Very excited to be talking about the LabLitArch at Princeton University next week!

https://ams.princeton.edu/events/cosponsoring/mellon-forum-mapping

Very excited to be talking about the LabLitArch at Princeton University next week!

https://ams.princeton.edu/events/cosponsoring/mellon-forum-mapping

From the LabLitArch News page

From the LabLitArch News page

The first workshop was held in April, in collaboration with professor Marco Maggi of USI University of Lugano (CH), Institute of Italian Studies, and organized by the City of Lugano.

An array of participants, including USI literary students, graduate design students, and two selfless local architects (Flora and Michela), attended. Professor Maggi’s area of research, which focuses on the “mental space” of the reader, allowed for a more in-depth exploration of how a literary text “carves out” a space from within the mind of the reader.

While working with one of professor Maggi’s students who has been visually impaired since birth, we realized how her ability to deduce an architectural space (obviously only its interior since its exterior shape isn’t perceivable to her) is incredibly similar to how a reader perceives the “structure” of a literary text, where words function not so much as “building blocks”, but more as excavating toolsthat actively create space by subtracting material from a solid mass (imagine, for example, the city of Petra in Jordan). A story, in fact, is obviously un-knowable from the “outside” and it’s only once we’ve begun to penetrate it (by reading it) that we start to slowly create a perception about its “construction”.

For this edition we worked on texts by Hemingway, Delius, Tabucchi and A.M. Homes. Here is a short video on our 20+ hours of practically continuous work:

The second workshop was LabLitArch’s very first experiment with music. It was in fact called “Laboratory of Musical Architecture”. It was held in May, in collaboration with professor Andrea Malvano of the University of Turin’s Department of Humanities. Professor Malvano, who has degrees in both literature and music (piano), selected pieces by Bach, Schumann, Schoenberg and Glass. The participants, all trained musicians or music students, worked with two experienced LabLitArch architects (Michelle Vecchia and Alessio Lamarca) to produce five amazing models:

We applied the very same methodology and approach used in many Literary Architecture workshops, i.e. working mostly backwards in search of possible motivating and implicit original inclinations that were at the basis of the creation of the musical pieces. As with literary texts, we avoided manifesting what is somewhat already explicit in the music. By working in the opposite direction, so to speak, we tried to get as close as possible, if it is even ever attainable, to the composer’s original creative sparkor insight or intuition.

This led us to the realization that, in music as in literature, movement in this direction forces us to leave our familiar disciplinary turf and we end up reaching a kind of expansive narrative ground probably common to most human artistic endeavors. Perhaps there indeed exists a sudden creative impulse, which is neither made of words nor of notes — it’s just there, as a not-yet-manifest expression of a narrative intuition. If so, narrative is truly all-pervasive. And architecture, with its fundamental narrative elements such as volume, space, light, weight, revelations, suspension, etc. seems to be an ideal tool to analyze, explore and even enter this boundless space of narrative.

This led us to the realization that, in music as in literature, movement in this direction forces us to leave our familiar disciplinary turf and we end up reaching a kind of expansive narrative ground probably common to most human artistic endeavors. Perhaps there indeed exists a sudden creative impulse, which is neither made of words nor of notes — it’s just there, as a not-yet-manifest expression of a narrative intuition. If so, narrative is truly all-pervasive. And architecture, with its fundamental narrative elements such as volume, space, light, weight, revelations, suspension, etc. seems to be an ideal tool to analyze, explore and even enter this boundless space of narrative.

Insight from both of these workshops will hopefully be included in the Literary Architecture book I am working on with Il Saggiatore. Work is progressing well and, as an additional sneak preview, I would like to share this new sketch of the book’s structure, here. At first glance, it may not seem so different from the previous sketch; but to me, and my very-limited writing experience, it represents a huge step forward!

Check the original post from the LabLitArch website:

http://lablitarch.com/2019/06/lablitarch-news-two-illuminating-workshops/

di Marco Maggi

Arabeschi N. 12, Dicembre 2018

Con l’aria di disegnare architetture e profili di città, Matteo Pericoli conduce da vent’anni un’indagine profonda e affascinante sul senso dei luoghi e dell’abitare. L’autore stesso la definisce una «ricerca dello spazio attraverso il disegno del dettaglio».

All’origine fu Manhattan Unfurled (2001), lo skyline della City di New York srotolato su due nastri di carta della lunghezza di dodici metri ciascuno; quindi il rovesciamento di prospettiva con Manhattan Within (2003), la città vista dall’interno di Central Park. Seguirono London Unfurled (2011) e prima, in forma di ‘capriccio’, niente meno che World Unfurled (2008). Nel frattempo la sperimentazione sulla forma panoramatica era stata affiancata da una ricerca sulle ‘vedute’, con The City Out My Window: 63 Views on New York (2009).

Con l’inizio di questo decennio Matteo Pericoli ha orientato sempre più la sua ricerca sulle relazioni tra architettura e letteratura. Lo strumento d’indagine è sempre lo stesso, la sua matita, al più ora affiancata dai modelli in tre dimensioni costruiti nell’ambito di un Laboratorio di Architettura Letteraria proposto con successo nei dipartimenti di architettura e nei corsi di creative writing delle università di mezzo mondo, da Ferrara a Taipei, da Gerusalemme a New York.

Abbiamo incontrato Matteo Pericoli a margine dell’edizione del Laboratorio di Architettura Letteraria svoltasi alla Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo di Torino tra il 16 e il 19 novembre 2017.

D: Il Laboratorio di Architettura Letteraria si presenta come un’«esplorazione transdisciplinare di narrazione e spazio». I partecipanti sono invitati a costruire con colla e cartoncino un modello architettonico capace di restituire a un potenziale visitatore l’esperienza percettiva, cognitiva ed emotiva ricavata dalla lettura di un testo narrativo. Da quale percorso è nato questo progetto?

R: Volendo fingere di rendere in maniera lineare un percorso che è stato in realtà tortuoso e spezzato, costellato di sorprese e casualità più che guidato da un disegno consapevole, direi che all’origine fu la tesi di laurea in architettura con Volfango Frankl e Domenico Malagricci, che erano stati collaboratori di Mario Ridolfi. Lavorando con loro avevo avuto il sentore che l’architettura fosse qualcosa di diverso dalle cose che avevo ascoltato nei corsi universitari a Milano. Tra l’altro, loro, anche per ragioni anagrafiche, disegnavano tantissimo, facevano tutto a mano, in un momento in cui – si era all’inizio degli anni Novanta – si stava affermando la tendenza a fare tutto al computer.

Fu grazie a queste persone che mi venne la curiosità di andare a vedere le architetture dell’ultimo Michelucci, dalle quali compresi un principio che ho cercato poi di applicare all’architettura letteraria: l’intuizione, cioè, che il materiale da costruzione non sono tanto soffitti e pareti, bensì il vuoto; che l’architettura è in primo luogo modellazione dello spazio.

Fu su questa spinta che mi decisi ad andare a New York, dove finii per lavorare nello studio di Richard Meier (dove peraltro scoprii, con un certo sentimento di rivincita, che là si faceva tutto a mano!). Qui però mi accorsi anche che ciò che mi interessava veramente fare era narrare col disegno. Volevo esplorare la dimensione della linea, che è l’elemento grafico più vicino alla parola, alla narrazione, per provare a dare una forma all’affetto che provavo per quella città. New York Unfurled è nato così, poi sono venuti tutti gli altri.

Anche il fatto di dover parlare, pensare e leggere in un’altra lingua ha forse favorito quel processo di ‘sganciamento’ dal linguaggio che mi ha condotto ad apprezzare la lettura in maniera diversa, a partire dall’esperienza sinestetica di percepire altro oltre alle parole. Come quando, passeggiando in una piazza con qualcuno, anche se sei concentrato su ciò che stai raccontando, quando arrivi dall’altra parte ti sei formato un’idea di quel luogo.

D: Poi ti sei trasferito a Torino.

R: Nel 2009 iniziai a tenere un corso alla Scuola Holden intitolato La linea del racconto. Facevo disegnare agli allievi della scuola di scrittura la loro finestra, quindi chiedevo loro di descriverla con le parole. Mostravo loro le opere di Saul Steinberg per indicare il territorio di confine fra scritto e disegnato che volevo che esplorassero. L’anno dopo quelli della Scuola mi chiesero vagamente di fare ‘qualcosa di più’. Fu così che nacque l’idea dell’architettura letteraria. Vedevo tutti questi ragazzi che parlavano di architettura dei romanzi, di funzionamento delle storie, e volevo dire loro: «Io in teoria sono un architetto, o comunque un appassionato di questa cosa che è lo spazio: perché non mi fate vedere, invece di parlarne, come funziona la narrazione, perché non proviamo a capire insieme perché, come si dice, le storie stanno o non stanno in piedi?». Il primo laboratorio fu sconvolgente, erano tutti studenti di scrittura, dunque nessuno sapeva costruire un modellino, c’erano cartoni dappertutto, ma le idee erano così incredibilmente avanzate, sofisticate, erano idee che non mi ero nemmeno lontanamente sognato durante gli studi di architettura. Fu allora che intuii che l’architettura letteraria non era un’idea ma un possibile cammino di scoperta.

D: Quali contributi può portare il tuo laboratorio alla comprensione di che cos’è un testo letterario?

R: La cosa forse più interessante di un’operazione come questa è che accende la luce su cosa succede nella parte destra del cervello mentre leggiamo. Pensiamo alla lettura come a un’attività confinata nell’emisfero sinistro, quello del linguaggio, ma in realtà qualcosa succede anche dall’altra parte. Il laboratorio consente di gettare luce su questa zona in penombra. Però al tempo stesso vorrei che la ‘magia’ avvenisse in maniera non scientifica. All’inizio, dopo i sorprendenti risultati delle prime edizioni, ero stato io a chiedere a dei neuroscienziati che si occupavano della percezione dello spazio di aiutarmi a comprendere cosa accadeva nel laboratorio. Ora, pur continuando a leggere su questi argomenti, preferisco cercare risposte dal laboratorio stesso, che ripropongo sempre quasi identico, sia perché spero di riprodurre ogni volta la sorpresa della prima volta, sia per misurare eventuali scarti, che sono grandi elementi di apprendimento. Soprattutto, credo che le risposte più profonde, più ancora che dallo studiare o anche dal progettare le architetture letterarie, vengano dal disegnarle con la matita e realizzarle col cartone: lì si vede subito come funziona una storia, se sta o non sta in piedi…

D: L’unico precetto dell’Architettura Letteraria, come spieghi ai partecipanti al laboratorio, è di essere ‘letterari’ e non ‘letterali’. Cosa intendi dire?

R: Se ‘costruisci’ Gita al faro di Virginia Woolf e fai il modellino di un faro sei fuori strada. Hai usato quello che l’autrice ti ha suggerito e ti sei fermato lì. Ma cosa significa la gita al faro, cosa è successo prima, la morte della nonna, l’assenza, il motivo per cui tu vai al faro… Tutto questo è assente. Se il faro lo inserisci alla fine, perché è coerente con la costruzione, allora può funzionare; però ci deve essere tutto il resto… Nella Gita al faro il faro può essere una soluzione architettonica diversa, il faro può anche essere un buco.

D: Di recente hai esplorato un altro aspetto delle relazioni tra letteratura e spazialità, con l’illustrazione delle architetture d’invenzione di due classici della letteratura italiana: i mondi ultraterreni di Dante per un’edizione scolastica della Commedia commentata da Robert Hollander e le utopie urbane di Italo Calvino per una traduzione brasiliana delle Città invisibili. Ti sei cimentato anche con le immagini di copertina di alcuni libri. Quali lezioni hai tratto da quest’altra diramazione del tuo progetto di ricerca letteraria attraverso lo spazio e il disegno? Come declini, in questo caso, il tuo precetto di essere letterari e non letterali?

R: È una domanda buffa, perché, nel caso dell’illustrazione, il precetto di essere letterari e non letterali non vale. A mio parere l’illustrazione dev’essere un servizio al testo, è lui che ‘comanda’, quindi va fatta con dedizione e ‘altruismo’. È una cosa diversa dall’architettura letteraria. Sono, per così dire, due sport diversi: l’illustrazione è una specie di tiro al bersaglio, devi centrare l’obiettivo; l’architettura letteraria, invece, è come il tennis: l’obiettivo è rinviare la palla entro uno spazio che è delimitato, ma che al contempo offre soluzioni diverse. Nel caso di Dante e Calvino, ho cercato di sottolineare tutti i passi in cui era chiaramente descritto come funzionano le loro architetture. Di lì in poi ho dovuto cercare soluzioni a problemi architettonici che né Dante né Calvino avevano dovuto affrontare, in quanto le loro architetture sono fatte di parole e non di tratti. Erano comunque sempre soluzioni fornite a problemi ‘tecnici’.

D: L’ultima domanda è rivolta al lettore. Uno spiraglio sui ‘tuoi’ autori è offerto dalle Literary Architecture Series pubblicate su ‘Paris Daily Review’, ‘La Stampa’, ‘Pagina99’: in ordine sparso, Fenoglio, Faulkner, Dostoevskij, Tanizaki, Carrère, Ernaux, Conrad, Calvino, Vonnegut, Ferrante, Saer, Dürrenmatt… Quali sono i tuoi favoriti? E soprattutto, che tipo di lettore sei? Come ti poni di fronte a un’opera letteraria?

R: Tutte queste letture sono state in qualche modo sorprendenti. In realtà per sei anni avevo chiacchierato tanto ma non avevo fatto nulla, nel senso di costruire architetture letterarie. Poi il direttore de ‘La Stampa’, Maurizio Molinari, mi lanciò la sfida. La prima fu Gli anni di Annie Ernaux. La chiave di Tanizaki è un’architettura perfetta. Mattatoio n. 5 di Vonnegut è una lettura che tutti dovrebbero fare, non ha niente a che vedere con le etichette che gli hanno appiccicato, la fantascienza, l’umorismo… È uno sforzo immane condotto con una leggerezza inimmaginabile, per me è quasi eroico. Credo che sarei più pronto a ricostruire domani la cupola del Brunelleschi – con qualcuno che mi aiuta! – piuttosto che scrivere una cosa così.

Nel corso di questi anni la lettura è diventata per me una sorta di viaggio esplorativo. Mi faccio prendere per mano, se lo scrittore o la scrittrice lo vogliono, oppure mi affido al mio desiderio di esplorare la storia alla ricerca di sorprese narrative, spesso soffermandomi a osservare i dettagli, così essenziali nell’architettura come anche nella narrazione; alle volte mi trovo a gioire e godere di quello in cui mi imbatto, ogni tanto a intristirmi per le potenzialità mancate, o per dettagli progettati male.

Leggi direttamente dal sito di Arabeschi: http://www.arabeschi.it/architettura-letteraria-una-conversazione-con-matteo-pericoli-/

It’s finally here and it is so exciting to see the Laboratory of Literary Architecture in a major academic publication! The Routledge Companion on Architecture, Literature and The City, edited by Jonathan Charley, features a chapter on the LabLitArch, which includes a narrative on the genesis of the laboratory, images, project samples, the Literary Architecture series, as well as a dialogue between professors Carola Hilfrich and Jonathan Charley about the pedagogical implications of the LabLitArch.

Excerpts from the dialogue between professors Carola Hilfrich and Jonathan Charley:

“One of the valuable features of the LabLitArch project is that it seems to suggest a ludic alternative to a super-rationalized modern education system.”

“It sets up a process of playful experimentation … that has all the edginess, marginality, contingency, and frustration as well as the serious stakes in liberating our thought from habitual constraints.”

“Seeing the process at work felt like being in loophole of knowledge production; a place where participants, thrown out of the respective boxes of their home disciplines, move into a hybrid, interactive, and reconfigurable field.”

“I think of Matteo’s Laboratory as a unique environment for exploring the potential of … moments where literature and architecture, words and buildings and spaces, readability and inhabitability intertwine with humans.”

“Asking us to put our hands on works of literature by architecturally removing their verbal skins, the LabLitArch makes us grasp their actual texture rather than their form or meaning, so as to shape it, collaboratively, as a habitable space.”

“LabLitArch is perhaps most transformative for our thinking and doing at moments of counter-intuition, competing intuitions, mixed intuition, or intuitions that fail us; and that its emphasis on intuition, or gut feeling, includes loops through the whole body and its more intentional responses, as well as through the imagination and the environment.”

“Matteo’s Laboratory is itself a theory of intuition and failure. Intriguingly, its teaching method in collaboratively haptic creativity advances from the outset a non-subjectivist approach; and it does produce end-results, in the form of architectural projects.”

Details here:

https://www.routledge.com/The-Routledge-Companion-on-Architecture-Literature-and-The-City/Charley/p/book/9781472482730

And here:

http://lablitarch.com/2018/12/lablitarch-in-routledge-academic-anthology/

Some images and a video from the incredible and intense, 5-day-long May 2016 edition of the LabLitArch in Jerusalem, held in collaboration with The Hebrew University‘s Department of Comparative Literature, the Bezalel Academy‘s Department of Architecture, and Da’at HaMakom (The Center for the Study of Cultures of Place in Jewish Modernity).

Some images and a video from the incredible and intense, 5-day-long May 2016 edition of the LabLitArch in Jerusalem, held in collaboration with The Hebrew University‘s Department of Comparative Literature, the Bezalel Academy‘s Department of Architecture, and Da’at HaMakom (The Center for the Study of Cultures of Place in Jewish Modernity).

Images: http://lablitarch.com/2016/05/lablitarch-edition-in-jerusalem/

By AJ Artemel

Writing has long been intrinsic to the practice of architecture, from Vitruvius’s Ten Books on Architecture to the theoretical essays of Peter Eisenman. Writing helps architects explain ideas that are hard to glean from drawings alone, and allows for the setting out of non-project-specific agendas in manifestos or magazines, such as Le Corbusier’s L’Esprit Nouveau. Theoretical writers have engaged with architecture, as well; Jacques Derrida, for example, used architectural metaphors to describe the structures of texts and advised architects on the Parc de la Villette competition. Architects have also figured as characters in works of fiction, perhaps most memorably in Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. But rarely has architecture served the same function for writing as writing has served for architecture: to analyze and clarify.

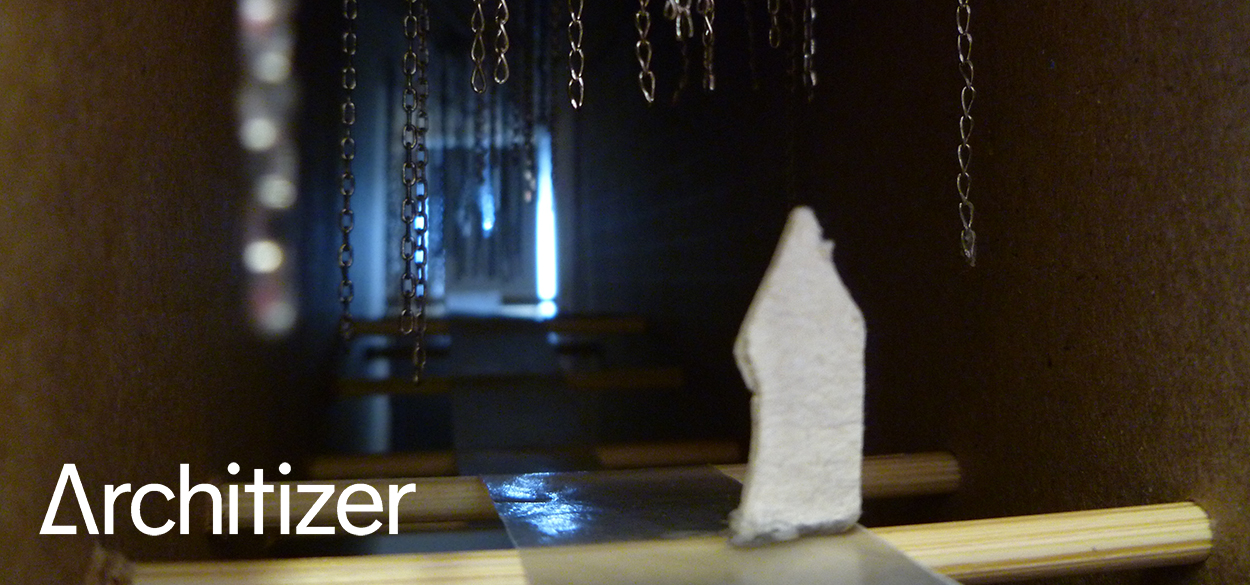

This past spring, Columbia University School of the Arts writing students set out to do just that, in Professor Matteo Pericoli’s workshop, the Laboratory of Literary Architecture (Pericoli has also taught the course at the Scuola Holden in Turin for the past four years). The thirteen students each started with a literary work they knew well, and carefully stripped away its language to reveal the structures and spaces that organize it. These hierarchies, sequences, and literary volumes were then translated into architectural models with the assistance of Columbia architecture students (see the projects below). Under Pericoli’s instruction, students strove to represent the literary, not the literal.

The inspiration for the models starts with reading. As Professor Pericoli writes, “When I read a novel, an essay, or some well-structured (other than well-written, of course) piece of writing, there is a moment when I have the feeling that I am inhabiting a structure that goes beyond its words, that was somehow built (I am not sure how consciously) by the writer. And I am not talking about settings described in the book.” But the hope is that analyzing literature with architecture will eventually help students become better writers. Pericoli adds, “What matters, I think, is that [students] realize that creating a piece of writing in your mind can be a spatial and structural exercise—before, during or after you have begun to put actual words on paper. For a writer, thinking wordlessly may turn out to be a positive experience.”

While the class is specifically intended to develop writers’ ability to think spatially, the architectural outcomes of the class show the students’ strong understanding of space, and how to manipulate it with surfaces and volumes. The designs range from sparse and ethereal pavilions to models that seem well on their way to becoming buildings. Many of the pavilion designs adopt a memorial-like simplicity, adhering to a few cuts in the ground or a group of walls. This similarity may stem from the need to create spaces for the narratives of the reader or the visitor (in the students’ explanatory essays, these are often one and the same), or from that elusive sense of architectural poetics.

The more building-like projects seem to stem from works in which the author sets forth a strong, repetitive or clear structure, as in David Foster Wallace’s “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again.” The power of this structure is more easily conveyed into floorplates, stairs, and elevator shafts, and sheds light on how architects themselves might go about diagramming an initial idea.

The Laboratory of Literary Architecture succeeds in bringing writing and architecture closer together than ever, by equipping writers with an architect’s vision and mode of analysis. Architects can learn from this experiment, too; perhaps architecture schools should reintroduce writing classes where possible, in order to teach architects how to think in narrative, in metaphor, and ultimately, to translate these concepts into imaginative spatial structures.

Read the piece and look at project photos and texts from Architizer:

https://architizer.com/blog/inspiration/industry/when-writers-become-architects/