With his drawings of Manhattan, Matteo Pericoli won New Yorkers over (and then the rest of the world), then went back to Italy, to Turin, to work on architecture, stories, and their relationship.

by Manuel Orazi

Many in literature have used the metaphor of architecture, especially to shape the structure of a novel; however, very few have done the opposite: imagining architecture as a narrative structure. This is the original interpretation of Matteo Pericoli, a man who, after leaving his profession in architecture, backed into it again.

After graduating from Politecnico di Milano university under Wolfgang Frankl – one of Mario Ridolfi’s historical collaborators – right before his passing, Pericoli moved to New York to work for Peter Eisenman for a brief period and then for Richard Meier. Between 1995 and 2008, the Big Apple was the setting for his metamorphosis from architect to illustrator; he conquered the city that never sleeps, which he drew from the outside first and the inside after (in Manhattan unfurled and Manhattan within).

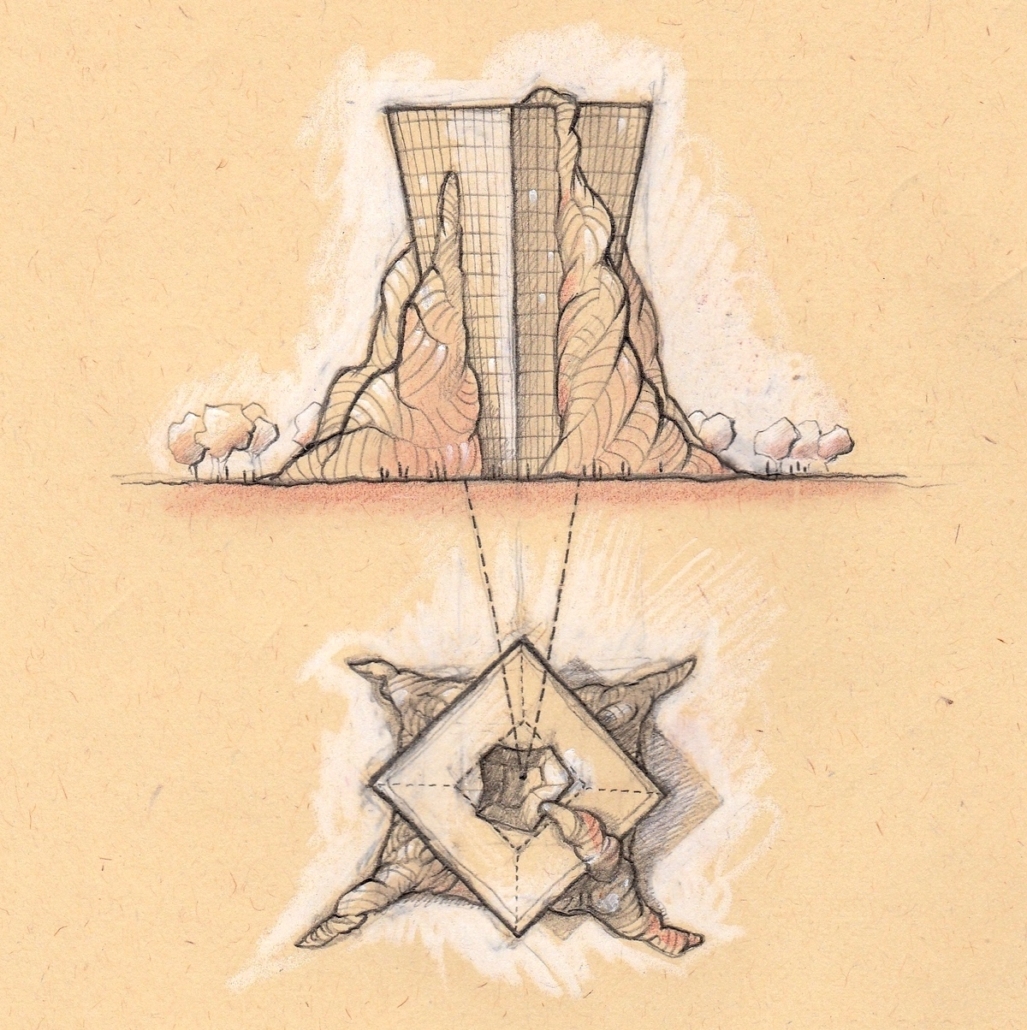

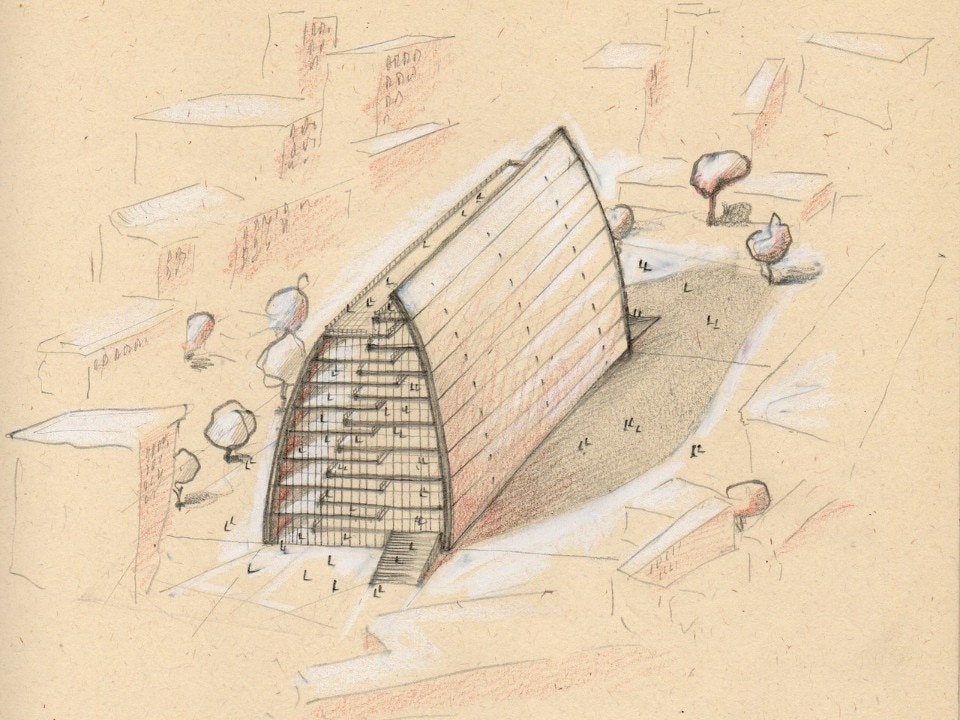

What if the architecture of a novel were a real building – that is, it had a physical, tangible structure made of more than just words – what shape would it take?

Paul Goldberger, then critic for The New Yorker, wrote that Pericoli managed to win New Yorkers over because he was the first to gather the entire urban profile of the island in a single roll, to draw Manhattan as if it were a town from his birth region. After many years and many other literary adventures that brought him to work with some of the most renowned international newspapers, Pericoli went back to Italy, but not to Marche, the region where his family is originally from, but to Turin.

There, he found the Scuola Holden, where he proposed a completely new way of perceiving literature: “stories need to be experienced mentally before they can be written.” So, are stories landscapes, are they doors? “Not really, a story is not like a road to follow… it’s more like a house. Like the Nobel price Alice Munroe explained, you go inside and stay there for a while, wandering back and forth and settling where you like and discovering how the room and corridors relate to each other, how the world outside is altered by being viewed from these windows. And you, the visitor, the reader, are altered as well by being in this enclosed space, whether it is ample and easy or full of crooked turns, or sparsely or opulently furnished.”

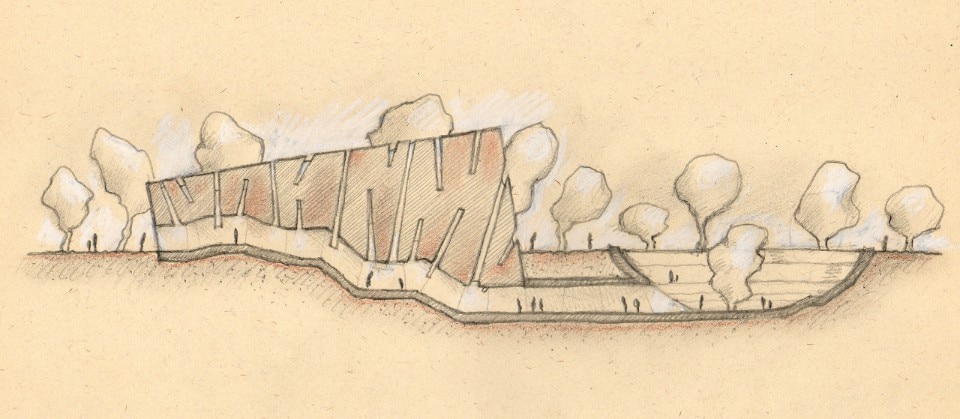

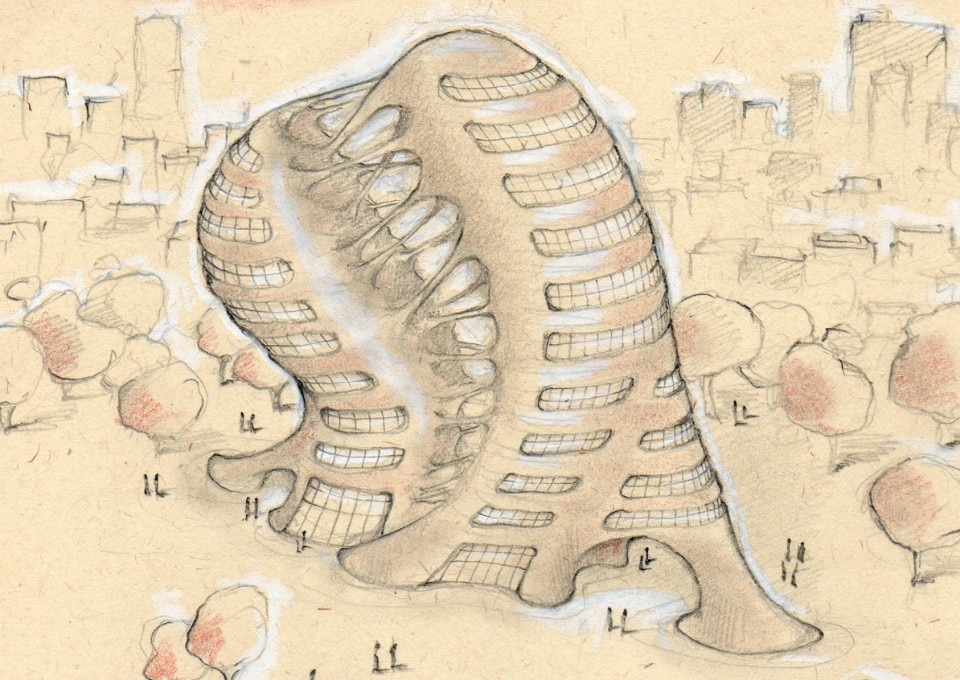

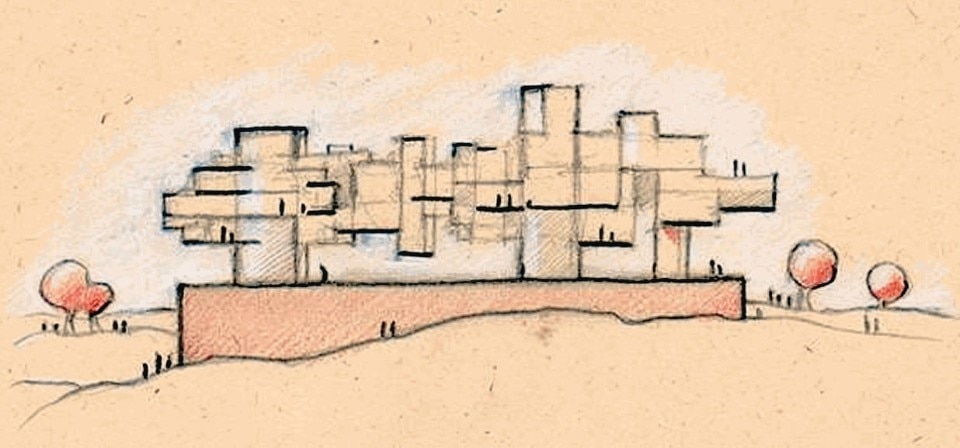

So you can even go back again and again, of course, “the house, the story, always contains more than you saw the last time. It also has a sturdy sense of itself of being built out of its own necessity, not just to shelter or beguile you.” The result is a collection of curious drawings, now gathered in a book, The Great Living Museum of the Imagination, which is probably the most ambitious of his books, the crowning achievement of this second Italian life of his. It certainly is the most theoretical of his publications.

Pericoli’s intellectual candor echoes that of Gianno Rodari and his The Grammar of Fantasy: An Introduction to the Art of Inventing Stories, published over fifty years ago, the only theoretical text by Rodati, which makes it particularly significant. In the back cover of the 1973 edition, Rodari wrote: “I insist on saying that, although Romanticism surrounded it with mystery and created a sort of cult around it, the creative process is inherent to human nature and therefore it is within everyone’s reach, with everything this entails in terms of happiness to express and play with one’s imagination.”

Similarly, Pericoli encourages everyone to this exercise, trying to unravel some of the big, abstract questions without ever wanting to present himself as a philosopher or a critic, but suggesting practical solutions that are accessible to everyone. And he does so, for instance, by posing the question: what if the architecture of a novel were a real building – that is, it had a physical, tangible structure made of more than just words – what shape would it take?

It’s a question that Pericoli has been trying to answer for more than a decade together with his students at the Laboratory of Literary Architecture, which started at the Scuola Holden and then extended to other universities as well: “Reception creates interpretations that translate into shapes that are completely different depending on the student that conceives them, no two are the same.” The drawn, often bizarre, structures stress a fundamental fact: the process of reading of a text is just as creative as the process of its writing (maybe even more so), “the choices that are made when building architectural structures are very similar in quality to those made by a storyteller…It has the same feeling as a collaboration between two active sources rather than being a monodirectional transmission > reception process.”