Very excited to be talking about the LabLitArch at Princeton University next week!

https://ams.princeton.edu/events/cosponsoring/mellon-forum-mapping

Very excited to be talking about the LabLitArch at Princeton University next week!

https://ams.princeton.edu/events/cosponsoring/mellon-forum-mapping

From the LabLitArch News page

From the LabLitArch News page

The first workshop was held in April, in collaboration with professor Marco Maggi of USI University of Lugano (CH), Institute of Italian Studies, and organized by the City of Lugano.

An array of participants, including USI literary students, graduate design students, and two selfless local architects (Flora and Michela), attended. Professor Maggi’s area of research, which focuses on the “mental space” of the reader, allowed for a more in-depth exploration of how a literary text “carves out” a space from within the mind of the reader.

While working with one of professor Maggi’s students who has been visually impaired since birth, we realized how her ability to deduce an architectural space (obviously only its interior since its exterior shape isn’t perceivable to her) is incredibly similar to how a reader perceives the “structure” of a literary text, where words function not so much as “building blocks”, but more as excavating toolsthat actively create space by subtracting material from a solid mass (imagine, for example, the city of Petra in Jordan). A story, in fact, is obviously un-knowable from the “outside” and it’s only once we’ve begun to penetrate it (by reading it) that we start to slowly create a perception about its “construction”.

For this edition we worked on texts by Hemingway, Delius, Tabucchi and A.M. Homes. Here is a short video on our 20+ hours of practically continuous work:

The second workshop was LabLitArch’s very first experiment with music. It was in fact called “Laboratory of Musical Architecture”. It was held in May, in collaboration with professor Andrea Malvano of the University of Turin’s Department of Humanities. Professor Malvano, who has degrees in both literature and music (piano), selected pieces by Bach, Schumann, Schoenberg and Glass. The participants, all trained musicians or music students, worked with two experienced LabLitArch architects (Michelle Vecchia and Alessio Lamarca) to produce five amazing models:

We applied the very same methodology and approach used in many Literary Architecture workshops, i.e. working mostly backwards in search of possible motivating and implicit original inclinations that were at the basis of the creation of the musical pieces. As with literary texts, we avoided manifesting what is somewhat already explicit in the music. By working in the opposite direction, so to speak, we tried to get as close as possible, if it is even ever attainable, to the composer’s original creative sparkor insight or intuition.

This led us to the realization that, in music as in literature, movement in this direction forces us to leave our familiar disciplinary turf and we end up reaching a kind of expansive narrative ground probably common to most human artistic endeavors. Perhaps there indeed exists a sudden creative impulse, which is neither made of words nor of notes — it’s just there, as a not-yet-manifest expression of a narrative intuition. If so, narrative is truly all-pervasive. And architecture, with its fundamental narrative elements such as volume, space, light, weight, revelations, suspension, etc. seems to be an ideal tool to analyze, explore and even enter this boundless space of narrative.

This led us to the realization that, in music as in literature, movement in this direction forces us to leave our familiar disciplinary turf and we end up reaching a kind of expansive narrative ground probably common to most human artistic endeavors. Perhaps there indeed exists a sudden creative impulse, which is neither made of words nor of notes — it’s just there, as a not-yet-manifest expression of a narrative intuition. If so, narrative is truly all-pervasive. And architecture, with its fundamental narrative elements such as volume, space, light, weight, revelations, suspension, etc. seems to be an ideal tool to analyze, explore and even enter this boundless space of narrative.

Insight from both of these workshops will hopefully be included in the Literary Architecture book I am working on with Il Saggiatore. Work is progressing well and, as an additional sneak preview, I would like to share this new sketch of the book’s structure, here. At first glance, it may not seem so different from the previous sketch; but to me, and my very-limited writing experience, it represents a huge step forward!

Check the original post from the LabLitArch website:

http://lablitarch.com/2019/06/lablitarch-news-two-illuminating-workshops/

di Marco Maggi

Arabeschi N. 12, Dicembre 2018

Con l’aria di disegnare architetture e profili di città, Matteo Pericoli conduce da vent’anni un’indagine profonda e affascinante sul senso dei luoghi e dell’abitare. L’autore stesso la definisce una «ricerca dello spazio attraverso il disegno del dettaglio».

All’origine fu Manhattan Unfurled (2001), lo skyline della City di New York srotolato su due nastri di carta della lunghezza di dodici metri ciascuno; quindi il rovesciamento di prospettiva con Manhattan Within (2003), la città vista dall’interno di Central Park. Seguirono London Unfurled (2011) e prima, in forma di ‘capriccio’, niente meno che World Unfurled (2008). Nel frattempo la sperimentazione sulla forma panoramatica era stata affiancata da una ricerca sulle ‘vedute’, con The City Out My Window: 63 Views on New York (2009).

Con l’inizio di questo decennio Matteo Pericoli ha orientato sempre più la sua ricerca sulle relazioni tra architettura e letteratura. Lo strumento d’indagine è sempre lo stesso, la sua matita, al più ora affiancata dai modelli in tre dimensioni costruiti nell’ambito di un Laboratorio di Architettura Letteraria proposto con successo nei dipartimenti di architettura e nei corsi di creative writing delle università di mezzo mondo, da Ferrara a Taipei, da Gerusalemme a New York.

Abbiamo incontrato Matteo Pericoli a margine dell’edizione del Laboratorio di Architettura Letteraria svoltasi alla Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo di Torino tra il 16 e il 19 novembre 2017.

D: Il Laboratorio di Architettura Letteraria si presenta come un’«esplorazione transdisciplinare di narrazione e spazio». I partecipanti sono invitati a costruire con colla e cartoncino un modello architettonico capace di restituire a un potenziale visitatore l’esperienza percettiva, cognitiva ed emotiva ricavata dalla lettura di un testo narrativo. Da quale percorso è nato questo progetto?

R: Volendo fingere di rendere in maniera lineare un percorso che è stato in realtà tortuoso e spezzato, costellato di sorprese e casualità più che guidato da un disegno consapevole, direi che all’origine fu la tesi di laurea in architettura con Volfango Frankl e Domenico Malagricci, che erano stati collaboratori di Mario Ridolfi. Lavorando con loro avevo avuto il sentore che l’architettura fosse qualcosa di diverso dalle cose che avevo ascoltato nei corsi universitari a Milano. Tra l’altro, loro, anche per ragioni anagrafiche, disegnavano tantissimo, facevano tutto a mano, in un momento in cui – si era all’inizio degli anni Novanta – si stava affermando la tendenza a fare tutto al computer.

Fu grazie a queste persone che mi venne la curiosità di andare a vedere le architetture dell’ultimo Michelucci, dalle quali compresi un principio che ho cercato poi di applicare all’architettura letteraria: l’intuizione, cioè, che il materiale da costruzione non sono tanto soffitti e pareti, bensì il vuoto; che l’architettura è in primo luogo modellazione dello spazio.

Fu su questa spinta che mi decisi ad andare a New York, dove finii per lavorare nello studio di Richard Meier (dove peraltro scoprii, con un certo sentimento di rivincita, che là si faceva tutto a mano!). Qui però mi accorsi anche che ciò che mi interessava veramente fare era narrare col disegno. Volevo esplorare la dimensione della linea, che è l’elemento grafico più vicino alla parola, alla narrazione, per provare a dare una forma all’affetto che provavo per quella città. New York Unfurled è nato così, poi sono venuti tutti gli altri.

Anche il fatto di dover parlare, pensare e leggere in un’altra lingua ha forse favorito quel processo di ‘sganciamento’ dal linguaggio che mi ha condotto ad apprezzare la lettura in maniera diversa, a partire dall’esperienza sinestetica di percepire altro oltre alle parole. Come quando, passeggiando in una piazza con qualcuno, anche se sei concentrato su ciò che stai raccontando, quando arrivi dall’altra parte ti sei formato un’idea di quel luogo.

D: Poi ti sei trasferito a Torino.

R: Nel 2009 iniziai a tenere un corso alla Scuola Holden intitolato La linea del racconto. Facevo disegnare agli allievi della scuola di scrittura la loro finestra, quindi chiedevo loro di descriverla con le parole. Mostravo loro le opere di Saul Steinberg per indicare il territorio di confine fra scritto e disegnato che volevo che esplorassero. L’anno dopo quelli della Scuola mi chiesero vagamente di fare ‘qualcosa di più’. Fu così che nacque l’idea dell’architettura letteraria. Vedevo tutti questi ragazzi che parlavano di architettura dei romanzi, di funzionamento delle storie, e volevo dire loro: «Io in teoria sono un architetto, o comunque un appassionato di questa cosa che è lo spazio: perché non mi fate vedere, invece di parlarne, come funziona la narrazione, perché non proviamo a capire insieme perché, come si dice, le storie stanno o non stanno in piedi?». Il primo laboratorio fu sconvolgente, erano tutti studenti di scrittura, dunque nessuno sapeva costruire un modellino, c’erano cartoni dappertutto, ma le idee erano così incredibilmente avanzate, sofisticate, erano idee che non mi ero nemmeno lontanamente sognato durante gli studi di architettura. Fu allora che intuii che l’architettura letteraria non era un’idea ma un possibile cammino di scoperta.

D: Quali contributi può portare il tuo laboratorio alla comprensione di che cos’è un testo letterario?

R: La cosa forse più interessante di un’operazione come questa è che accende la luce su cosa succede nella parte destra del cervello mentre leggiamo. Pensiamo alla lettura come a un’attività confinata nell’emisfero sinistro, quello del linguaggio, ma in realtà qualcosa succede anche dall’altra parte. Il laboratorio consente di gettare luce su questa zona in penombra. Però al tempo stesso vorrei che la ‘magia’ avvenisse in maniera non scientifica. All’inizio, dopo i sorprendenti risultati delle prime edizioni, ero stato io a chiedere a dei neuroscienziati che si occupavano della percezione dello spazio di aiutarmi a comprendere cosa accadeva nel laboratorio. Ora, pur continuando a leggere su questi argomenti, preferisco cercare risposte dal laboratorio stesso, che ripropongo sempre quasi identico, sia perché spero di riprodurre ogni volta la sorpresa della prima volta, sia per misurare eventuali scarti, che sono grandi elementi di apprendimento. Soprattutto, credo che le risposte più profonde, più ancora che dallo studiare o anche dal progettare le architetture letterarie, vengano dal disegnarle con la matita e realizzarle col cartone: lì si vede subito come funziona una storia, se sta o non sta in piedi…

D: L’unico precetto dell’Architettura Letteraria, come spieghi ai partecipanti al laboratorio, è di essere ‘letterari’ e non ‘letterali’. Cosa intendi dire?

R: Se ‘costruisci’ Gita al faro di Virginia Woolf e fai il modellino di un faro sei fuori strada. Hai usato quello che l’autrice ti ha suggerito e ti sei fermato lì. Ma cosa significa la gita al faro, cosa è successo prima, la morte della nonna, l’assenza, il motivo per cui tu vai al faro… Tutto questo è assente. Se il faro lo inserisci alla fine, perché è coerente con la costruzione, allora può funzionare; però ci deve essere tutto il resto… Nella Gita al faro il faro può essere una soluzione architettonica diversa, il faro può anche essere un buco.

D: Di recente hai esplorato un altro aspetto delle relazioni tra letteratura e spazialità, con l’illustrazione delle architetture d’invenzione di due classici della letteratura italiana: i mondi ultraterreni di Dante per un’edizione scolastica della Commedia commentata da Robert Hollander e le utopie urbane di Italo Calvino per una traduzione brasiliana delle Città invisibili. Ti sei cimentato anche con le immagini di copertina di alcuni libri. Quali lezioni hai tratto da quest’altra diramazione del tuo progetto di ricerca letteraria attraverso lo spazio e il disegno? Come declini, in questo caso, il tuo precetto di essere letterari e non letterali?

R: È una domanda buffa, perché, nel caso dell’illustrazione, il precetto di essere letterari e non letterali non vale. A mio parere l’illustrazione dev’essere un servizio al testo, è lui che ‘comanda’, quindi va fatta con dedizione e ‘altruismo’. È una cosa diversa dall’architettura letteraria. Sono, per così dire, due sport diversi: l’illustrazione è una specie di tiro al bersaglio, devi centrare l’obiettivo; l’architettura letteraria, invece, è come il tennis: l’obiettivo è rinviare la palla entro uno spazio che è delimitato, ma che al contempo offre soluzioni diverse. Nel caso di Dante e Calvino, ho cercato di sottolineare tutti i passi in cui era chiaramente descritto come funzionano le loro architetture. Di lì in poi ho dovuto cercare soluzioni a problemi architettonici che né Dante né Calvino avevano dovuto affrontare, in quanto le loro architetture sono fatte di parole e non di tratti. Erano comunque sempre soluzioni fornite a problemi ‘tecnici’.

D: L’ultima domanda è rivolta al lettore. Uno spiraglio sui ‘tuoi’ autori è offerto dalle Literary Architecture Series pubblicate su ‘Paris Daily Review’, ‘La Stampa’, ‘Pagina99’: in ordine sparso, Fenoglio, Faulkner, Dostoevskij, Tanizaki, Carrère, Ernaux, Conrad, Calvino, Vonnegut, Ferrante, Saer, Dürrenmatt… Quali sono i tuoi favoriti? E soprattutto, che tipo di lettore sei? Come ti poni di fronte a un’opera letteraria?

R: Tutte queste letture sono state in qualche modo sorprendenti. In realtà per sei anni avevo chiacchierato tanto ma non avevo fatto nulla, nel senso di costruire architetture letterarie. Poi il direttore de ‘La Stampa’, Maurizio Molinari, mi lanciò la sfida. La prima fu Gli anni di Annie Ernaux. La chiave di Tanizaki è un’architettura perfetta. Mattatoio n. 5 di Vonnegut è una lettura che tutti dovrebbero fare, non ha niente a che vedere con le etichette che gli hanno appiccicato, la fantascienza, l’umorismo… È uno sforzo immane condotto con una leggerezza inimmaginabile, per me è quasi eroico. Credo che sarei più pronto a ricostruire domani la cupola del Brunelleschi – con qualcuno che mi aiuta! – piuttosto che scrivere una cosa così.

Nel corso di questi anni la lettura è diventata per me una sorta di viaggio esplorativo. Mi faccio prendere per mano, se lo scrittore o la scrittrice lo vogliono, oppure mi affido al mio desiderio di esplorare la storia alla ricerca di sorprese narrative, spesso soffermandomi a osservare i dettagli, così essenziali nell’architettura come anche nella narrazione; alle volte mi trovo a gioire e godere di quello in cui mi imbatto, ogni tanto a intristirmi per le potenzialità mancate, o per dettagli progettati male.

Leggi direttamente dal sito di Arabeschi: http://www.arabeschi.it/architettura-letteraria-una-conversazione-con-matteo-pericoli-/

It’s finally here and it is so exciting to see the Laboratory of Literary Architecture in a major academic publication! The Routledge Companion on Architecture, Literature and The City, edited by Jonathan Charley, features a chapter on the LabLitArch, which includes a narrative on the genesis of the laboratory, images, project samples, the Literary Architecture series, as well as a dialogue between professors Carola Hilfrich and Jonathan Charley about the pedagogical implications of the LabLitArch.

Excerpts from the dialogue between professors Carola Hilfrich and Jonathan Charley:

“One of the valuable features of the LabLitArch project is that it seems to suggest a ludic alternative to a super-rationalized modern education system.”

“It sets up a process of playful experimentation … that has all the edginess, marginality, contingency, and frustration as well as the serious stakes in liberating our thought from habitual constraints.”

“Seeing the process at work felt like being in loophole of knowledge production; a place where participants, thrown out of the respective boxes of their home disciplines, move into a hybrid, interactive, and reconfigurable field.”

“I think of Matteo’s Laboratory as a unique environment for exploring the potential of … moments where literature and architecture, words and buildings and spaces, readability and inhabitability intertwine with humans.”

“Asking us to put our hands on works of literature by architecturally removing their verbal skins, the LabLitArch makes us grasp their actual texture rather than their form or meaning, so as to shape it, collaboratively, as a habitable space.”

“LabLitArch is perhaps most transformative for our thinking and doing at moments of counter-intuition, competing intuitions, mixed intuition, or intuitions that fail us; and that its emphasis on intuition, or gut feeling, includes loops through the whole body and its more intentional responses, as well as through the imagination and the environment.”

“Matteo’s Laboratory is itself a theory of intuition and failure. Intriguingly, its teaching method in collaboratively haptic creativity advances from the outset a non-subjectivist approach; and it does produce end-results, in the form of architectural projects.”

Details here:

https://www.routledge.com/The-Routledge-Companion-on-Architecture-Literature-and-The-City/Charley/p/book/9781472482730

And here:

http://lablitarch.com/2018/12/lablitarch-in-routledge-academic-anthology/

Matteo Pericoli: l’architettura delle storie

di Alessandra Garzoni

In onda: 2 luglio 2019 – ore 8:00

Architetto e disegnatore attivo in Europa e negli Stati Uniti, Matteo Pericoli si interroga da anni sul perché le storie “stanno in piedi”. L’Architettura Letteraria, pratica innovativa di cui si occupa, esplora lo spazio narrativo passando per la costruzione di modelli architettonici delle opere letterarie. Ospite venerdì 29 giugno 2018 al Long Lake Festival, Matteo Pericoli ha dialogato con il Professor Marco Maggi dell’USI. Alessandra Garzoni lo ha intervistato per noi in occasione della sua visita a Lugano.

Prague, March 29, 2018

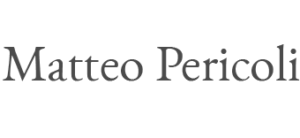

It’s a great honor to be part of Amnesty International’s “I WELCOME” campaign through this Art for Amnesty project exhibited at DOX Centre for Contemporary Art in Prague.

When I was asked to participate I wondered: “What do I do?”, “What do I welcome?”, “What have I learned from my predictable kind of work? I make drawings and I draw, among other things, what people see out their windows. So, what have I learned from doing this seemingly simple thing?”

I thought about it.

I thought I had learned about perspective.

I thought I had learned about expectations.

I thought I had learned about inspirations.

And, perhaps, I had learned about aspirations.

Window views, I thought, are metaphors of one’s journey through life. They are static, but they are also incredibly dynamic. I realized that they are also mirrors as they force us to reflect on ourselves and our lives.

So Art for Amnesty’s founder Bill Shipsey and I wondered, “What would we envision for a project like this?”

So Art for Amnesty’s founder Bill Shipsey and I wondered, “What would we envision for a project like this?”

And the answer was: “A magical, open window onto a world in which all places, those that today are privileged and self-centered — like me, like where I come from — are intertwined with those from which people are escaping.”

We are one, single, big thing on earth, and we all want happiness. But if we lived in a world that embodied what some politicians are proclaiming today, we would be living in a world made of walls with no windows, where we, the privileged, would also be living in darkness.

See the “I WELCOME” drawing here: https://matteopericoli.com/portfolio-item/i-welcome/[/av_one_full]

A newly edited LabLitArch video.

Special thanks to Twin Pixel Video and Al-Johara Beydoun (words).

Visit http://lablitarch.com/ for more information.

Italo Calvino

As cidades invisíveis com ilustrações de Matteo Pericoli Companhia Das Letras

Matteo Pericoli

On Invisible Cities

In Italy, if you study architecture (but not only), sooner or later you’ll end up having to read Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. It is usually among most design courses’ required readings — and rightly so.

When I had to read it, I felt what probably most architecture students feel: a sense of relief; the kind you breathe in when you walk out the door after spending hours in a crowded restaurant. Ah, some air, finally!

Finally architecture and cities that are alive, free from formal constraints, from styles or trends. And finally architecture that, although “only” told with words, conveys the energy and the idea that physical places need a narrative essence of their own.

As far as I was concerned, after that sense of relief, a sadness of sorts followed. Why — I wondered during my studies — do I feel the discipline of architecture so distant? So cerebral, rigid, and especially so hard to “understand”?

It took me a long time to come close to an answer. Or, rather than an answer, to a clarification of that very sense of relief that had struck me upon first reading the book. It’s now eight years since I’ve begun holding a workshop, the Laboratory of Literary Architecture, during which I work with students to give a tangible, architectural form to the intrinsic structure of novels, poems, and stories. They are all literary texts and there’s never anything explicitly “architectural” in them. We do not try to represent the locations described in the texts, but rather we try to understand — by actually building them with cardboard — the perceived reasons why a story works, why and how it stands, and the emotions it makes us feel.

For architecture students, it is a chance to get closer to narrative. If the participants are instead not architects — but writers, literary scholars, high-school students or simply readers — once the initial fear of the “for-experts-only” discipline (i.e. architecture) fades away, their spatial and design ideas evolve in a surprisingly rich and free way revealing how accustomed we all are to perceiving and understanding the structure of a novel and how expert — in the sense of experience (experiri) — we are at “reading” the space around us.

It was during the first workshop’s final student presentations that I again noticed that sense of freshness and pureness I hadn’t felt since my first reading of Invisible Cities. In translating a story into space, architecture comes to life. At some point of their creative process, spatial and literary narrative share a similar forma mentis, which isn’t made of bricks and concrete or words and syntax, but of essential compositional ideas.

When assigned to architecture students, Invisible Cities is mostly read, studied and used in a literal way, i.e. from an architectural point of view. Wouldn’t it be great if this wonderful book could also serve as inspiration to dive into narrative and discover how the effort of constructing a story closely resembles that of designing a building? What does a threshold, a step or a window represent from a narrative point of view? How do we “read” or anticipate space? What gives us a sense of continuity? And of ephemerality? How can I control the pace of revelations?

Alice Munro said that “a story is not like a road to follow … it’s more like a house” to explore. A house that, according to its proportions, room arrangement, and openings will alter both the reader/visitor as well as how we view the world outside. She adds that every time you return, the house “always contains more than you saw the last time. … It also has a sturdy sense of itself of being built out of its own necessity.”

Writing has been used forever to describe and analyze architecture. Architecture, too, can in turn be used as an analytic tool to explore narrative and discover those aspects that are unreachable only with words.

Leggi l’articolo originale in italiano su La Stampa:

https://www.lastampa.it/cultura/2017/06/07/news/costruire-una-storia-come-una-casa-ecco-la-lezione-delle-span-class-corsivo-citta-invisibili-span-1.34608333

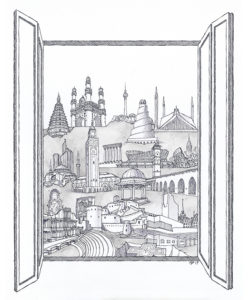

A journal kept from March 1, 2002 until February 24, 2003 that accompanies the 22-foot long accordion-format drawing in Manhattan Within (Random House, 2003)

[Clicca qui per la versione italiana]

In May 1998 I took my first Circle Line tour around the island of Manhattan. That three-hour-long experience was the inspiration for a book published in October 2001, Manhattan unfurled, that depicts the entire East Side and West Side of the island as seen from the water. In March 2002 I began working on a drawing of the city as seen from Central Park, looking out. The following text is based on the journal that I kept throughout the time I worked on that drawing, from beginning to end.

The time to put my hands and tools on the paper has finally come. The thirty-two-foot roll in front and ahead of me is white and scarily long. I have spent the last few months making sketches, taking photographs, trying one technique then another, always knowing that, so deep inside the island, the drawing cannot be just black and white, ink on paper. It has to have color; it has to seem to be made of matter. There isn’t simply water between the city and me—there is green this time, there are leaves, there is soil, there is dirt.

I have made some rough calculations: the park is 51 blocks long and approximately 10 street blocks wide, so its perimeter is about 122 blocks. This means that, for the drawing to fit on the thirty-two-foot-long roll of paper I have chosen, each block should measure three and a half inches, more or less. The rest will be improvisation. I don’t want the drawing to appear too scientific. What I am doing now is entering the park from its northwest corner, leaving the city’s noise behind—or, rather, all around—me. I am going in. I will then turn around and look back.

I have made some rough calculations: the park is 51 blocks long and approximately 10 street blocks wide, so its perimeter is about 122 blocks. This means that, for the drawing to fit on the thirty-two-foot-long roll of paper I have chosen, each block should measure three and a half inches, more or less. The rest will be improvisation. I don’t want the drawing to appear too scientific. What I am doing now is entering the park from its northwest corner, leaving the city’s noise behind—or, rather, all around—me. I am going in. I will then turn around and look back.

♠

Observed from the park, the city seems to rise from a cloud of trees. None of the buildings shows its base, its roots. Instead they all float upon the green cloud.

Outside the park, to locate yourself within the grid of the city, you need to know your coordinates—an avenue and a cross street. In the park, in order to understand where you are, you have to look outward, at the buildings.

The drawing will focus on the buildings that push in from just outside the park, and on the skyline that they carry on their shoulders. It will focus on a line, an imaginary and ever-changing line, created by the end of the park (at the tops of the trees) and the beginning of the city. The park in the drawing will fade away, since, for my purpose here, it serves only as a viewpoint from which to see the inner skyline of Manhattan.

♠

I have been searching for the missing pieces of the puzzle that I am trying to put together. Today I am working on a portion of Central Park North. The final look of the drawing will be a combination of what I have captured with photographs and what I have recorded in my sketchbook, all mixed with a good dose of invention. I will be drawing something that does not exist in reality or, better, that in reality is visible only piece by piece, never as a whole.

Walking around the park “in search” of the city is exactly what I feel this work should be: a hunt for a reversed, inside-out skyline. How the city reveals itself facing its center, its heart, within its inner edge, and not how the world outside sees it. And yet, while I was walking in the woods this morning, it suddenly occurred to me that I hadn’t entered the city more deeply but that I had just left it.

♠

Today I left the city and entered the park once again at 110th Street and Central Park West and walked along its edge all the way down to Sixty-sixth Street. I was inside the park but not too inside, jumping over stones and around trees to look at the city outside while hunting for an opening in the tree branches that would reveal a piece of the skyline to connect to the one I had just seen before.

The park itself would be nice enough on its own, but it is the backdrop of the city behind it that makes it magic. Most of the photographs of Central Park that I see people taking or that I have seen on postcards or collected in books about the city show the same thing: never the buildings alone, or the park by itself, but the juxtaposition, the contrast of the two together.

♠

All the photographs I need (dozens for each few blocks) and my notes are lying on my desk. It’s a mess. The thirty-two-foot-long piece of paper is rolled onto two wooden spools, one at each end. A two-foot portion is open right in front of me and ready to be worked on. The work I have already completed is rolled up on the left spool; the remainder of the drawing (thirty feet or so) is rolled up on the right one. Because I am right-handed, I move along the perimeter of the park clockwise. I have, somewhere in this mess, my regular basic graphite pencils (for the first rough sketch), my colored pencils, oil pastels, a steel point, and a set of harder, more precise, graphite pencils.

The many photographs spread out in front of me depict the portion of the skyline I plan to work on. They show different faces of the different buildings, from many possible viewpoints, in various seasons and light conditions. I begin by staring at these images for a long time. I need to absorb them and understand them. I have to isolate each building, learn how it relates to its neighbors, and discover its main characteristics or, rather, its character.

There is a moment during this phase when it seems the right time to make a first, rough sketch of the few blocks I am looking at. I sketch the buildings, their outlines and proportions, and choose a perspective from which to draw. It’s never right the first time—never. This sketch represents a series of possibilities: many lines cross each other, and the same building may show up in more than one place or in more than one position.

The most recently completed buildings (rolled up on my left) will help me determine the size of what will come next. Big buildings are tricky, since I risk overestimating their scale and finding myself later on with not enough vertical room on the paper.

Then I take my colored pencils and go over all the lines that I am interested in—all the lines that set those buildings in place and that portray their overall traits: height, width, depth, profile, but still no details, no patterns, no windows and such. I am fixing one outline among the many. The pencils are of various colors: blues, reds, deep yellows, oranges, violets, and variations of these. I use them at random, then I take the oil pastels and cover the whole sketch with a thick layer of soft colors: cream, azures, light yellows and oranges and white or off-whites. My hands get dirty with oil pastels, and the colored-pencil sketch disappears, almost completely buried by the oil. I can barely make out, if at all, the lines from the drawing below.

Then it’s time to take the fine steel point, a burin, and start to scratch away—searching for the lines that lie underneath. I find them, here and there, and what I find are not precise, straight, or univocal elements. They are confused lines, combinations of many scratches in many directions. It’s like excavating a buried city. Every line I find gives me a clue, a clue about the city to be discovered and a clue about my own drawing. Sometimes I remember what I did and go by memory; other times I wonder, “Where the hell did I put that line?”

This is the most exciting part of the process, during which I don’t know exactly what I am doing. I just search and react to what I see coming up in front of me. There is no way to make a mistake, since if I scratch where there is no line, I’ll just look elsewhere. The line, being the result of a series of tentative lines, is similar to the spirit of what I’d like to do: this skyline is not the skyline, the only possible skyline, but the result of many possible portions of a skyline that, as a whole, is invisible.

I keep scratching. Quietly, the drawing resurfaces. The city reemerges. It’s like archaeology. The city rises from the bottom of the paper and melts with the oil pastel.

After the buildings have reemerged, I take my more precise—much harder and very sharp—graphite pencils to give their shapes and volumes strength, and continue sculpting the forms by adding all the details, patterns, and windows. At this point I usually feel some nausea, for these buildings have an untold number of windows, openings, glass walls, etc.

After the nausea passes, I go back with the burin and scratch away the oil pastel from all the windows, so that they gain in depth. Finally, with a softer graphite pencil, I add an L-shaped line to two edges of all the windows that fixes and gives depth to the hole.

♠

Each of the four sides of Central Park shows a different face of the city. Imagine cutting a square out of the center of a cake and putting yourself inside that opening. Looking out at the four sides, you would see the inner layers of the cake, what they are made of, all the colors and textures of the different fillings, creams, jams, and so on. But you wouldn’t see any variation from one side to the other. Whereas in the park—and this is the big difference between the cake experiment and the Central Park experience—each side is unique.

Central Park was carved out from the city’s grid when very little had been built all around it. When the city expanded, and took over the island, that first cut was left intact. Now, looking south from inside the park, we see the immense power of the midtown structures pushing north; looking east and west we see elegant two-towered early-twentieth-century apartment buildings, Art Deco details, and museums; looking north we see Harlem, a gentle and architecturally softer part of the city, with buildings not too high, or so low at times that from the park you can’t even see them. They relate to the park in the most natural way, as a small town in the country would relate to its outskirts, to the cultivated fields. The long avenue blocks of Central Park North, with rows of town houses and hundreds of metal fire escapes reflecting the wide-open southern light, inspire a very different emotion than the opposite side, the architectural congestion of Central Park South, fifty-one blocks away. Rockefeller Center and the other skyscrapers from the dense midtown jungle push on the first row of buildings along Central Park South; they almost topple them. The swooping skyscraper behind the Plaza hotel seems to have been built so as to resist those pressing from behind.

♠

The first turn proves easier than I had expected. Of all the little lies that this drawing tells, turning the corner, rotating by 90 degrees from one side to the next, is probably the biggest. The corner has to be flattened in the drawing and cannot interrupt its continuity. Up here, at the corner of Central Park North and Fifth Avenue, the two identical apartment towers work perfectly as a pivot for the turning point: the space in between them is the void around which I will jump from looking north (at Central Park North) to looking east (at Fifth Avenue). The city in the back will follow; it will follow like the moving arm of a compass. The two vistas melt easily into one another and the corner opens up. Down at the two major corners, where Central Park South crosses Fifth Avenue or Central Park West, the city surrounds you like an amphitheater, its masses looming heavily above you.

♠

In the park again, taking photographs and making notes. Freezing cold, again, which luckily means no leaves on the trees yet, but also frozen extremities. Winter is the best time for views but the hardest for capturing them. My bulky gloves make it extremely hard to press the camera’s button and almost impossible to hold my pencil.

By now, I must have at least eight hundred photos, and I am starting to recognize the buildings, even buildings I haven’t drawn yet. Even so, I never feel I really know anything until I draw it. I wonder what we really see when we walk around, or even when we take pictures. I am always thinking about the moment when I’ll draw what I am photographing, because then, and for me only then, the moment of understanding, learning, and knowing will take place.

♠

Today I was looking at Central Park West, from the eastern edge of the Sheep Meadow, when a woman behind me said, “What a beautiful work of art.” I was struck by her comment because yes, it was an incredible view, but to what “work of art” was she referring? The park? The green of the meadow? A particular building? Who was the artist? Mr. Olmsted, who designed the park? Or the architects who designed the buildings along Central Park West? All of them, but certainly all of us, too. They who brought this to life, and we who love it.

There are unique places and extraordinary architectures everywhere, and they can be divided into two categories: places that are aware of their own beauty and places that are not. Manhattan belongs to the latter. Its beauty is raw, since what we love was not designed to merely please us but was designed for practical reasons. Imagine the grid system, the wild economy-driven urban development. Imagine the desire to go higher because of the cost of real estate, and the terracelike setbacks of the early-twentieth-century buildings determined by zoning regulations. All this resulted in what we see and appreciate today. (No one designed the winding roads of many Italian medieval towns to create charming views for tourists. A winding road follows better the topography of the area, creates a barrier to the harsh winter winds, and is easier to defend.) The park was the result of a fight won by ordinary people to ensure for themselves a very basic need: fresh air.

So you could say that the view is not a “work of art,” since there has been no single-handed decision behind it, but in fact it’s New York, the physical city itself, that makes such decisions with a life and mind of its own. Its structure and inner mechanisms have become the foundation for the automatic creation of works of art. It is difficult to make a mistake, since it is hard to ruin a system that absorbs almost anything, assimilates it, and gives it back to us as a part of itself.

I have trouble looking at and judging buildings in New York for themselves. Many are not nice, many are truly unpleasant, perhaps, but it would make sense to say so only if they were somewhere else, completely isolated. Here they don’t strike me as ugly. One cannot think of the skyline as simply the sum of its parts. The skyline is not the sum of its buildings against the sky. It is something over and above that—something that transcends the buildings and has a life of its own.

♠

In a few days the park will be filled with green. The birds will be back, and a thick layer of leaves will silence most of the city’s noise and obscure parts of the view. The city will step back. The views in the “green” period of the year show a city far away, more distant and more mysterious.

♠

The other day I was taking pictures from an apartment on the twelfth floor of a building on Fifth Avenue and Ninety-eighth Street. Staggering views, amazing apartments. I have visited more than a dozen of them. It worked like a chain: someone whose apartment I had recently visited would call a friend in another building and so on. Those who welcomed me seemed to share a similar perception of their views. Indeed, there was a sense of pride in the way they led me to the window, that in fact it was their view—not the world outside the window, but an extension of their apartment. An additional room. I could feel the city’s tangible presence in their lives. The photographs from all those apartments are essential to understand and organize the information I gathered from the park.

In addition, from high up I could see the mass of the city pressing onto the park far more clearly than from below. The transition from park to city is sudden and abrupt. There is no in-between. From so high above the tree line, the sea of green and the density of this city’s life come to touch each other yet never overlap, as if an invisible wall were standing there to separate them. Imagine an ancient city protecting itself not from the outside world but from something within itself. Imagine a city that built a rectangular wall, left the inside of the rectangle empty—because that’s the outer world—and built only around that wall. That would be quite an unusual city.

♠

I think that this is the real skyline of Manhattan. From the park all the buildings seem to look at me. When I was working on the skyline along the edge of the island, they were giving their backs to me as if they didn’t care.

♠

I remember when, just a few weeks after I moved to New York City, in December 1995, an enormous snowfall hit the area. Foot upon foot of snow fell within a few days. The city stopped, like a hiker who pauses to catch his breath and brush the snow off his shoulders.

The volumes, the shapes, the size of the constructions in the city were something I still had to get used to. Fresh from Italy, and from my architectural experience and studies over there, walking around buildings higher than ten stories, or underneath floating structures spanning more than fifty yards, required a complete readjustment of my senses. (A place is first grasped with the senses, and later explained or appreciated with heart and mind.) The noise and the smell of the city were just as new. An afternoon walk in midtown for somebody just off a plane is not an easy thing: yellow stains mark the rivers of cars with their color and honking, vapor is exhaled from holes in the ground, sunlight rarely makes it through the density and height of the buildings, whose tops are often invisible, since they are set back and are way too high to see. Construction and transformation are everywhere. Not one thing seems to stand still. All of these sensations overwhelmed my efforts, as a newcomer, to simply see, to understand this place. But luckily, as I said, one day (or, actually, one night) the snow came and with it a layer of silence settled on the city—the way my grandmother used to wave a cloth onto the table with a smooth one-shot motion before setting it for a meal. The snow placed itself uniformly all over the city, and quieted everything. Everything stopped—buses, subways, cars. I could walk anywhere, anytime. I could look up without fear of walking into somebody or being hit by a car. New perspectives opened up. My vision sharpened, like the vision of a driver who lowers the volume of the radio in order to pay attention to the road signs.

That silence was one of the most beautiful gifts the city offered me. That silence helped me. It helped me make all those big volumes, dimensions, proportions a little more mine, to give them a human shape. It helped me relate myself to them. I saw the Empire State Building, the canyons along Sixth Avenue in midtown, the unreachable tops of all those skyscrapers in a way they were never intended to be seen: tamed and quieted by nature, forced, like the rest of us, to wait for the storm to be over before they could resume their usual rhythm and power. There was no difference, in that moment, between them and me. The chaos that soon returned never took that memory away.

♠

A drawing is made of lines, lines are an abstraction of reality, and as such they are fictions. They must be invented time after time. The lines of a drawing are the result of a complex (although intuitive) series of decisions regarding reality, choices about how to show something that does not exist any more than the horizon does. A drawing carries within itself the words “here is what I think” rather than “here is what I see.”

Lines can be drawn in many ways, using many different techniques, yet each one carries a different meaning, an intention. Getting from one point to another seems to be the only purpose of a line. But there is much more to it than that: there is the “how.” The “how” a line is drawn reveals the depth, the knowledge, and the degree of abstraction that one wants to convey. With a line drawing I can accurately show the geometry of the bottle in front of me, but I could also try to do more: I could use my pencil to create a line that “feels” the curve of the bottle’s neck; I could treat differently the line that represents the cylinder versus the one for the mouth of the bottle; and half of the mouth’s round opening will be closer to me, so that line should convey that, too, and so on.

When you look at someone else’s drawing, you can follow the paths of the pen or the pencil, and track either the eye as it searched the world or the mind as it dug into imagination. To draw from life, or to redraw a drawing already made by someone else, engraves in your brain what you are looking at.

As in a text, one can be ambiguous, one can insinuate, or one can use too many lines or too many words to describe something when the same could be done with less, compressing the amount of information to a convincing minimum. Lightness and precision can be expressed by both a line and a sentence (not the precision of a ruler-made line, but the precision that comes from serving a purpose). A line drawn to generate the shape of a building humanizes a view, like a warm and intense description of how the sun hits a building at a certain time of day. Words can make you think, as lines can make you see, what you hadn’t imagined before.

♠

I spent my first days in Manhattan lamenting what most visitors must complain about: my neck ached all the time from trying to see the tops of the buildings, which seemed to have been designed to be observed from their own height, not mine. The most beautiful details were all up there, among the clouds. Before they were erected, each of these buildings once stood on some architect’s drafting table, and since in a drawing the bottom, middle, and top are all visible at the same time, it makes no difference whether your building is a hundred feet high or a thousand; you just change the scale. So from the very beginning I was always more interested in how the buildings here in Manhattan relate to the sky than in how they relate to the ground. Bewildered by the height and the beauty of the tops of these gigantic structures, I didn’t find what happened at their bases as exciting. Where I come from, what counts most is how a building springs from the ground, how it relates to a nearby piazza and to us, human beings. The great exceptions over there are the cupolas, hollow structures built to allow your soul to reach up to the sky and meant to be seen from afar. But in a cupola what counts most is the void inside, not the structure itself. Here, instead, what counts is the question, “What is the building itself going to do when it meets the sky?” It is a new kind of relationship, not between architecture and the city, or architecture and the people, or architecture and space, but between architecture and sky.

♠

This drawing is on a long roll of paper. To look at it, to go along with it, feels like unfolding a story. The beginning and the end belong to two different moments in time. They are far away both physically and chronologically. While I work, I can see neither the beginning (since it’s rolled up on my left) nor, obviously, the end (on my right). An imaginary line marks the progress of the work and separates what’s finished and ready to be printed from what does not yet exist. The scroll, in fact, is a series of finished sessions. After each one, I roll up some more paper and start again from zero: sketch with the pencil, add the colors, then the pastels, and so on. The new portions will be seamlessly connected to the previous ones, but each will be a new drawing for me, a new experience: new buildings to understand, new proportions, new discoveries. They represent the many chapters of a story, unfolding in time and space, leaving behind what’s already been told.

♠

If you want to understand an ancient European city—Rome, for example—you have to first sit down and probably read a few books. You have to start to dig and peel away layers of time to imagine “what it looked like when,” and then put them back, in order, layer after layer of history, destructions, constructions, good ideas, terrible ideas, one on top of the other. This way you’ll have a sense of why you are seeing what you are seeing. A huge challenge, and a beautiful one. In Manhattan, if you take away a few hundred years—just a few hundred years—you are left with nothing, an island in a calm bay of the ocean, with lots of trees and strong rocks sticking out here and there. You can’t start that way, no. Instead you have to use your own senses, absorb all that you can, and retain as much as possible. You have to explain the city to yourself from what you see, not only from what you know. Manhattan is the result of now, not of yesterday or even the day before yesterday. The Venice of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance comes to mind when I think of Manhattan today. Venice was then at the highest point of its development, of its cultural production, and of its loneliness—attached by nothing to the mainland and looking, all alone, toward other worlds.

♠

Manhattan challenged my expectations. While being struck by the scale of some buildings, I was reassured by the gentle design of others; I was amazed by the density of some areas and calmed by the openness of others. When I was thinking of being in the middle of the American city, I suddenly realized another way in which it felt more like being in a medieval town in Europe: this city still has clear borders, demarcations, and thresholds. Today most ancient cities have been swallowed up by their outskirts, suburbs, and peripheries; they have been suffocated by their own growth and thus have completely lost their thresholds. In approaching them—before reaching the oldest part, the center—you have to go through layers and layers of recent, less-recent, quasi-old, old, and older areas until you finally see (and feel) that you are going back in time. Time doesn’t work only vertically in these cases, as in archaeology (up, more recent; down, older), but horizontally, too.

How nice it is instead to know that you are entering a place, or that you are leaving it, or that you have just crossed a river, or jumped into a castle over one of its drawbridges, defensive and welcoming at the same time. This is what you feel when you visit those beautifully preserved medieval cities of Europe (so old and so remote that they look fake, having lost all the practical reasons for maintaining their original fabric). You see one of these cities standing alone in the landscape, you locate it from afar, and you tell yourself, “Ah, there it is!” (which is a very important thing—to recognize something from far away in order to prepare yourself for the encounter). You approach it, it comes closer, you start to notice details, you begin to identify a civil tower and a bell tower, the main church, perhaps a cathedral. An idea of what you may be going to see within its walls starts to build inside your head.

Well, Manhattan turns out to be the same. If you approach it from the mainland you see it from far, very far away. When you get closer, different parts of the city take shape; you recognize some of the buildings, which you use in order to reconstruct your own map of the city. Very little makes sense if it’s the first time. If it’s the fiftieth time, you start to feel you are home again. You know that you have to cross a bridge to get there, or dive under the water to reappear on the other side, and you also know that as the density increases, so will the energy, and—once you are in—the rest of the world will remain behind.

♠

There is another peculiar thing about Manhattan, or actually the peculiar thing: the very center, the geometric center of the island, which in all the big historic European cities is the oldest and most crowded part, in Manhattan is simply empty. It is empty because of an unusual choice made when the expansion and the rush of development were still possible to block. Probably that was the one and only chance this city ever had to carve such an immense rectangle out of its own grid, out of its own money-making body and mechanism, and block any kind of construction at its edges. I can’t imagine a more courageous and more farsighted choice in designing the expansion of a city. Today Central Park is another aspect of Manhattan’s uniqueness: You want to get out of the city? Go in. Walk inward, not outward, and you will find yourself in the country, with the city all around silently looking at you, like a polite dog that waits patiently outside a store for its owner to come back. Yes, that’s what the city does; it stops right there and says, “Sorry, I can’t get in, I’ll wait for you here, just go ahead.” When you walk inside the park, you always feel the presence of the city, its desire to know where you are, and vice versa. There is a sense of mutual and implied trust, a patient city waiting for your return.

From outside the island, either from the surrounding rivers or from the outer boroughs, one can’t imagine such a wide-open space contained within that mass of buildings. And vice versa: from inside the park the outer edge is invisible; it doesn’t exist. The city is like a doughnut, but the only way you can see the hole and the outer edge is if you look from above. They were not made to coexist in one field of perception and yet they complement each other perfectly.

Furthermore, historically the city has always turned its back on the water. The water was never seen as an escape, in fact quite the contrary: a place to escape from. The edge of the island contained services, activities, and a kind of life that were to be left at the margin. (Just think of Tudor City, an entire neighborhood built without windows facing the water, in order to avoid the view of the slaughterhouses along the East River.) For a way out, the city could look in the only other possible direction: toward the true open, the park. Right in its core, in its heart.

♠

I have just finished working on the Guggenheim Museum, meaning that I just passed Eighty-eighth Street and Fifth Avenue, heading south. It is the first major landmark building that I have drawn since I started this project.

Landmark buildings affect us in many ways. We know them because, for one reason or another, they have entered a communal book of images, of memories, like a family photo album. Each culture has its own book of family photographs, but there are some sites that belong to a “universal” book of family photos. New York has many entries in this book, and rightly so—some are singular buildings and others are vistas from a specific point of view. We react when we see one of these places or buildings because we recognize something. But recognizing is quite different from seeing. When we recognize, we grow blind, and our capacity to innocently enjoy what we see practically disappears. Knowing becomes an obstacle, not an advantage. When you look at the Guggenheim you cannot not recognize it. In this drawing my goal is to look at the Guggenheim (or at any other landmark, for that matter) and try not to recognize it—to look at it, and draw it in the same way as I look at and draw, for example, the building that is right across the street from the Guggenheim. That white apartment building is not mentioned in any tourist guidebook to New York (although it shows up in some photos of the museum), but in order to understand the emotions that the Guggenheim stirs, one has to include its surroundings, one has to get an idea of the environment that hosts it.

♠

Halfway into the drawing, I can no longer distinguish one individual session from the other. The amount of work, day after day, is starting to melt into one thing, one single product. The drawing itself is coming alive and it is giving me the freedom to make mistakes.

At the beginning of any project, when all possibilities are in front of you, a wrong turn at the first crossroad will lead you away from your goal. Once, whether by instinct or luck, you begin to choose the right paths (although you don’t know that those are the rights paths until later), the mistakes you make become absorbed and fixed by the mechanism that you have been creating day after day. I was much more anxious, and my hand was less secure, during the very first feet of the drawing, when a big mistake would have produced only a minor loss, since I could easily have started over. You are not fully conscious of this new freedom at first, until you feel as if you are walking along with somebody, and that somebody is your work.

♠

Some years ago I made a motorcycle trip to Tunisia with my friend Stefano. We left Italy planning to go as far south as we could, if possible to reach the Sahara desert. On our way, in the southern part of Tunisia, we came to the immense dried-up salt lake called Shott El Djerid and discussed whether to cross or go around it. The lake is bisected by a single, completely straight, and I mean straight, ninety-mile-long road, clearly drawn on a map with a ruler and built accordingly. We decided, naturally, to go across.

We stopped for gas and some food in a little town at the edge of the dried-up lake and then left it behind in midafternoon. Our minds were accustomed to European roads and distances, to certain changes in landscape, and to feeling that after a stretch of straight road usually comes a curve, a change, usually. Any trip was paced by variety, and not by the feeling that at some point of your journey you start to think, “This must be over sometime soon—it has to be over.” Distance is something subjective, not objective, and “a lot” or “a little” depends on what you are used to. But for hours the lunar landscape that we soon encountered never changed. The first several miles had an interesting taste. The possibility of turning around and going back was there, and it somehow reassured us. But soon minutes began to dilate, while the landscape remained immutable, fixed in front, around, and behind us. What was happening? The road never posed a challenge since, as clearly shown on the map, it had no bends or variations. Our desire to reach the other side became unreasonably pressing too soon, so that our crossing grew first slightly uncomfortable, and then truly difficult. During the early part of the crossing, our sense of place, of speed, of the space around us was very unfamiliar. Later, as more and more miles accumulated, it slowly became part of us. At some point we knew that we were close to or had just passed the halfway mark, so there was no sense in turning back. Instead of pushing ourselves to continue, we were now pulled by the end of the road ahead of us. Weight was replaced by lightness.

All around us was landscape, dusty and salty sand. Our shadows were getting longer and longer. Traveling by motorcycle means that between you and the surroundings there is nothing. You are the surroundings. We melted into the scene. Stefano’s bike, in front of me, was a fixed point of reference, not moving but standing completely still, with that weird waterlike mirror effect caused by the heat rising from the road.

As we neared the other side, the end of the crossing pulled us harder and harder. We wanted to go faster, but, at the same time, we began to wish the journey could last. We began to miss that state of suspended time even before it ended. By the time we reached the other side the daylight was almost gone. In the west, the mountains that surrounded the dried lake were dark blue against the sunset, while the mountains opposite the sinking sun were fiery red.

There is no such thing as a simple ninety-mile-long straight road. It is complex; it has a different flavor for every mile you go; it pushes you, it pulls you, it hypnotizes you, or it repels you.

♠

The only way to stick to my apparently objective plan (“just draw all the buildings that look upon the park”) is to be totally subjective. The perspectives change every few blocks; they move as we move along the perimeter of the park. The only way that two of these perspectives can be connected is by coming up with a little lie: I have to show two opposite sides of two adjacent buildings that one would never be able to see at the same time. Also, every building has a preferred side, a better viewpoint to be seen and understood (in this, buildings are very similar to people).

The series of lies needed to adjust the perspective and its viewpoints works as a mortar for the pieces of the drawing. It keeps them together; it makes them one whole thing.

♠

I am approaching Fifty-ninth Street. So far the viewpoint has traveled along Fifth Avenue, parallel to the façade of buildings that face the park. It has stopped every so often to allow the perspective to be centered on some of the streets, but it has proceeded fairly smoothly. Now, as I get closer to the southeast corner of the park, the viewpoint has to decelerate, then come to a stop and rotate at the same time, to ultimately face Central Park South. If I were to take the four sides of the park and then simply join them, I would ignore the city that I see when looking straight at the corner, and the density directly southeast and southwest of the park would be completely lost.

Once the viewpoint completes its rotation and faces Central Park South, it can progress westbound, toward Columbus Circle.

♠

The buildings on Central Park South, and the buildings behind them, all seem to want to jump into the drawing. It is difficult to decide which ones to draw and which ones to leave out. Because they call out, they wave at me from way back, “Hey! What about me? You don’t want to put me in the drawing? Are you serious?” They are all over the place.

Creating a perspective for this stretch is harder, much harder, than I imagined. The span of Central Park South is not very long, so it doesn’t make sense to keep changing the viewpoint. Doing that would also create too many empty spaces (the vacuums produced by the juncture of two viewpoints), and the impression made by the incredible mass of buildings would be lost. So the one and only viewpoint is placed in the center, between Sixth and Seventh avenues. From there, I will first look east and then west to create a single view of the three long Central Park South blocks.

♠

Architecture doesn’t stand still but moves. Architecture is not something that needs to be looked at in order to be perceived. It is dimly perceived by our senses all the time. When we go about our daily occupations, architecture moves all around us; buildings dance and rotate and bend and blend into one another. We perceive their size and their various sides in motion. We absorb all of this unconsciously, completely unaware that we are the ones standing still in a world of moving masses.

When we look at architecture intentionally, then it stands still. We look at the details, at proportions, colors, and patterns, and we reconstruct all of that in our brain because “we want to understand.” We transform a sensory experience into an intellectual one.

Buildings talk to us. They talk about emotions and memories. They tell us something of the time in which they were designed and built, of the materials that were used, and the choice of details, or absence of details. In New York almost every building we pass speaks its own language. And in the park, from the park, this relationship—the dialogue between our senses and the thousand languages of the city—is surprisingly clear. It is clear because we are just distant enough to hear all those voices blend into a single one.

♠

After the loudness of Central Park South, it is not easy to go back to a more balanced and quiet rhythm. The buildings along Central Park West breathe more; they have plenty of air and room around them. The two-towered buildings (the Century, the Majestic, the San Remo, The Eldorado) are spaced from one another and dominate the skyline. Many Art Deco buildings start calmly until they reach the fourteenth or fifteenth floor, and then (like the one at the corner of Sixty-sixth Street) they explode in a display of details and decorations; they become suddenly oversculpted castles of sand. The Majestic, with its vertical moldings, appears to be springing directly from the bedrock. Others (like the Dakota or The St. Urban) seem to come from other cities and other eras. These buildings don’t give the impression of being pushed by a heavy mass behind their backs. They don’t need to fight in order to be seen, or to enjoy the view; they just stand there, proudly, in front of the park.

♠

The city is to the park what a tornado is to its eye: there is no wind, no energy in the eye of a tornado, only around it. The centrifugal energy of the storm opens its center, the silence feels unreal, the sky is clear, the city stays out.

♠

The grid system is a most welcoming mechanism. When I moved to New York, it took me one day to learn how and how long it would take me to go anywhere. (Except downtown, of course, which made me feel at home in another way because of its narrow and bending streets.) The grid system lets you grasp the whole of Manhattan instantaneously. It allows you to locate point A and point B, then to connect them and estimate the distance, the time, and the physical effort to get from one to the other. The comprehension of a European city, instead, relies upon the knowledge of itineraries. Knowing the location of point A and point B is often not enough to visualize and estimate the actual transfer. You need to know a certain number of set itineraries that connect different areas of the city, so that within those areas you can search for the specific points.

♠

A few weeks just spent in Italy, going back to very familiar smells and views of ancient cities, and to time heavily accumulated on stones, walls, and buildings. A few weeks spent in Ascoli Piceno, my family’s hometown, where the city’s center is an old, dense agglomerate of buildings from Roman, medieval, and Renaissance times, which protect a beautiful piazza, an open space completely clad with the same travertine that every other building is made of. That piazza, called Piazza del Popolo, opens up in front of you while you walk, all of a sudden, and offers you an empty rectangular space, paved and surrounded by porticoes, by the medieval municipal building (Palazzo del Popolo), and by the side (not the front!) of the main basilica (San Francesco). It is spectacular and reassuring at the same time. In Ascoli, my thoughts quickly returned to Manhattan, and to its treasured opening, Central Park, where the paving is grass and the columns around it are trees and magnificent buildings, all different from one another, paced by the streets’ grid rhythm. They vary in height, material, weight, and character, but they all face the park, as if they were respectfully looking at the city’s main piazza.

♠

It seems that all of us who come to New York from somewhere else want to know it, and know it in our own particular way. We want to discover things that nobody has discovered before, or that were somehow overlooked. And we want to understand why it’s so beautiful, and powerful, and where its energy comes from. We (who came from elsewhere) seem to take a while before we adjust to the fact that a place in evolution rarely allows itself to be explained. It simply needs your life—your own energy—that then becomes part of the “energy of the city.”

The city’s complexity and richness are the signs of its continuous transformation: neighborhoods that move around and that change in a matter of a few years, buildings that are replaced and rebuilt constantly, with new ones coming up at every corner. It requires energy to keep up with the change. Forget about understanding why.

♠

It’s early fall. I am in the park. The sun has just gone beyond the horizon, in New Jersey, and its brightness is fading, little by little. During this ephemeral moment, my affection for the city is strongest. It’s during this transition that the city appears humane and vulnerable. The birds in the park are almost completely quiet; the windows of the buildings facing west (along Fifth Avenue) turn bright and shiny in the last seconds of natural light. The lights inside the buildings go on gradually, but you can’t tell if what you see is coming from artificial light or reflections, since the reflections, in this very instant, appear as bright as the lights inside. It’s as if the last sparks of natural light get trapped inside the buildings.

I turn toward the other side (Central Park West) and look at the buildings that face east: the sun behind them is gone, and all the colors of the sunset paint the contrast of their silhouette. The buildings seem engraved against the sky, completely volume-less . At the same time the interior lights are turned on, gradually, sparsely and randomly, but they don’t look as brilliant, because of the glaring effect of the background. These lights restore depth to the buildings.

A fresh wind rises from the park, and that fresh wind seems to be the breathing of all the volumes reacting to the approaching darkness by expanding and contracting.

♠

The radio warned us this morning that the snowstorm that is about to hit New York today is a very big one: it will cover one third of the United States. Its size is unusual for early December. A phenomenon of this kind usually occurs later, in January or February.

I was in the park earlier this morning enjoying the sight of the falling snow and listening to the sound—tic, tic, tic—that it makes when it hits the few remaining, hardened leaves. In the middle of the North Meadow, along its northern edge, I spot a guy walking in the bushes. After seeing me, he rushes out and asks me in a heavy accent (I think from either Australia or New Zealand, I am not sure): “Where is south?” To such a plain and simple question, I reply by sticking my arm out in the right direction, toward the stretch of Central Park South, slightly tilted toward the Plaza hotel. The guy thanks me and starts to walk, but after a couple of steps he stops and asks me (and this time the accent is so heavy that I have to ask him, with my accented English, to repeat what he has just said): “How do you get out of here? I mean, do you have to know every path of this place or is there another way?” I couldn’t believe that he was putting his finger on one of the things I had been pondering for the last months. I was ready to have a long philosophical discussion on the idea of actually being out of the city, instead of “trapped inside” as he had implied. His question clarified the paradox of how the park relates to the city: he had expected to enter a very famous park, whereas on the contrary he found himself outside of the city, and lost, as in a fairy tale. Especially today, when the only thing that could be seen of Manhattan was a vague gray outline of buildings against a milky-white sky and ground, all the same color. I liked that he was asking me how to “get out” of there when in reality he was hoping, clearly anxiously, to get “back into” the city. Instead of boring him with all of this, I simply told him that, yes, one way is to learn all the paths, but that the other way, easier in my opinion, is to always use the buildings around the park as a reference for your position.

♠

That scientific aspect that I wanted so much to avoid—well, I really avoided it. The tree line has gradually wandered toward the bottom of the paper, a fact that I notice only now that I have come to draw the second of the two towers that stand at the corner of Central Park West and Central Park North. I drew the one on the north side of the street at the very beginning of the drawing, and now I have to draw the one on the south side at the end. I wanted to make sure that this last building is placed on the paper at the same elevation. I unrolled the drawing to the beginning and took a piece of sketch paper to trace the first foot of the drawing. Then I rolled back the entire drawing to the end and overlapped it onto the sketch. Well, they don’t match. The end of the drawing is considerably lower than the beginning. I don’t have much room to fix it (five or six blocks), but luckily up here in the park there is the Great Hill. The Great Hill is quite high and obstructs most of the view of the lower town houses along Central Park West and 107th, 108th, and 109th streets. Using the hill, I can elevate the green base and place the last building, “Towers on the Park” (South), more or less where it should be, facing its twin brother across the street.

♠

I am a few inches away; the end of the drawing has arrived. I have looked forward to this for so long, but now I don’t really want to see it end. I can smell the wood of the right spool. On my left there is a thick roll of paper. It looks older now. It’s filled with colors, lines, details of all the buildings I have drawn.

♠

In order to draw the last corner, Central Park West and Central Park North, I need to use the very first pictures taken a year ago. I am looking at the same corner 32 feet, at least 620 buildings, and more than 35,800 windows later. As I unroll the drawing, buildings pass by. I see the many sessions that are now one, the seamless seams. I recall the many choices, such as which face of a building to show, how to turn a corner, or where to place a perspective. The end has brought me back to the beginning, but this last seam—the seam of time—will not be invisible. This corner is not the same place to me anymore.

March 1, 2002 – February 24, 2003

La Stampa Torino, 28 settembre 2017

di Ilaria Dotta

“Costruire una storia è come costruire una casa. Uno spazio in cui si può entrare e rientrare più volte, per scoprirlo sempre differente. A cambiare è lo sguardo, la percezione mutevole di chi prende in mano il libro e, dopo un’occhiata veloce alla copertina, si tuffa tra le righe della prima pagina. È come spalancare una porta, accettando di addentrarsi nella struttura costruita, più o meno consciamente, dallo scrittore. Di immergersi nello spazio letterario edificato da qualcun altro. Ma che forma hanno un romanzo di Calvino oppure di Dostoevskij? Una semplice capanna o magari un castello dalle linee sinuose illuminato da mille finestre, o ancora un labirinto dai muri spessi e senza il tetto. Trasformare in palazzi le grandi opere della letteratura è ciò che fa Matteo Pericoli […]”

Continua a leggere sul sito de La Stampa:

https://www.lastampa.it/torino/appuntamenti/2017/09/28/news/matteo-pericoli-l-architetto-letterario-1.34427945