On Line Drawing — Pagina99

by Matteo Pericoli

More than anything else, I believe that line drawings reveal more clearly the decision-making process, the omissions: a line drawing must speak clearly, purposefully, and synthesize reality. Other techniques, such as sketching, painting, and photography, have a more direct, one could say, relationship with reality. They try to transfer as closely as possible onto the medium (paper, canvas, wood, etc.) the way our brain sees the world. A line drawing instead, before being produced, goes through an additional, narrative process during which the draftsperson asks herself such questions as: “Do I need to add another line in order to show what one line is already showing?” Or: “How many lines do I need in order to describe this detail as clearly as possible without drawing too many lines?”

Line drawings are obviously closely related to, and derive from, architectural drawings — i.e. technical and detailed drawings that have strong language-like rules. In fact, they are documents (as in construction documents) that convey very precise information about both the aesthetic appearance as well as the materials of a building. The clearer the architectural drawing, the easier it will be for the observer to appreciate its compositional qualities or its construction technique.

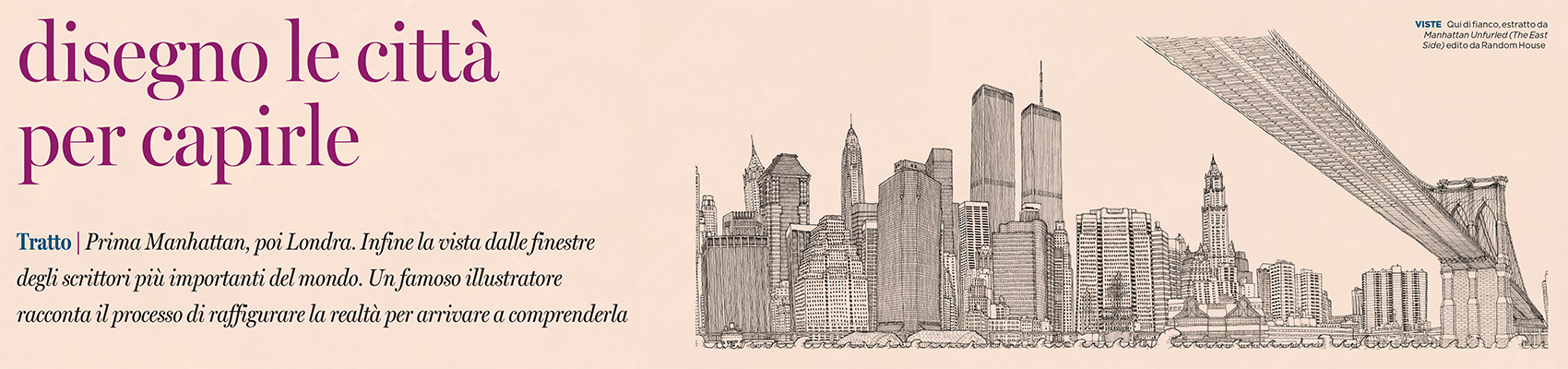

I was still working at Richard Meier’s architectural studio in New York when I decided in 1998 to try and use the very kind of architectural descriptive lines I had been using at the office to describe the island of Manhattan in its entirety. I had just taken the Circle Line boat tour around the island to see what had previously been invisible to me until that point (by being inside it): the city itself. Thus I tried to transfer the slow, revelatory progression of the boat experience into a similarly long and slow-progressing drawing (it takes years to complete these unfurled drawings) that would show everything rather than something. In fact, the issue I had been grappling with since I’d moved to New York in 1995 was that the city seemed to be too hard to grasp as a whole. It could be described in pieces, sections, areas — the famous buildings standing above everything else with little relationship with the whole. “What would drawing everything, without any selection, feel like in the end?” I asked myself. “And if I draw everything with as few lines as I can, with funny waves, and without measuring or using a ruler, will the result be a drawing that kids would want to color and interact with?”

Line drawing is first and foremost a cognitive tool. By drawing everything, I was hoping to understand and therefore share the city as a whole. I realized, of course, that the whole of Manhattan Unfurled was much more than the sum of its parts. That by drawing everything you end up learning a lot, yet it’s hard to explain what that is with words. It’s a different kind of knowledge. The same happened with London Unfurled, my other large urban project. Cities, and especially large cosmopolitan cities, afford a unique opportunity to draw the most intricate, complex and interesting range of architectural ideas at once. In the case of London, I went from knowing practically nothing about a city where I had never lived (instead, I had lived in New York for several years before starting to work on Manhattan Unfurled) to knowing all of its buildings that are visible from the Thames. Throughout the process, what I drew of the city of London became slowly engraved in my brain, sometimes even overwriting the visual imagery that I had been absorbing of the new city I had just moved to at that time (Turin, Italy).

The idea of reducing an entire city into miniature was turned upside down when I was commissioned to work on a drawing that would occupy a 120-meter long, five-storey high wall at JFK’s American Airlines Terminal. Skyline of the World is an imaginary skyline where seventy cities from around the world are intertwined. It’s an imaginary place where many famous landmarks are drawn side by side with anonymous locations from around the world; where all rules of proportions and perspective, of sequencing and concatenation are abandoned in order to replicate our idea of travel, rather than the actual places. A memory of a journey is a memory in which time and space blend. They both seem to vanish, as distances and places tend to be compressed into a single-yet-intense detailed blur. After a trip, the famous landmark you just visited will often be imprinted in your brain as much as the undistinguished building you saw from your hotel room window. Also, in memories, scale and perspective follow their own rules. Thus Skyline of the World is a drawing in which one city dissolves into the next without following a predictable course. The same city may appear in multiple places throughout the drawing, and the buildings in the foreground appear smaller at times than similar sized buildings in the background. What is in front does not necessarily obstruct what is behind.

Line drawing is a fantastic yet demanding technique. Just like writing, its narrative potential lies in each line’s ability to express as much information as possible by being in that precise location and not in any other.