Exactly twenty years ago today, on October 28th, 2001, CBS Sunday Morning aired a five-minute piece on Manhattan Unfurled.

In Conversation with Dina Nayeri

Inventing Truth with Words and Lines

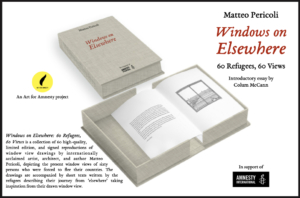

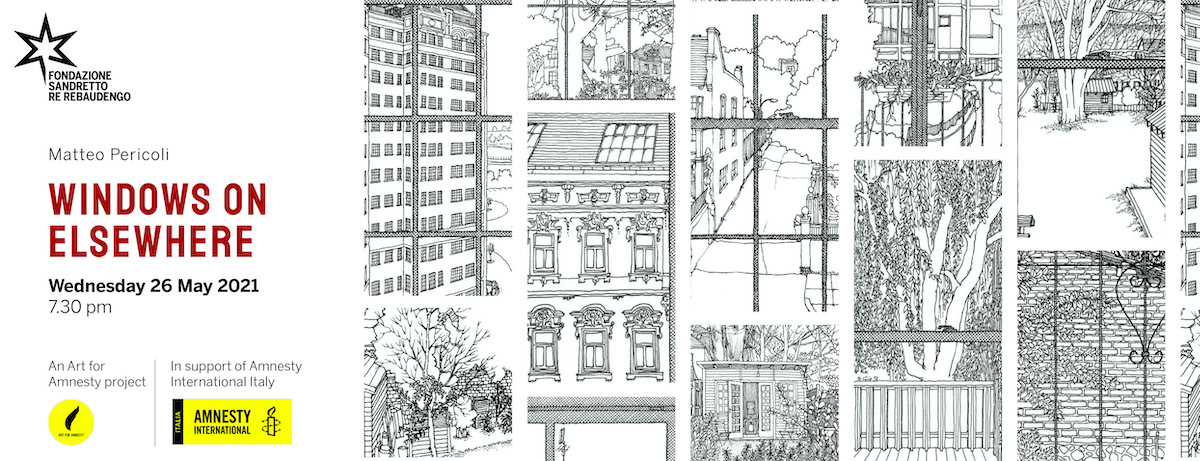

Whether in art or literature, what does it mean to tell the truth, or a version of the truth? And what might it mean to invent the truth in the service of a higher truth? Looking to Matteo Pericoli’s Windows On Elsewhere: 60 Refugees, 60 Views, a project with a collection of 60 window view drawings by Pericoli depicting the present window views of 60 persons who were forced to flee their countries, as well as looking to Dina Nayeri’s book, The Ungrateful Refugee, we will explore the role of invention (or “artful fudging” as Pericoli put it) in creation.

Bill Shipsey from Art for Amnesty and Alice McCrum from the American Library in Paris will moderate the conversation.

Free event. Click here to reserve a ticket.

Location

The American Library in Paris

10 Rue du Général Camou

75007 Paris

France

Camila Raznovich interviews Matteo Pericoli

The official website of the Windows on Elsewhere project is online.

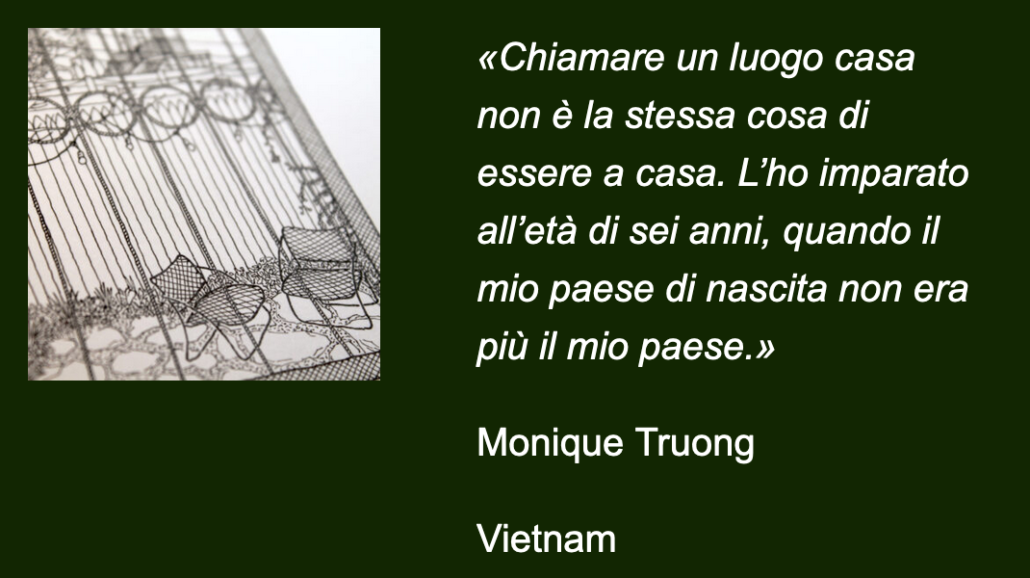

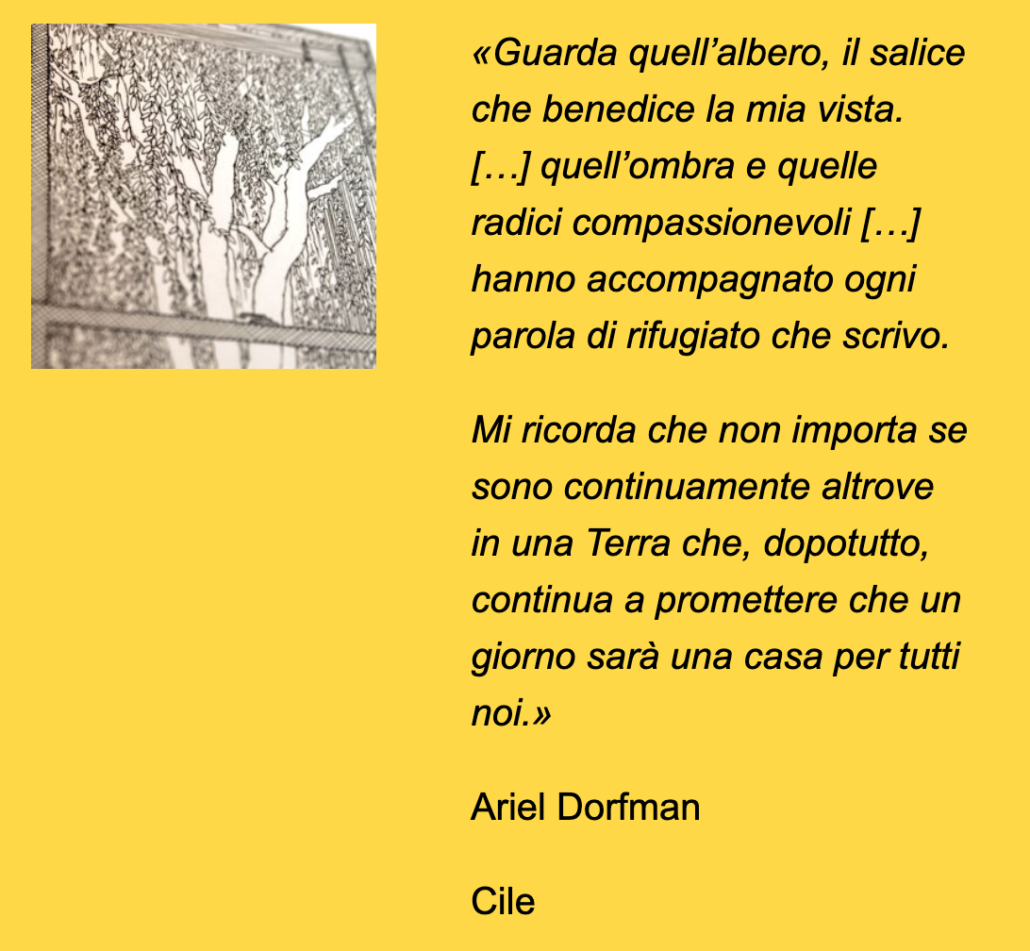

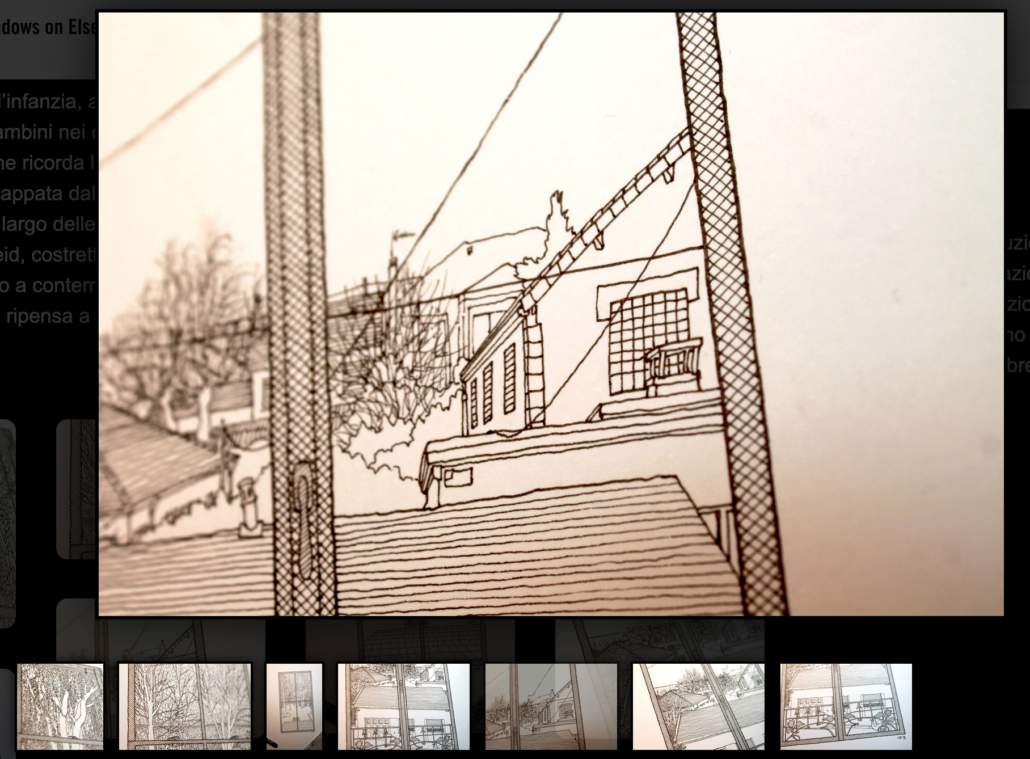

Windows on Elsewhere: 60 Refugees, 60 Views is a book, exhibition, and limited-edition print project with a collection of 60 window view drawings by Matteo Pericoli, depicting the present window views of sixty persons who were forced to flee their countries. The drawings are accompanied by short texts written by the refugees describing their journey from ‘elsewhere’ taking inspiration from their drawn window view.

On the surface, the drawings simply reveal the view of each refugee framed by their window. But as we read their accompanying words our attention turns inward and we get a glimpse of their past, their experiences, their emotions, and of the people, places, and stories left behind— inevitably blended with a seemingly everlasting, fleeting present.

The refugee participants in the book, who come from over thirty countries, describe what it feels like to be forced to abandon one’s home, one’s country, and, in many cases, one’s loved ones. Their stories are deeply personal and emotional and draw out the complexity, intensity and pain that are ingrained in a refugee’s journey.

The website was produced by Amnesty International Italia in collaboration with Art for Amnesty, producer of the project.

Photographs from the opening of the Windows on Elsewhere exhibit at the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin (Italy)

(Courtesy of the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo)

Finally, after 3 years of work, “Windows on Elsewhere: 60 Refugees, 60 Views”, a project I worked on with Art for Amnesty, will be exhibited in Turin. The project is in support of Amnesty International Italia on the occasion of Amnesty’s 60th anniversary.

On Wednesday, May 26, the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo will inaugurate the exhibit of 60 drawings accompanied by 60 texts written by the refugees in which they share what they see from their windows, but also memories of their journeys, of what they have left behind and their hopes (the exhibit ends on July 28).

The following day, the book Finestre sull’altrove, 60 vedute per 60 rifugiati, published by Il Saggiatore will go on sale. The Lavazza Group has generously contributed by supporting the production of a series of limited edition box sets of the drawings and texts in Italian, English, French and Spanish (60 per language), which will be sold to benefit Amnesty.

The Lavazza Group has generously contributed by supporting the production of a series of limited edition box sets of the drawings and texts in Italian, English, French and Spanish (60 per language), which will be sold to benefit Amnesty.

Click here to visit the project’s official website.

Ho provato qui a rispondere alla casa editrice EDT sul quale potrebbe essere il mio personale “punto di ripartenza”, o un’“idea di ripartenza”:

https://www.edt.it/ioriparto-matteo-pericoli-affacciarsi-al-futuro

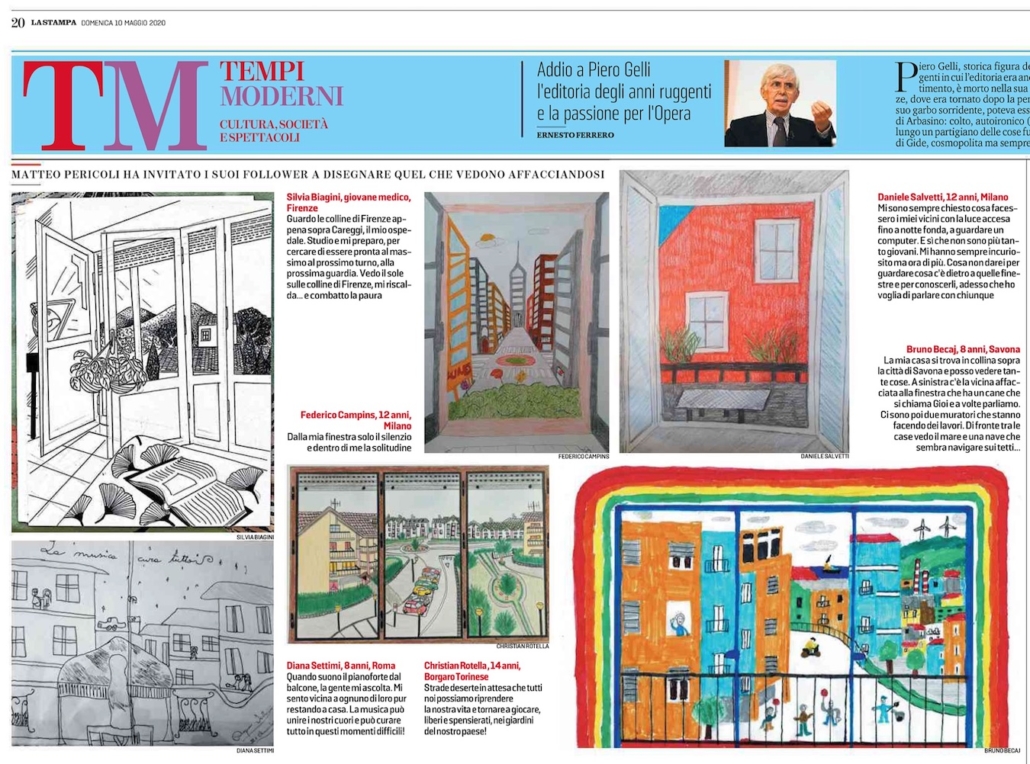

Il nostro punto di contatto col mondo svuotato dal virus

di Matteo Pericoli

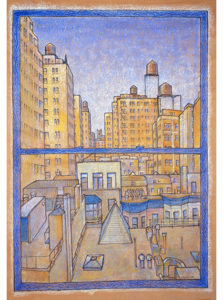

È tutto iniziato nel 2004 a New York quando, a pochi giorni dal trasloco, preso dallo sgomento di abbandonarla dopo setti anni passati con lei, silenziosa e trasparente, sempre al mio fianco decido di disegnarla in fretta e furia, per portarmela via, per non lasciarla indietro, per mantenere vivo quel rapporto così intenso. Mentre la disegno mi accorgo però che, sebbene l’avessi vista per anni, non l’avevo mai osservata a fondo. Noto, infatti, una moltitudine di dettagli che mi erano sfuggiti. Mi rendo conto che avevo dato per scontato la vista dalla mia finestra.

Da allora si potrebbe dire che disegno quasi solo finestre, cerco cioè di restituire in un disegno quello che altre persone vedono dalle loro finestre per poi “raccontarle”. Nella maggior parte dei casi disegno viste di luoghi che non ho avuto la fortuna di visitare e di persone che ho a malapena conosciuto.

È così che ho scoperto Torino quando ci trasferimmo qui dodici anni fa. È così che ho “viaggiato” per il mondo e disegnato finestre di scrittori e scrittrici che vivono in India, Giappone, Islanda, Nigeria o Argentina. È così che, da poco più di un anno, grazie un progetto per Amnesty International, sto imparando a vedere anche quello che vedono i rifugiati quando guardano fuori dalle loro nuove finestre.

In fondo, in tutti questi anni sono stato alla ricerca della conferma, o forse della spiegazione, di quel profondo legame che mi aveva spinto a disegnare la mia, di vista, nel 2004.

Poi, circa due mesi fa, succede l’inimmaginabile: improvvisamente, impreparati, impauriti e senza un attimo di preavviso ci troviamo tutti in casa ad attendere e a sperare. Di colpo lo sguardo dalle nostre finestre si trasforma. Questo strano “oggetto” che io avevo osservato, disegnato, ascoltato per 14 anni diventa la nostra principale inquadratura su un mondo svuotato: il nostro punto di contatto, di separazione, di protezione, e di speranza e unione.

Da questo semplice riquadro, in fondo null’altro che un buco nel muro che avevamo forse trascurato in passato, ora migliaia, milioni di sguardi si intrecciano l’uno con l’altro per ricostruire quella densa trama che era la vita precedente alla quarantena. Di slancio chiedo sulla mia pagina Facebook di approfittare di questo periodo bloccati dietro alle nostre finestre per provare a disegnarle e a raccontarle.

Ho ricevuto una moltitudine di lavori, e tra quelli che ho condiviso è venuto fuori quello che in tutti questi anni avevo sospettato, ovvero che le finestre offrono più livelli di lettura: collocando il nostro sguardo in un preciso punto della nostra vita, possiamo muoverci liberamente nello spazio e nel tempo; il confine tra passato e futuro sembra confondersi; come in uno specchio, la nostalgia e la speranza si riflettono verso di noi. Tutto sembra fondersi in un grande e illimitato potenziale narrativo del quale per anni avevo avuto solo il sentore.

In questa pagina potete vedere solo alcuni esempi tra gli intensi e commoventi lavori che ho ricevuto. Sono grato a tutti coloro che mi hanno mandato le loro finestre. D’ora in poi, ogni mio disegno di una qualsiasi vista da una qualsiasi finestra sarà arricchito da ciò che ho imparato e sentito in questo periodo. Guardare dalla finestre non sarà più come prima, e mi auguro che sia così per tutti.

The other day my friend Azzurra Muzzonigro asked me to contribute a short piece about how my work space and routine are overlapping with my family’s domestic life and space in our Turin (Italy) apartment during the lockdown for a feature on her blog called “Domestic space is the new public space”. Here’s what I told her.

My current daily routine is actually very similar to my previous one, seeing that I basically work in a large closet at the end of a long hallway from which we removed a wall so that I could access it from the adjacent bedroom rather than from the door. When we moved in, we had a small opening, a “window” of sorts, cut into the door at the end of the hallway at the height of my daughter’s face (who at the time was seven years old), which ended up right at my eye level, so, upon her knocking, I could open the little panel that covered the opening and see her smiling face perfectly framed in my own “little window”. Luckily, I still have a “real” window in the bedroom next to my studio/closet that looks at the now quiet and deserted outside world (and much further away the hill of Superga).

What is different now is that my little studio/closet window, which opens onto the hallway, is being opened and closed a lot more often, because beyond it there’s a lot more life. I hadn’t thought about it, but this opening has become my true inside/outside view onto a series of intense intra-domestic movements: my wife going from one room to the other, ending up in the living room where she works and where she holds her lessons; my daughter wandering from room to room before ending up in her bedroom where she tries to recreate her social and academic life. There’s actually a great coming and going right before me. And this little window that until just a few weeks ago was used mostly to keep an eye on what the cats were doing (usually sleeping) — or to throw them a crumpled up piece of paper so they would quit bothering me, or that I would use to say hello to whomever was coming in from the front door (at the other end of the corridor) — has now become my primary window looking out at a home bustling with life and activity, full of new and complex interactions; of inventions and revelations; of hope and anticipation; and, sometimes, of tension and anxiety. Even the cats are more active. Well, Ralph, the male, isn’t, he still sleeps a lot; but Marlene, the female, doesn’t seem to understand why we’re always around, why this small window that used to stay mostly closed gets instead opened all the time; and why these weekends are lasting an eternity.