L’Indice dei libri del mese

review by Francesco Gallo

review by Francesco Gallo

Matteo Pericoli

Il grande museo vivente dell’immaginazione

Guida all’esplorazione dell’architettura letteraria

168 pp, 25 €

Il Saggiatore, Milan 2022

January 30, 2023

Who knows where Italo Calvino would have placed a book like this: among the Books That Are Missing To Put Next To Others On The Shelf, or the Novelties Whose Author Or Topic Attract Us? We like to think that the author of If One Winter’s Night a Traveler would have placed The Great Living Museum of the Imagination among the Books That Inspire Sudden, Frantic And Not Clearly Justifiable Curiosity.

More than a book, in fact, it is a guidebook; a Guide to the Exploration of Literary Architecture. There are Maps (Ground Floor, First and Second Floor), a Legend of Spaces (Entrance, Rooms 1 and 2, and Inner Courtyard). And there is a guide, of course: the author himself – speaking in a voice that is not his, but ours (but we will understand this as we read on…). A guide who, instead of escorting us along a series of obligatory steps, as a first thing wants us to feel free; free to go where we please, observe what we please, and, most importantly, imagine what we please. He is quick to reiterate, in fact, that “museum” comes from “mūseóon,” meaning the place sacred to the daughters of Zeus where one could contemplate and imagine in full autonomy.

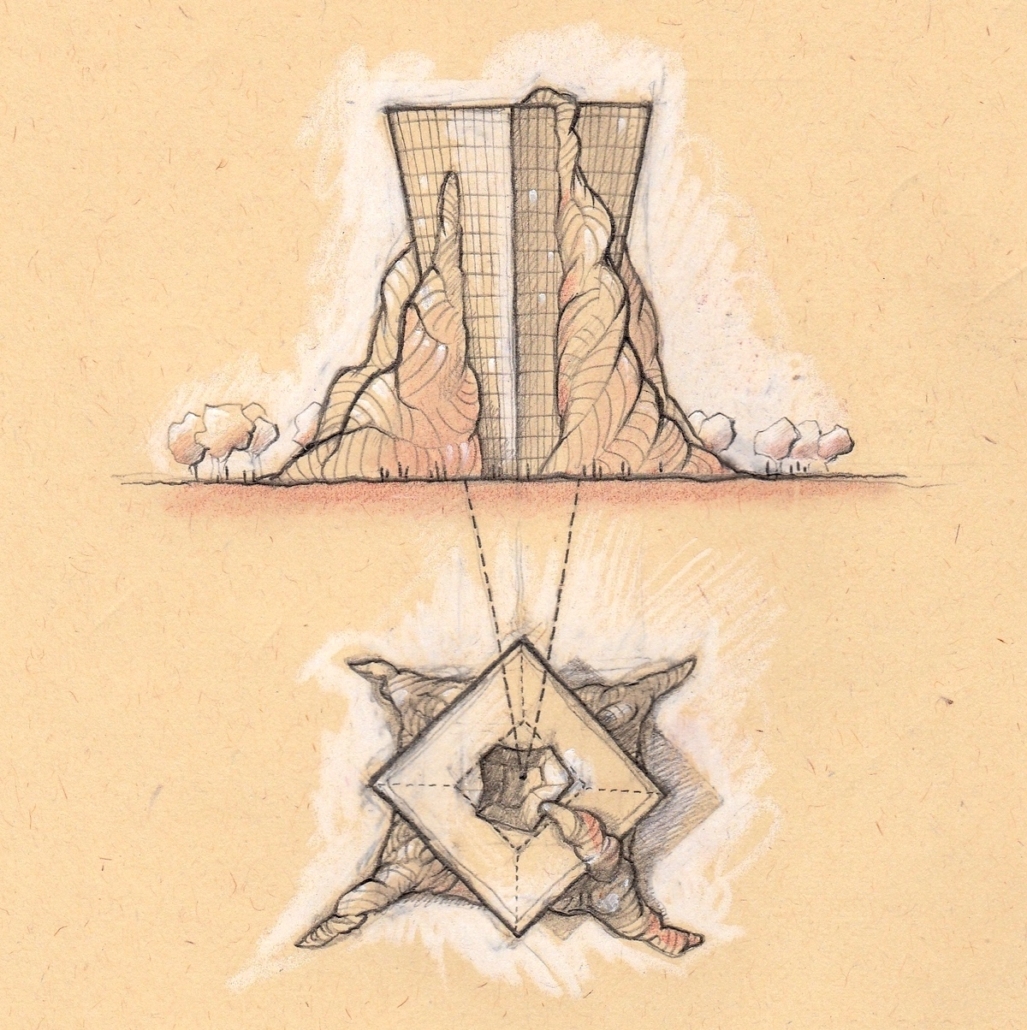

But what is literary architecture? It is an ongoing discovery. Not only that: an attempt to increase our awareness when we relate to spaces (and the void). More: a series of educational workshops that, over the past twelve years, architect, designer and author Matteo Pericoli has held around the world; from Turin (where it all began) to New York, via Dubai.

Inspired by the discovery of a lexicon common to both architecture and literature – how many times have we heard, about a story endowed with uncertain logical connections, that it “lacks structure,” “wobbles,” or “doesn’t stand up”? -, Pericoli has traversed the history of architecture as an attempt to narrate; at first simple, then increasingly complex.

What is the impulse that unites the first hut – when the basic idea was that of a “roof-over-the-head-so-I-don’t-get-wet” – to the first “house-with-a-window” – an “architectural element that connects what is tangible (the frame itself) with the intangible (the view, the outside) and thus the real with the imaginary, the everyday with the absolute” – if not a narrative impulse, the incipit of a story destined irrevocably to complicate itself?

Alice Munro writes: “A story is not like a road to follow … it’s more like a house. You go inside and stay there for a while, wandering back and forth and settling where you like and discovering how the room and corridors relate to each other, how the world outside is altered by being viewed from these windows.”

By stripping architecture of its least relevant elements – the style, the name of the person who designed a certain project, its historical value – Pericoli shows us the spot where the essential lurks; that which “can neither be touched (the space) nor read (the architecture of a story).” Removing the walls, ceilings, windows, etc., removing the envelope, in short, what is left but a void, the void? And setting aside the words, sentences, punctuation and paragraphs of writing a story, what is left but an essence that “can only be intuited and deduced,” as when we confront the ghostly voice of Kurtz in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, or try to intuit the subject matter of the dialogue between the girl and the American in Hemingway’s Hills Like White Elephants.

Having delved into these reflections from a theoretical point of view – Room 3 contains an enlightening lecture on creative writing; Room 4 reiterates the importance of reading as a wonder-generating activity -, Pericoli, with his characteristic lucidity and politeness, invites us on a tour of the Great Hall where it is possible to view no less than twelve interpretations of literary architecture. Then, a moment before the bookshop (unfailing: as in any museum), he gives us instructions for making our own literary architecture so as to display it in our own, very personal living museum of the imagination. (And reminds us, too, that in architecture it makes little sense to distinguish between “expert” and “non-expert” people, since we all experience our relationship with space.) The only rule in this game – because there are no games without rules – is to always maintain a literary approach, never a literal one. What are we to do with a model of a lighthouse if what we are actually excited about is the dense web of relationships that governs the behavioral dynamics of the Ramsay family during a famous trip to the Isle of Skye? Why not give it a try, then? In between reflections, we may be able to free ourselves “from the inevitable burden given by preconceptions and preclusions due to the judgments and interpretations of others,” and discover something new about the mysterious relationship between architecture and literature. And, why not, about ourselves.

https://www.lindiceonline.com/letture/matteo-pericoli-il-grande-museo-vivente-dellimmaginazione/