtaking — he writes that he’s often asked if he grows tired of such a beautiful view, and he says no. On the other hand, Karl Ove Knausgård says he enjoys repetition, and prefers his more mundane view. Do you think an ideal view is awe-inspiring, or commonplace and meditative — a way of clearing our minds?

I don’t think there is an ideal view. There are probably ideal views for different occasions and for different people. For example, if I am happy someplace, at that very moment in time, I know that I’ll absorb the view I am looking at (whatever kind it may be) and turn it into a fantastic view, one that I’ll associate with a positive moment in my life. I think that views do serve as a kind of reset button, the same as when we blink; we need a moment to pause to then move on. For that purpose, all views are the same, because we don’t actually pay attention to them when we look at them, we are just using them.

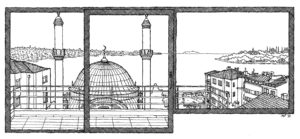

If you want instead to spend time observing, obviously expansive and photogenic views are great. But being awe-inspiring means that they are often great landscapes, and as a result do not necessarily make great drawings, because a line drawing will not add anything to the landscape. If I have to draw a view, I look for intricate, unexpected, urban (more often than rural, but it’s not a rule) views that offer unique perspectives onto the world. Orhan Pamuk’s view has the compositionally incredibly important mosque right there, just outside the window. Yes, beyond it it is breathtaking, but without the mosque and the two minarets just beyond the terrace, it would be much less interesting (for me). For the New York window view book, I visited an amazing apartment overlooking Central Park. The view from the living room window was so spectacular that I realized I couldn’t draw it. I knew the drawing wouldn’t have added anything that we didn’t already know about how beautiful Central Park is when viewed from a high floor. On the other hand, a friend almost refused to open the curtains to show me his view of a derelict fire escape above a small courtyard facing other windows and another fire escape. I spent days drawing all the bricks of the opposite building and all the squiggly lines of the fire escapes and, well, he ended up loving his view afterwards. He even told me that he started keeping the curtains open in order to take his view in!

Do you have a favorite window or view?

Of course. I see it every day when my daughter returns from school and knocks on my mini closet-door-window.

Read from the HuffPost website: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/windows-on-the-world-book_n_6173178