di Marco Maggi

Arabeschi N. 12, Dicembre 2018

Con l’aria di disegnare architetture e profili di città, Matteo Pericoli conduce da vent’anni un’indagine profonda e affascinante sul senso dei luoghi e dell’abitare. L’autore stesso la definisce una «ricerca dello spazio attraverso il disegno del dettaglio».

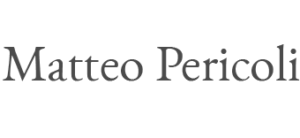

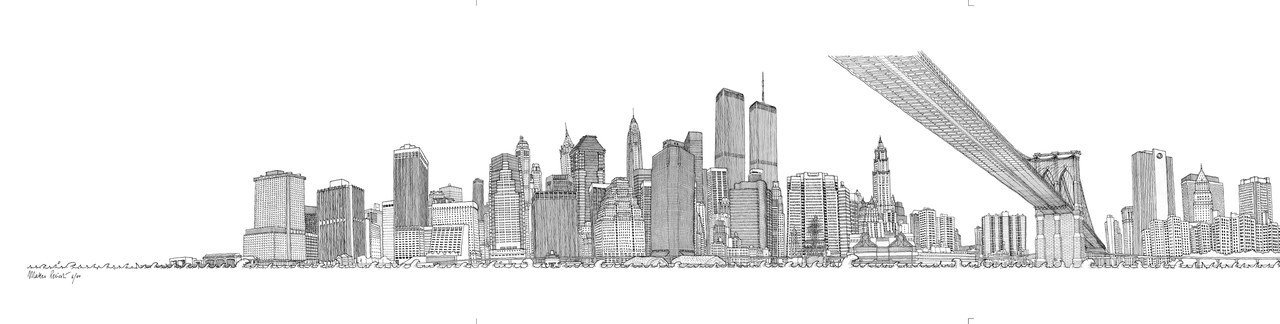

Manhattan Unfurled The East Side – Financial District (dettaglio)

All’origine fu Manhattan Unfurled (2001), lo skyline della City di New York srotolato su due nastri di carta della lunghezza di dodici metri ciascuno; quindi il rovesciamento di prospettiva con Manhattan Within (2003), la città vista dall’interno di Central Park. Seguirono London Unfurled (2011) e prima, in forma di ‘capriccio’, niente meno che World Unfurled (2008). Nel frattempo la sperimentazione sulla forma panoramatica era stata affiancata da una ricerca sulle ‘vedute’, con The City Out My Window: 63 Views on New York (2009).

Con l’inizio di questo decennio Matteo Pericoli ha orientato sempre più la sua ricerca sulle relazioni tra architettura e letteratura. Lo strumento d’indagine è sempre lo stesso, la sua matita, al più ora affiancata dai modelli in tre dimensioni costruiti nell’ambito di un Laboratorio di Architettura Letteraria proposto con successo nei dipartimenti di architettura e nei corsi di creative writing delle università di mezzo mondo, da Ferrara a Taipei, da Gerusalemme a New York.

Abbiamo incontrato Matteo Pericoli a margine dell’edizione del Laboratorio di Architettura Letteraria svoltasi alla Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo di Torino tra il 16 e il 19 novembre 2017.

D: Il Laboratorio di Architettura Letteraria si presenta come un’«esplorazione transdisciplinare di narrazione e spazio». I partecipanti sono invitati a costruire con colla e cartoncino un modello architettonico capace di restituire a un potenziale visitatore l’esperienza percettiva, cognitiva ed emotiva ricavata dalla lettura di un testo narrativo. Da quale percorso è nato questo progetto?

R: Volendo fingere di rendere in maniera lineare un percorso che è stato in realtà tortuoso e spezzato, costellato di sorprese e casualità più che guidato da un disegno consapevole, direi che all’origine fu la tesi di laurea in architettura con Volfango Frankl e Domenico Malagricci, che erano stati collaboratori di Mario Ridolfi. Lavorando con loro avevo avuto il sentore che l’architettura fosse qualcosa di diverso dalle cose che avevo ascoltato nei corsi universitari a Milano. Tra l’altro, loro, anche per ragioni anagrafiche, disegnavano tantissimo, facevano tutto a mano, in un momento in cui – si era all’inizio degli anni Novanta – si stava affermando la tendenza a fare tutto al computer.

Fu grazie a queste persone che mi venne la curiosità di andare a vedere le architetture dell’ultimo Michelucci, dalle quali compresi un principio che ho cercato poi di applicare all’architettura letteraria: l’intuizione, cioè, che il materiale da costruzione non sono tanto soffitti e pareti, bensì il vuoto; che l’architettura è in primo luogo modellazione dello spazio.

Fu su questa spinta che mi decisi ad andare a New York, dove finii per lavorare nello studio di Richard Meier (dove peraltro scoprii, con un certo sentimento di rivincita, che là si faceva tutto a mano!). Qui però mi accorsi anche che ciò che mi interessava veramente fare era narrare col disegno. Volevo esplorare la dimensione della linea, che è l’elemento grafico più vicino alla parola, alla narrazione, per provare a dare una forma all’affetto che provavo per quella città. New York Unfurled è nato così, poi sono venuti tutti gli altri.

Anche il fatto di dover parlare, pensare e leggere in un’altra lingua ha forse favorito quel processo di ‘sganciamento’ dal linguaggio che mi ha condotto ad apprezzare la lettura in maniera diversa, a partire dall’esperienza sinestetica di percepire altro oltre alle parole. Come quando, passeggiando in una piazza con qualcuno, anche se sei concentrato su ciò che stai raccontando, quando arrivi dall’altra parte ti sei formato un’idea di quel luogo.

D: Poi ti sei trasferito a Torino.

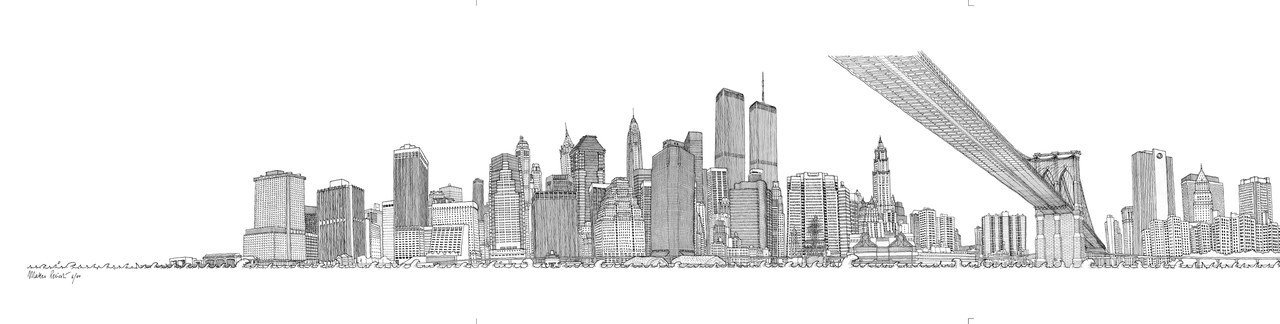

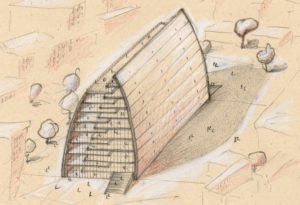

LabLitArch – Jeffrey Eugenides ‘Middlesex’

R: Nel 2009 iniziai a tenere un corso alla Scuola Holden intitolato La linea del racconto. Facevo disegnare agli allievi della scuola di scrittura la loro finestra, quindi chiedevo loro di descriverla con le parole. Mostravo loro le opere di Saul Steinberg per indicare il territorio di confine fra scritto e disegnato che volevo che esplorassero. L’anno dopo quelli della Scuola mi chiesero vagamente di fare ‘qualcosa di più’. Fu così che nacque l’idea dell’architettura letteraria. Vedevo tutti questi ragazzi che parlavano di architettura dei romanzi, di funzionamento delle storie, e volevo dire loro: «Io in teoria sono un architetto, o comunque un appassionato di questa cosa che è lo spazio: perché non mi fate vedere, invece di parlarne, come funziona la narrazione, perché non proviamo a capire insieme perché, come si dice, le storie stanno o non stanno in piedi?». Il primo laboratorio fu sconvolgente, erano tutti studenti di scrittura, dunque nessuno sapeva costruire un modellino, c’erano cartoni dappertutto, ma le idee erano così incredibilmente avanzate, sofisticate, erano idee che non mi ero nemmeno lontanamente sognato durante gli studi di architettura. Fu allora che intuii che l’architettura letteraria non era un’idea ma un possibile cammino di scoperta.

D: Quali contributi può portare il tuo laboratorio alla comprensione di che cos’è un testo letterario?

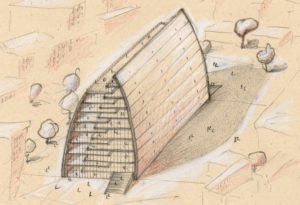

LabLitArch a Gerusalemme

R: La cosa forse più interessante di un’operazione come questa è che accende la luce su cosa succede nella parte destra del cervello mentre leggiamo. Pensiamo alla lettura come a un’attività confinata nell’emisfero sinistro, quello del linguaggio, ma in realtà qualcosa succede anche dall’altra parte. Il laboratorio consente di gettare luce su questa zona in penombra. Però al tempo stesso vorrei che la ‘magia’ avvenisse in maniera non scientifica. All’inizio, dopo i sorprendenti risultati delle prime edizioni, ero stato io a chiedere a dei neuroscienziati che si occupavano della percezione dello spazio di aiutarmi a comprendere cosa accadeva nel laboratorio. Ora, pur continuando a leggere su questi argomenti, preferisco cercare risposte dal laboratorio stesso, che ripropongo sempre quasi identico, sia perché spero di riprodurre ogni volta la sorpresa della prima volta, sia per misurare eventuali scarti, che sono grandi elementi di apprendimento. Soprattutto, credo che le risposte più profonde, più ancora che dallo studiare o anche dal progettare le architetture letterarie, vengano dal disegnarle con la matita e realizzarle col cartone: lì si vede subito come funziona una storia, se sta o non sta in piedi…

D: L’unico precetto dell’Architettura Letteraria, come spieghi ai partecipanti al laboratorio, è di essere ‘letterari’ e non ‘letterali’. Cosa intendi dire?

R: Se ‘costruisci’ Gita al faro di Virginia Woolf e fai il modellino di un faro sei fuori strada. Hai usato quello che l’autrice ti ha suggerito e ti sei fermato lì. Ma cosa significa la gita al faro, cosa è successo prima, la morte della nonna, l’assenza, il motivo per cui tu vai al faro… Tutto questo è assente. Se il faro lo inserisci alla fine, perché è coerente con la costruzione, allora può funzionare; però ci deve essere tutto il resto… Nella Gita al faro il faro può essere una soluzione architettonica diversa, il faro può anche essere un buco.

D: Di recente hai esplorato un altro aspetto delle relazioni tra letteratura e spazialità, con l’illustrazione delle architetture d’invenzione di due classici della letteratura italiana: i mondi ultraterreni di Dante per un’edizione scolastica della Commedia commentata da Robert Hollander e le utopie urbane di Italo Calvino per una traduzione brasiliana delle Città invisibili. Ti sei cimentato anche con le immagini di copertina di alcuni libri. Quali lezioni hai tratto da quest’altra diramazione del tuo progetto di ricerca letteraria attraverso lo spazio e il disegno? Come declini, in questo caso, il tuo precetto di essere letterari e non letterali?

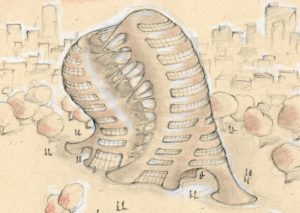

Zemrude

R: È una domanda buffa, perché, nel caso dell’illustrazione, il precetto di essere letterari e non letterali non vale. A mio parere l’illustrazione dev’essere un servizio al testo, è lui che ‘comanda’, quindi va fatta con dedizione e ‘altruismo’. È una cosa diversa dall’architettura letteraria. Sono, per così dire, due sport diversi: l’illustrazione è una specie di tiro al bersaglio, devi centrare l’obiettivo; l’architettura letteraria, invece, è come il tennis: l’obiettivo è rinviare la palla entro uno spazio che è delimitato, ma che al contempo offre soluzioni diverse. Nel caso di Dante e Calvino, ho cercato di sottolineare tutti i passi in cui era chiaramente descritto come funzionano le loro architetture. Di lì in poi ho dovuto cercare soluzioni a problemi architettonici che né Dante né Calvino avevano dovuto affrontare, in quanto le loro architetture sono fatte di parole e non di tratti. Erano comunque sempre soluzioni fornite a problemi ‘tecnici’.

D: L’ultima domanda è rivolta al lettore. Uno spiraglio sui ‘tuoi’ autori è offerto dalle Literary Architecture Series pubblicate su ‘Paris Daily Review’, ‘La Stampa’, ‘Pagina99’: in ordine sparso, Fenoglio, Faulkner, Dostoevskij, Tanizaki, Carrère, Ernaux, Conrad, Calvino, Vonnegut, Ferrante, Saer, Dürrenmatt… Quali sono i tuoi favoriti? E soprattutto, che tipo di lettore sei? Come ti poni di fronte a un’opera letteraria?

Tanizaki, La chiave

R: Tutte queste letture sono state in qualche modo sorprendenti. In realtà per sei anni avevo chiacchierato tanto ma non avevo fatto nulla, nel senso di costruire architetture letterarie. Poi il direttore de ‘La Stampa’, Maurizio Molinari, mi lanciò la sfida. La prima fu Gli anni di Annie Ernaux. La chiave di Tanizaki è un’architettura perfetta. Mattatoio n. 5 di Vonnegut è una lettura che tutti dovrebbero fare, non ha niente a che vedere con le etichette che gli hanno appiccicato, la fantascienza, l’umorismo… È uno sforzo immane condotto con una leggerezza inimmaginabile, per me è quasi eroico. Credo che sarei più pronto a ricostruire domani la cupola del Brunelleschi – con qualcuno che mi aiuta! – piuttosto che scrivere una cosa così.

Nel corso di questi anni la lettura è diventata per me una sorta di viaggio esplorativo. Mi faccio prendere per mano, se lo scrittore o la scrittrice lo vogliono, oppure mi affido al mio desiderio di esplorare la storia alla ricerca di sorprese narrative, spesso soffermandomi a osservare i dettagli, così essenziali nell’architettura come anche nella narrazione; alle volte mi trovo a gioire e godere di quello in cui mi imbatto, ogni tanto a intristirmi per le potenzialità mancate, o per dettagli progettati male.

Leggi direttamente dal sito di Arabeschi: http://www.arabeschi.it/architettura-letteraria-una-conversazione-con-matteo-pericoli-/