Di Matteo Pericoli

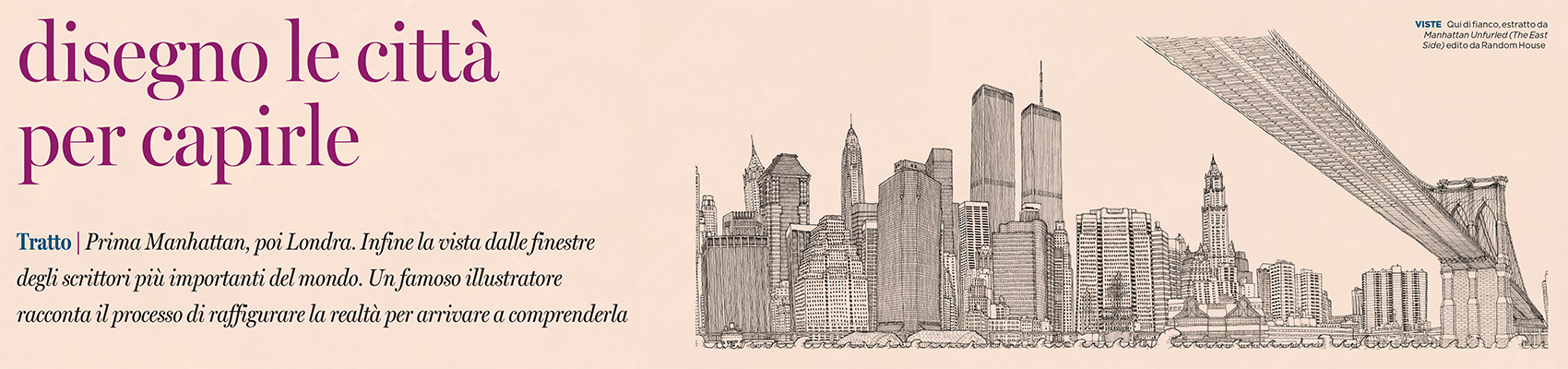

Un diario tenuto dall’1 marzo 2002 al 24 febbraio 2003 che accompagna il disegno a fisarmonica di oltre sei metri in Il cuore di Manhattan (Bompiani, 2003)

[Click here for the English version]

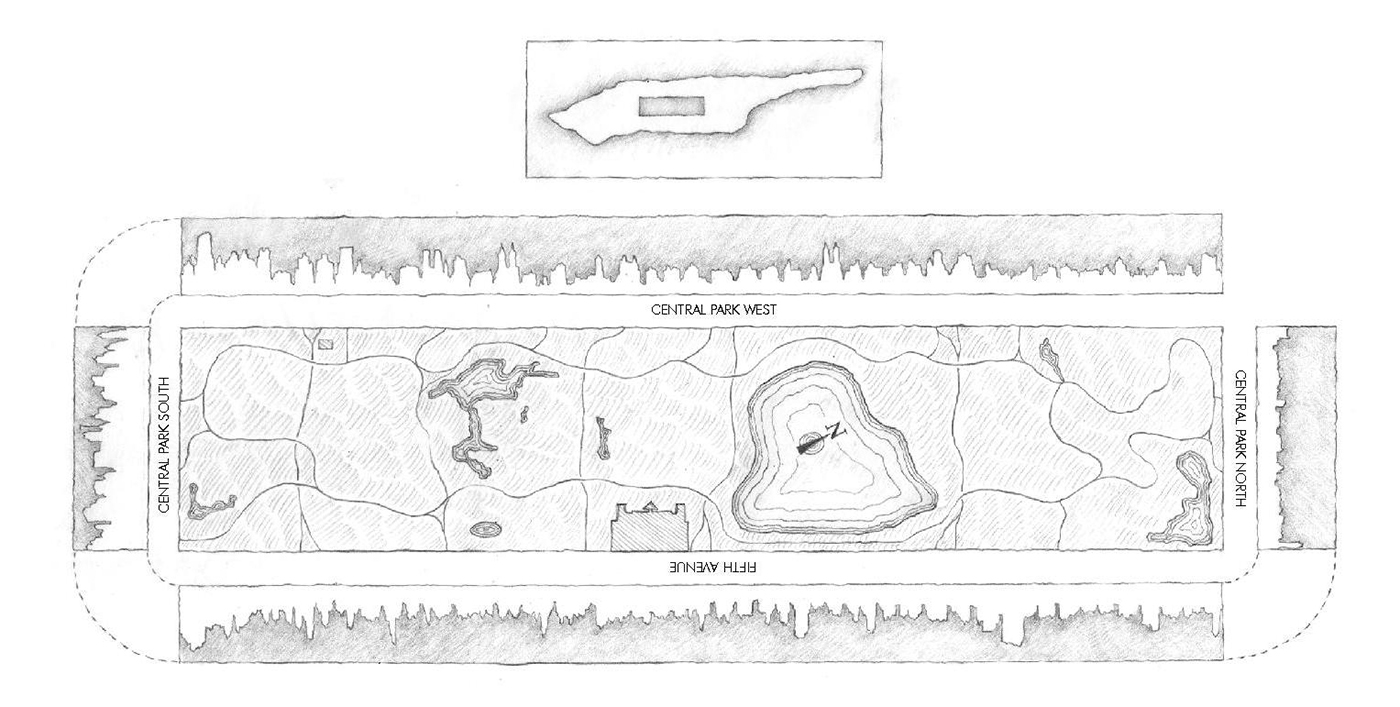

Nel maggio del 1998 presi per la prima volta la Circle Line, il battello che circumnaviga l’isola di Manhattan. Quelle tre ore di navigazione furono all’origine del libro pubblicato nell’ottobre del 2001, Manhattan svelata, che mostra integralmente sia l’East Side che il West Side dell’isola visti dall’acqua. Nel marzo del 2002 ho incominciato a lavorare a un disegno della città vista da Central Park. Queste pagine sono basate sul diario che ho tenuto durante il periodo di tempo in cui ho lavorato al disegno, dall’inizio alla fine.

È finalmente giunto il momento di mettere mani e strumenti sulla carta. I quasi dieci metri di rotolo che ho davanti sono bianchi e terribilmente lunghi. Ho passato gli ultimi mesi a fare schizzi, a scattare foto, a provare una tecnica dopo l’altra, sempre sapendo che, tanto addentro nell’isola, il disegno non può essere semplicemente in bianco e nero, inchiostro su carta. Dev’essere a colori. Deve sembrare fatto di materia. Non c’è solo acqua fra me e la città, c’è della vegetazione stavolta, ci sono foglie, terra, boschi e prati.

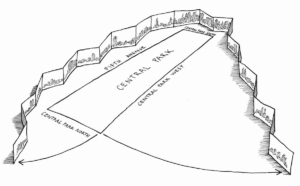

Ho fatto dei primi calcoli approssimativi: il parco è lungo 51 isolati e largo l’equivalente di più o meno dieci strade, perciò il perimetro è di circa 122 isolati. Questo significa che, per far stare il disegno nel rotolo che ho scelto, ciascun isolato dovrà misurare circa otto centimetri. Il resto dovrà essere improvvisato. Vorrei evitare che il disegno risulti troppo esatto. Sto entrando ora nel parco dall’angolo nord-ovest, e mi lascio alle spalle – o meglio, tutt’intorno – i rumori della città. Entro. Poi mi girerò per guardarmi indietro.

Ho fatto dei primi calcoli approssimativi: il parco è lungo 51 isolati e largo l’equivalente di più o meno dieci strade, perciò il perimetro è di circa 122 isolati. Questo significa che, per far stare il disegno nel rotolo che ho scelto, ciascun isolato dovrà misurare circa otto centimetri. Il resto dovrà essere improvvisato. Vorrei evitare che il disegno risulti troppo esatto. Sto entrando ora nel parco dall’angolo nord-ovest, e mi lascio alle spalle – o meglio, tutt’intorno – i rumori della città. Entro. Poi mi girerò per guardarmi indietro.

***

Vista dal parco, la città sembra sorgere da una nuvola di alberi. Nessuno degli edifici rivela la sua base, le sue radici. Tutti fluttuano invece al di sopra della nuvola verde.

Fuori del parco, per potersi orientare nella griglia urbanistica della città, bisogna conoscere le proprie coordinate – un’avenue e una delle strade che la attraversa. Nel parco, per capire dove ci si trova, bisogna guardare fuori, verso gli edifici.

Il disegno si concentrerà sugli edifici che si affacciano direttamente sul parco e sullo skyline che si portano sulle spalle, su una linea, una linea immaginaria e mutevole, che si crea dove il parco finisce (le cime degli alberi) e la città incomincia. Il parco nel disegno svanirà perché mi servirà solo come punto di osservazione da cui vedere lo skyline interno di Manhattan.

***

In cerca dei pezzi mancanti del puzzle che sto provando a ricostruire. Oggi sto lavorando a una porzione di Central Park North. L’aspetto finale del disegno sarà una mescolanza di ciò che ho fotografato e di ciò che ho annotato nei miei schizzi – il tutto unito a una buona dose di invenzione. Il disegno finirà per essere qualcosa che non esiste in realtà, o meglio che in realtà è visibile solo a pezzi e mai integralmente.

Camminare per il parco “in cerca” della città rappresenta quello che dovrebbe essere lo spirito di questo lavoro: andare a caccia di uno skyline al contrario, rovesciato; osservare come si mostra la città quando guarda il proprio centro, il proprio cuore, al limite del suo confine interno, e non come la vede il mondo, dal di fuori. Eppure, mentre camminavo fra gli alberi stamattina, mi è parso improvvisamente di non essere entrato più addentro nella città, ma di esserne invece appena uscito.

***

Oggi ho lasciato la città e sono entrato di nuovo nel parco all’angolo della 110ma Strada con Central Park West e ho camminato lungo il bordo giù fino alla 66ma Strada. Ero dentro al parco, ma non troppo dentro, e saltavo sassi e aggiravo tronchi per guardare la città che stava fuori, in cerca di un’apertura fra i rami che rivelasse un pezzo di skyline da aggiungere a quello appena visto prima. Il parco è già bello per sé, ma è lo sfondo della città che lo rende magico. La maggior parte delle foto di Central Park che la gente scatta o che ho visto su cartoline o in vari libri su New York mostrano tutte la stessa cosa: mai gli edifici da soli, o il parco per conto suo, ma l’unione, il contrasto delle due cose messe insieme.

***

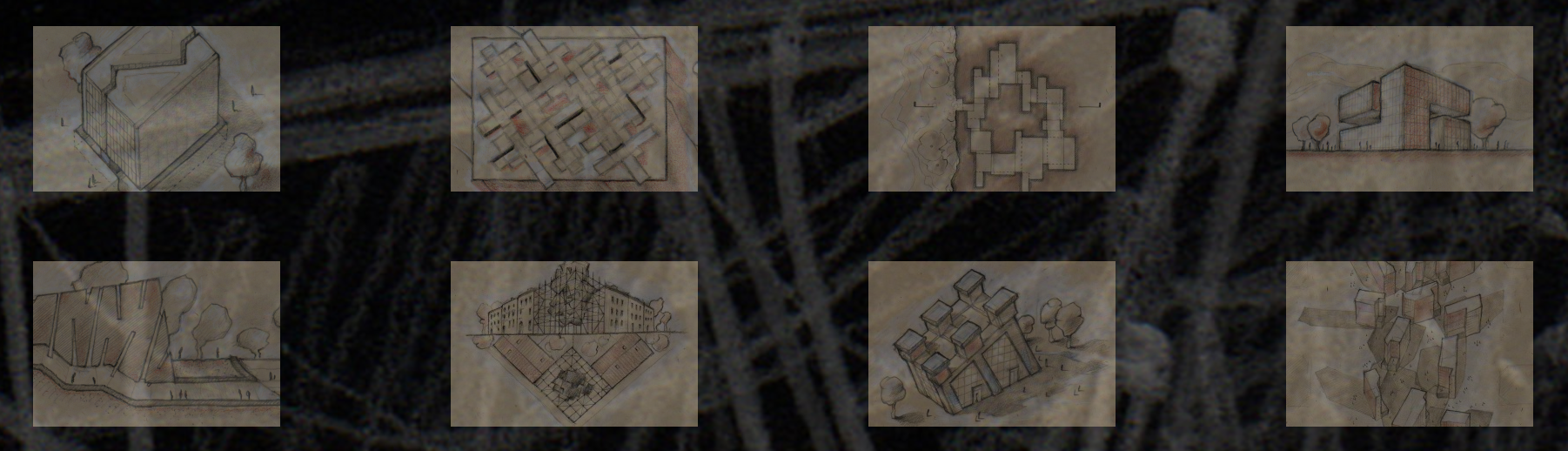

Tutte le foto che mi servono (decine per ogni isolato) e i miei appunti sono sparpagliati sulla scrivania. Un caos. Il rotolo di dieci metri di carta è avvolto su due rocchetti di legno, uno a ogni estremità. Una porzione del rotolo di circa 60 cm è aperta davanti a me, pronta per il lavoro. Quello che ho già completato è avvolto sul rocchetto di sinistra; il resto del disegno (circa nove metri) è avvolto su quello di destra. Siccome disegno con la destra, mi sposto lungo il perimetro del parco in senso orario. Da qualche parte in mezzo a questo caos ho delle banalissime matite (per il primo schizzo sommario), delle matite colorate, i pastelli a olio, una punta di acciaio e un set di matite di grafite più dure e precise.

Le varie foto sparse davanti a me ritraggono la porzione di skyline a cui intendo lavorare. Mostrano le diverse facciate dei diversi edifici, da molti possibili punti di vista, in varie stagioni e condizioni di luce. All’inizio fisso queste immagini a lungo. Ho bisogno di assorbirle e comprenderle. Devo isolare ciascun edificio, capirne la relazione con quelli vicini e scoprire le sue caratteristiche principali, o meglio il suo carattere.

A un certo punto, durante questa fase, sembra essere arrivato il momento giusto per mettere giù un primo schizzo degli isolati che sto studiando. Schizzo gli edifici, i loro profili, le loro proporzioni, e scelgo un punto di vista per la prospettiva. La prima volta di solito non funziona, quasi mai. Questo schizzo rappresenta una serie di possibilità: molte linee si intrecciano, e lo stesso edificio può comparire in più di un posto o in più di una posizione.

Gli edifici appena finiti (arrotolati alla mia sinistra) mi aiutano a stabilire la dimensione dei successivi. Quelli più grandi sono pericolosi perché rischio di sopravvalutarne le dimensioni e di trovarmi poi senza spazio verticale sufficiente sulla carta.

A questo punto prendo le matite colorate e ripasso tutte le linee che mi interessano – tutte le linee che fissano gli edifici e che riproducono i loro tratti fondamentali: altezza, larghezza, profondità, profilo, ma ancora senza dettagli, senza finestre ecc. Scelgo un’immagine tra le tante. Le matite sono di vari colori: blu, rosse, giallo scuro, arancio, violetto e così via. Le uso a caso, poi prendo i pastelli a olio e copro tutto lo schizzo con uno spesso strato di colori tenui: crema, azzurri, gialli chiari, arancio e bianco o bianco sporco. Mi sporco le mani con i pastelli a olio e lo schizzo a matita scompare, coperto quasi completamente dall’olio. Riesco a malapena a distinguere le linee del disegno sottostante.

Questo è il momento di prendere la punta d’acciaio, una sorta di bulino, e incominciare a grattare, in cerca delle linee nascoste. Le trovo qua e là – ma non trovo elementi precisi, netti, univoci. Sono linee confuse, combinazioni di molti graffi in molte direzioni. È come scavare per riportare alla luce una città sepolta. Ogni linea che trovo mi fornisce una traccia, un indizio sulla città da scoprire e un indizio sul mio stesso disegno. A volte ricordo quello che ho fatto e vado a memoria; altre volte mi domando: “Dove cavolo ho messo quella linea?”

È questa la parte più emozionante del lavoro, durante la quale non so esattamente cosa sto facendo. Mi limito a cercare e a reagire a quello che vedo emergere davanti a me. Non è possibile sbagliare, perché se gratto dove non ci sono linee vado a cercare da un’altra parte. La linea, essendo il risultato di una serie di tentativi, simboleggia lo spirito di quello che voglio fare; questo skyline non è lo skyline, l’unico possibile skyline, ma la somma di molte possibili porzioni di uno skyline che, nel suo insieme, è invisibile.

Continuo a raschiare. Lentamente il disegno riemerge. Riemerge la città. La città sorge dalla carta e mi si mescola ai pastelli a olio.

Dopo che gli edifici sono riapparsi, prendo le matite di grafite più precise – molto più dure e molto appuntite – per dar forza ai volumi, e continuo a scolpire le forme aggiungendo i dettagli, i particolari, le finestre. A questo punto di solito mi viene un po’ di nausea, perché questi edifici hanno un indicibile numero di finestre, aperture, vetrate ecc.

Quando la nausea passa, riprendo il bulino e gratto via il pastello a olio da tutte le finestre, per dar loro profondità. Infine, con una matita più morbida, aggiungo una linea a “L” a due lati di ogni finestra, per fissare e dar profondità all’apertura.

***

Ognuno dei quattro lati di Central Park mostra una faccia diversa della città. Immaginate di tagliar via un pezzo quadrato dal centro di una torta e di mettervi all’interno di quello spazio. Guardando verso l’esterno, verso i quattro lati, vedreste gli strati interni della torta, di cosa sono fatti, tutti i colori e le consistenze dei diversi ripieni – crema, marmellata e così via. Ma non vedreste nessuna differenza tra un lato e l’altro. Mentre nel parco – ed ecco la grande differenza fra l’esperimento della torta e l’esperienza di Central Park – ciascun lato è unico.

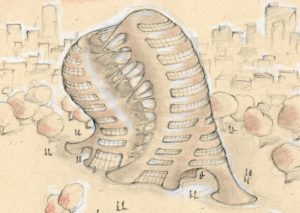

Central Park è stato scavato dalla griglia urbana di Manhattan quando intorno ad esso era stato costruito ancora molto poco, se non addirittura nulla. Quando la città è poi cresciuta a dismisura e si è impadronita dell’isola, quel primo taglio è rimasto intatto. Adesso, guardando verso sud dall’interno del parco, vediamo l’incredibile forza delle strutture di midtown che spingono verso nord; guardando verso est e verso ovest, vediamo gli eleganti palazzi di appartamenti del primo Novecento a due torri, le decorazioni in stile art-déco e svariati musei; guardando verso nord vediamo Harlem, una parte della città più dolce e architettonicamente più delicata, con edifici non troppo alti, o a volte tanto bassi che dal parco non li si vede neppure. Il loro rapporto con il parco è dei più naturali, come quello di una cittadina di provincia con i campi coltivati dei suoi dintorni. I lunghi isolati di Central Park North, con edifici bassi uno dopo l’altro e centinaia di scale antincendio in metallo che riflettono la luce che le colpisce da sud, ispirano emozioni molto diverse dalla congestione architettonica di Central Park South, a cinquantun isolati di distanza. Il Rockefeller Center e gli altri grattacieli della folta giungla di midtown incombono sulla prima fila di edifici lungo Central Park South; quasi li fanno ribaltare. Il grattacielo alle spalle dell’hotel Plaza, quello con la base inclinata, sembra costruito così proprio per resistere a chi lo spinge da dietro.

***

La prima svolta si rivela più facile del previsto. Di tutte le piccole bugie che questo disegno racconta, girare l’angolo, ruotare di 90 gradi per passare da un lato all’altro, è probabilmente la più grossa. L’angolo dev’essere appiattito nel disegno per non interromperne la continuità. Qui, all’incrocio fra Central Park North e la Fifth Avenue, i due alti palazzi di appartamenti funzionano perfettamente da perno per la svolta: lo spazio tra di loro è il vuoto attorno al quale passerò dal guardare a nord (verso Central Park North) al guardare a est (verso la Fifth Avenue). La città sullo sfondo seguirà, come l’asta di un compasso. Le due viste si mescolano facilmente l’una all’altra e l’angolo si apre. Più giù, agli angoli più importanti, dove Central Park South incrocia la Fifth Avenue o Central Park West, la città ti circonda invece come un anfiteatro, e le sue masse ti premono con forza dall’alto.

***

Ancora al parco a fare foto e a prendere appunti. Un freddo pazzesco, ancora, il che fortunatamente significa niente foglie sugli alberi, ma anche che le mie estremità sono congelate. L’inverno è il periodo migliore per godersi le viste della città, ma anche il più difficile per catturarle. I miei guanti imbottiti rendono estremamente difficile premere il pulsante della macchina fotografica e pressoché impossibile tenere la matita in mano.

Ormai devo avere fatto almeno ottocento foto e sto incominciando a riconoscere gli edifici, anche quelli che non ho ancora disegnato. Malgrado ciò, non mi sembra di poter dire che conosco qualcosa finché non l’ho disegnata. Mi domando cosa vediamo veramente quando andiamo in giro, o anche quando facciamo delle foto. Penso sempre al momento in cui disegnerò quello che sto fotografando, perché allora, e per me solo allora, arriverà il momento di capire, imparare e conoscere.

***

Oggi stavo guardando Central Park West dall’estremità est dello Sheep Meadow, quando una signora alle mie spalle dice: “Che splendida opera d’arte”. Quell’osservazione mi ha colpito perché in effetti si trattava di una vista incredibile, ma a quale “opera d’arte” si riferiva? Al parco? All’erba del prato? A un edificio in particolare? Chi era l’artista? Frederick Law Olmsted, che ha progettato il parco? O gli architetti che hanno progettato gli edifici lungo Central Park West? Tutti loro, ma anche tutti noi, senza dubbio. Loro che hanno dato vita a tutto questo, e noi che lo amiamo.

Ci sono posti unici e splendide architetture dappertutto, e si possono dividere in due categorie: posti che sono consapevoli della propria bellezza e posti che non lo sono. Manhattan appartiene a questi ultimi. La sua bellezza è naturale, perché quello che amiamo non è stato pensato semplicemente per il nostro piacere, ma è stato progettato per ragioni pratiche. Pensate alla griglia stradale, allo sviluppo urbano selvaggio spinto dall’economia. Pensate al bisogno di salire verso l’alto a causa del costo dei terreni o al piano regolatore del primo Novecento, che imponeva la costruzione di terrazzature agli edifici man mano che aumentavano in altezza. Tutto questo ha prodotto ciò che vediamo e apprezziamo oggi. (Nessuno ha progettato le viuzze tortuose di tante città medievali italiane per creare vedute piacevoli per i turisti. Una strada tortuosa segue meglio la topografia della zona, crea una barriera contro i rigidi venti invernali ed è più facile da difendere.) Il parco è stato il risultato di una lotta vinta da persone comuni per assicurarsi un bene fondamentale: aria pulita.

Si potrebbe perciò dire che quella vista non è “un’opera d’arte”, dato che non è frutto di una decisione individuale, e che in realtà è New York, la città stessa, che prende queste decisioni, con una propria vita e un proprio cervello. La sua struttura e i suoi meccanismi interni sono alla base della creazione quasi automatica di opere d’arte. È difficile sbagliare, perché è difficile rovinare un sistema che assorbe praticamente qualsiasi cosa, la assimila e ce la restituisce come parte di sé.

Faccio fatica a osservare e a giudicare gli edifici di New York in sé e per sé. Molti non sono belli, molti sono decisamente mal riusciti, forse, ma avrebbe senso dire ciò solo se fossero da un’altra parte, completamente isolati. Qui non mi paiono brutti. Non si può pensare allo skyline semplicemente come a una somma delle sue parti. Lo skyline non è la somma degli edifici che lo compongono contro il cielo. È qualcosa al di là e oltre – qualcosa che trascende gli edifici e vive di vita propria.

***

Fra pochi giorni il parco si riempirà di verde. Gli uccelli torneranno e una spessa coltre di foglie attenuerà gran parte del rumore cittadino e oscurerà la visuale. La città sembrerà arretrare. Le vedute nei periodi “verdi” dell’anno mostrano una città distante, più lontana e misteriosa.

***

L’altro giorno stavo facendo delle foto da un appartamento al dodicesimo piano di un palazzo sulla Fifth Avenue e la 98ma Strada. Vista stupenda, appartamenti magnifici. Ne ho visti più di una dozzina. Era come una catena: qualcuno il cui appartamento avevo visitato di recente telefonava a un amico in un’altro palazzo e così via. Quelli che mi davano il benvenuto nella loro casa sembravano tutti avere la stessa opinione sulla vista di cui godevano: c’era un sentimento di orgoglio nel modo in cui mi portavano alla finestra, quella era la loro vista – non il mondo fuori dalla finestra, bensì un’estensione del loro appartamento. Un’altra stanza. Sentivo la presenza tangibile della città nella loro vita.

Le foto da questi appartamenti mi sono essenziali per capire e organizzare le informazioni raccolte dal parco: dall’alto posso vedere la massa della città che preme sul parco molto più chiaramente che dal basso. Il passaggio dal parco alla città è improvviso e violento. Non c’è transizione. Da molto sopra la cima degli alberi, il mare verde e la densa vita della città si toccano senza mai sovrapporsi, come se ci fosse un muro invisibile a separarli. Come una città antica che si difende non dal mondo esterno, ma da qualcosa al suo interno. Come una città che abbia costruito delle mura rettangolari, lasciando l’interno del rettangolo vuoto – perché quello è il mondo esterno – e costruendo solo all’esterno. Sarebbe una città piuttosto strana.

***

Penso che questo sia il vero skyline di Manhattan. Dal parco, tutti gli edifici sembrano guardarmi. Quando lavoravo allo skyline lungo il bordo esterno della città, gli edifici che vedevo mi davano le spalle, come se a loro non importasse nulla di me.

***

Mi ricordo quando, poche settimane dopo essermi trasferito a New York, nel dicembre del 1995, venne un’enorme nevicata. Nel giro di alcuni giorni caddero metri e metri di neve. La città si fermò, come un corridore che si ferma per prendere fiato e per scrollarsi la neve dalle spalle.

I volumi, le forme, le dimensioni degli edifici della città erano cose a cui dovevo ancora abituarmi. Appena sbarcato dall’Italia e ancora fresco dei miei studi ed esperienze architettoniche italiane, camminare a fianco di edifici più alti di dieci piani, o sotto strutture sospese per più di cinquanta metri, esigeva un completo riaggiustamento dei miei sensi. (Qualsiasi luogo viene colto prima con i sensi, e poi spiegato o apprezzato con il cuore e con la mente.) Il rumore e l’odore della città erano altrettanto nuovi. Una passeggiata pomeridiana a midtown, per uno appena sceso dall’aereo, non è un’impresa da poco: le macchie gialle dei taxi punteggiano i fiumi di macchine con i loro colori e i loro clacson, vapori fuoriescono da buchi nel terreno, la luce del sole raramente riesce a penetrare la densità e la mole degli edifici, la cui cima resta spesso invisibile, perché è arretrata e troppo alta per poterla vedere. Costruzioni e trasformazioni dappertutto. Nulla sembra rimanere fermo. Un tumulto di sensazioni che frustravano i miei genuini sforzi per vedere e capire questo posto. Ma fortunatamente un giorno (o meglio una notte) cadde la neve e con essa una coltre di silenzio si posò sulla città – così come mia nonna, con un gesto fermo e armonioso, stende la tovaglia sulla tavola prima di apparecchiarla per il pasto. Tutto si fermò – autobus, metrò, macchine. Potevo passeggiare ovunque, in qualsiasi momento. Potevo alzare gli occhi senza paura di urtare qualcuno o di essere investito da un’auto. Mi si aprirono nuove prospettive sulla città. La mia vista si fece più acuta, come quella di un guidatore che abbassa il volume della radio per fare attenzione ai cartelli stradali.

Quel silenzio è stato uno dei regali più belli che la città mi abbia fatto. Mi ha aiutato a rendere quegli enormi volumi, dimensioni, proporzioni, un po’ più miei, a dar loro una forma umana. Mi ha aiutato a entrare in relazione con loro. Ho visto l’Empire State Building, i canyon lungo la Sixth Avenue a midtown, le irraggiungibili cime di tutti quei grattacieli come non era previsto che li vedessi: domati e resi silenziosi dalla natura, costretti, come tutti noi, ad aspettare che la tempesta cessasse per poter riprendere il loro solito ritmo e riacquistare la loro solita forza. Non c’era differenza, in quel momento, fra loro e me. Il caos che in breve tempo ritornò non ha mai cancellato quel ricordo.

***

Un disegno è fatto di linee, le linee sono un’astrazione della realtà, e in quanto tali sono delle finzioni. Devono essere inventate di volta in volta. Le linee di un disegno sono il risultato di una complessa (benché intuitiva) serie di decisioni riguardanti la realtà, di scelte su come mostrare qualcosa che non esiste più di quanto esista l’orizzonte. Un disegno porta con sé le parole “ecco ciò che penso” più che le parole “ecco ciò che vedo”.

Le linee si possono disegnare in molti modi, usando diverse tecniche, ma ciascuna ha un significato particolare, un’intenzione. Collegare un punto con un altro sembra essere l’unico scopo di una linea. Ma c’è ben altro: c’è il come. Come una linea è tracciata rivela la profondità, la conoscenza e il grado di astrazione che si vuole comunicare. Disegnando una linea io posso mostrare accuratamente la geometria della bottiglia che ho di fronte, ma potrei anche tentare qualcosa di più: potrei usare la matita per creare una linea che senta la curva del collo della bottiglia; potrei trattare in modo diverso la linea che rappresenta il cilindro rispetto a quella dell’imboccatura; e metà dell’apertura rotonda sarà più vicina a me, per cui la linea dovrebbe comunicare anche questo, e così via.

Quando si guarda un disegno altrui, e si riescono a seguire i percorsi della penna o della matita, si può risalire o all’occhio che ha scrutato il mondo o alla mente che ha scavato nell’immaginazione. Disegnare dal vivo, o rifare un disegno già fatto da qualcun altro, incide nella mente quello che si sta guardando.

Come in un testo, si può essere ambigui, si può insinuare, o si possono usare troppe linee o troppe parole per descrivere qualcosa quando se ne potrebbero usare meno, riducendo la quantità di informazioni a un minimo convincente. Leggerezza e precisione possono essere espresse da una linea o da una frase (non la precisione della linea tracciata col righello, ma la precisione che deriva dal servire a uno scopo). Una linea disegnata per generare la forma di un’architettura umanizza una veduta, così come una descrizione calda e intensa del sole che illumina un palazzo ad una certa ora del giorno. Le parole possono far pensare, così come le linee possono far vedere quello che non si era immaginato prima.

***

Come molti altri visitatori, ho passato i miei primi giorni a Manhattan lamentandomi del dolore al collo perché tentavo di guardare la cima dei grattacieli, che sembravano progettati per essere osservati dalla loro altezza, non dalla mia. I dettagli più belli erano tutti lassù, in mezzo alle nuvole. Prima di essere costruito, ciascuno di questi edifici è stato sul tavolo da disegno di un architetto, e siccome in un disegno la base, il centro e la cima sono visibili nello stesso tempo, non fa differenza se l’edificio è alto trenta metri o trecento; si cambia semplicemente la scala. Perciò, fin dall’inizio, mi ha interessato più il rapporto tra gli edifici di Manhattan e il cielo che il loro rapporto con il suolo. Incantato dall’altezza, e dalla bellezza della cima di questi giganti, non trovavo altrettanto emozionante ciò che si svolgeva ai loro piedi. In Italia, ciò che conta è come un edificio sbuca dal terreno, il suo rapporto con la piazza circostante e con noi, esseri umani. Le grandi eccezioni sono le cupole, strutture cave costruite per far sì che l’anima si elevi al cielo e fatte per essere viste da lontano. Ma in una cupola quello che conta è l’interno vuoto, non la struttura in sé. Qui, invece, ciò che conta è la domanda: “Cosa farà il palazzo quando incontrerà il cielo?” È un nuovo tipo di rapporto, non fra l’architettura e la città, o fra l’architettura e le persone, o fra l’architettura e lo spazio, ma fra l’architettura e il cielo.

***

Guardare, seguire questo disegno su un lungo rotolo di carta è come svolgere una storia. L’inizio e la fine appartengono a due momenti diversi. Sono distanti sia fisicamente, sia cronologicamente. Mentre lavoro, non riesco a vedere né l’inizio (arrotolato alla mia sinistra), né, naturalmente, la fine (alla mia destra). Una linea immaginaria segna l’avanzare del lavoro e separa ciò che è finito e pronto a essere stampato da ciò che ancora non esiste. Il rotolo, in effetti, è una serie di sessioni terminate. Dopo ciascuna, avvolgo un altro po’ di carta e ricomincio da zero: schizzo a matita, aggiungo i colori, poi i pastelli e così via. Le nuove porzioni risulteranno unite alle precedenti, ma ciascuna è per me un nuovo disegno, una nuova esperienza: nuovi edifici da capire, nuove proporzioni, nuove scoperte. I molti capitoli di una storia, che si svolge nel tempo e nello spazio, e che si lascia alle spalle ciò che è stato già detto.

***

Se si vuole capire una città europea – Roma, per esempio – è necessario prima di tutto sedersi e leggere qualche libro. Bisogna cominciare a scavare e sfogliare gli strati di tempo per immaginarsela “com’era una volta”, e poi rimetterli a posto in ordine, strato dopo strato di storia, distruzioni, costruzioni, idee buone, idee pessime, uno sopra all’altro. In questo modo si può iniziare a capire perché si sta vedendo quello che si vede. Una sfida enorme e bellissima. A Manhattan, se si sfogliano poche centinaia di anni – solo poche centinaia di anni – si resta con niente: un’isola, in una tranquilla baia dell’oceano, coperta di alberi e con qualche roccia che spunta qua e là. Non si può incominciare così. Bisogna invece usare i propri sensi, assorbire e memorizzare tutto quello che si può. Bisogna spiegarsi la città a partire da quello che si vede, non da quello che si sa. Manhattan è il risultato dell’oggi, non di ieri o dell’altro ieri. Quando penso a Manhattan oggi mi viene in mente la Venezia del tardo Medioevo e del Rinascimento. Venezia era allora al culmine del suo sviluppo, della sua produzione culturale e della sua solitudine – senza quasi legami con la terraferma e con lo sguardo rivolto ad altri mondi.

***

Manhattan ha messo alla prova tutte le mie aspettative. Rimanevo senza fiato per le dimensioni di alcuni edifici, ma venivo poi rassicurato dal delicato disegno di altri. Ero stupito dalla densità di alcune zone e placato dall’apertura di altre. Quando pensavo di essere nel cuore della città americana per eccellenza, mi accorgevo all’improvviso che per altri aspetti mi sembrava di essere in una città medievale europea: una città che ha ancora confini chiari, demarcazioni, soglie. Oggi la maggior parte delle città antiche è stata fagocitata dai suoi dintorni, dalle sue periferie; città rimaste soffocate dalla loro stessa crescita e che hanno così perso completamente le loro soglie. Avvicinandosi alla parte più antica, il centro, bisogna attraversare zone recenti, meno recenti, quasi vecchie, vecchie e più vecchie, finché finalmente si vede (e si sente) che si sta tornando indietro nel tempo. Il tempo, in questi casi, non lavora solo in verticale, come nell’archeologia (alto = più recente; basso = più antico), ma anche in orizzontale.

Com’è bello invece sapere che si entra in un posto, o che lo si lascia, o che si è appena attraversato un fiume, o il ponte levatoio di un castello, difeso e accogliente allo stesso tempo. Questo è quello che si prova visitando una città medievale perfettamente conservata. La si vede sola in mezzo al paesaggio, la si individua da lontano e ci si dice: “Ah, eccola!”. (È una cosa molto importante: riconoscere qualcosa da lontano per potersi preparare all’incontro.) Ci si avvicina, si incominciano a notare i dettagli, a identificare una torre civica e un campanile, la chiesa più importante, forse una cattedrale. Un’idea di quello che si vedrà all’interno delle sue mura incomincia a formarcisi in testa.

Ecco, Manhattan è proprio così. Se ci si avvicina da terra, la si vede da lontano, da molto lontano. Quando le si arriva più vicino, le diverse parti della città prendono forma: si riconoscono alcuni edifici e li si può usare per ricostruire la propria mappa mentale della città. Ben poco sembra avere senso, se è la prima volta. Se è la cinquantesima volta, ci si incomincia a sentire di nuovo a casa. Si sa che bisogna attraversare un ponte per arrivare, o tuffarsi sott’acqua per riemergere dall’altra parte, e si sa anche che, al crescere della densità, crescerà l’energia, e una volta dentro il resto del mondo resterà fuori.

***

C’è un’altra cosa curiosa di Manhattan, o meglio la cosa curiosa: il centro, il baricentro dell’isola, che in tutte le grandi città storiche dell’Europa è la parte più antica e affollata, a Manhattan è semplicemente vuoto. È vuoto grazie a una insolita decisione presa quando l’espansione e la corsa allo sviluppo erano ancora arrestabili. Probabilmente è stata l’unica occasione che questa città abbia mai avuto di scavarsi un enorme rettangolo nel proprio tessuto – nel proprio corpo e meccanismo destinato a produrre ricchezza – e arrestare ogni tipo di costruzione ai suoi margini. Non riesco a immaginare una scelta più coraggiosa e lungimirante nel progettare l’espansione di una città. Oggi Central Park è uno degli aspetti che rendono Manhattan unica. Vuoi uscire dalla città? Entra. Vai dentro, non fuori, e ti troverai in campagna, con la città tutt’intorno, che ti guarda silenziosa, come un cane ben educato che aspetta pazientemente fuori del negozio il ritorno del suo padrone. Sì, è proprio questo che fa la città: si ferma e dice: “Spiacente, io non posso entrare, aspetto qui, tu vai pure”. Quando si entra nel parco, si sente sempre la presenza della città, quasi il suo desiderio di sapere dove sei, e viceversa. C’è una sensazione di mutua e sottintesa fiducia: una città paziente che aspetta il tuo ritorno.

Dall’esterno dell’isola – dai fiumi che la circondano o dagli altri quartieri – non si immagina l’esistenza di un simile spazio aperto all’interno di quell’ammasso di edifici. E viceversa: da dentro al parco il confine esterno è invisibile; non esiste. La città è come una ciambella, e l’unico modo per poter vedere il buco e insieme la circonferenza è dall’alto. Non sono fatti per coesistere nello stesso campo percettivo, eppure si completano perfettamente a vicenda.

Storicamente, la città ha sempre dato le spalle all’acqua. L’acqua non è mai stata vista come una via di fuga, anzi: come un posto da cui fuggire. I bordi dell’isola ospitavano servizi, attività e un tipo di vita che bisognava lasciare ai margini. (Pensate solo a Tudor City, un intero quartiere costruito senza finestre affacciate sull’acqua, per evitare la vista dei macelli lungo l’East River.) Per uscire fuori, la città poteva guardare solo in un’altra direzione: verso il parco, il vero spazio aperto. Al centro, proprio nel suo cuore.

***

Ho appena finito di lavorare al Guggenheim Museum, il che significa che ho appena superato l’88ma Strada e la Fifth Avenue, diretto verso sud. È il primo importante monumento che ho disegnato da quando ho incominciato questo progetto.

I monumenti ci toccano in molti modi. Li conosciamo perché, per una ragione o per l’altra, sono entrati a far parte di un repertorio comune di immagini, di ricordi, di foto di famiglia. Ogni cultura ha le proprie foto di famiglia, ma ci sono luoghi che appartengono a un album di fotografie “universale”. New York è molto presente in questo album, e giustamente – in alcuni casi si tratta di singoli edifici, in altri di panorami colti da un punto di vista particolare. Quando vediamo uno di questi luoghi o uno di questi edifici noi reagiamo, perché riconosciamo qualcosa. Ma riconoscere è ben diverso da vedere. Quando riconosciamo, diventiamo praticamente ciechi e la nostra capacità di godere innocentemente di ciò che vediamo scompare. Conoscere diventa un ostacolo, non un vantaggio. Quando si guarda il Guggenheim, non è possibile non riconoscerlo. In questo disegno il mio scopo è guardare il Guggenheim (o un qualsiasi altro monumento o vista famosa) e cercare di non riconoscerlo – guardarlo e disegnarlo nello stesso modo in cui guardo e disegno, per esempio, l’edificio che si trova proprio di fronte al Guggenheim, sull’altro lato della strada. Quel palazzo bianco non è citato in nessuna guida turistica di New York (anche se compare in alcune foto del museo), ma per comprendere le emozioni suscitate dal Guggenheim bisogna includere i dintorni, bisogna avere un’idea del contesto in cui si trova.

***

Arrivato a metà strada del disegno, non riesco più a distinguere una sessione dall’altra. La quantità di lavoro, accumulata giorno dopo giorno, fa sì che diventi una cosa sola, un unico prodotto. Il disegno stesso sta prendendo vita e mi lascia libero di commettere degli errori.

All’inizio di un progetto, quando si hanno davanti tutte le possibilità, una svolta sbagliata al primo incrocio può portare lontani dalla meta. Ma quando, per istinto o per fortuna, si incominciano a scegliere le strade giuste (anche se solo più tardi si saprà che sono quelle giuste), gli errori vengono assorbiti e corretti dal meccanismo che si è venuto creando giorno dopo giorno. Ero molto più ansioso, e la mia mano era molto meno sicura, durante i primi centimetri del disegno, quando un grave errore avrebbe provocato in apparenza solo una piccola perdita, visto che avrei potuto facilmente ricominciare da capo. Non ci si rende conto subito di questa nuova libertà, finché non si ha l’impressione di camminare in compagnia di qualcuno, e questo qualcuno è il tuo lavoro.

***

Alcuni anni fa feci un viaggio in moto in Tunisia con un mio amico. Lasciammo l’Italia con l’idea di andare il più a sud possibile, e magari arrivare fino al deserto del Sahara. Durante il viaggio, nel sud della Tunisia, giungemmo all’immenso lago salato prosciugato chiamato Chott el-Djerid e discutemmo se attraversarlo o aggirarlo. Il lago è tagliato da un’unica strada completamente diritta (e dico diritta) di 90 km, chiaramente disegnata sulla mappa con un righello e costruita di conseguenza. Naturalmente decidemmo di attraversarlo.

Ci fermammo per fare benzina e comprare qualcosa da mangiare in una cittadina ai margini del lago prosciugato e ripartimmo a metà pomeriggio. Eravamo abituati alle strade e alle distanze europee, a un certo tipo di paesaggio e al fatto che dopo un pezzo di strada rettilinea di solito si trova una curva, un cambiamento. Di solito. I nostri viaggi precedenti erano scanditi dalla varietà, e non immaginavamo che a un certo momento di un viaggio si possa pensare: “Questo dovrà finire, prima o poi – deve finire”. La distanza è qualcosa di soggettivo, non di oggettivo, e tanto o poco dipende da ciò a cui si è abituati. Ma, per ore, il paesaggio lunare che subito incontrammo non cambiò. I primi chilometri avevano un che di interessante. C’era sempre la possibilità di girare e tornare indietro, e questo in qualche modo ci rassicurava. Ma ben presto i minuti incominciarono a dilatarsi, mentre il paesaggio restava immutabile, fisso davanti, intorno e dietro di noi. Cosa stava succedendo? La strada non presentava alcuna difficoltà, poiché – come mostrava chiaramente la mappa – non c’erano curve né variazioni di nessun tipo. Il nostro desiderio di raggiungere l’altro lato ben presto diventò irragionevolmente pressante, cosicché la nostra traversata si fece prima poco piacevole, poi realmente difficile. Durante i primi chilometri, ogni sensazione, del luogo, della velocità, dello spazio intorno a noi, ci pareva in qualche modo estranea. Poi, man mano che i chilometri si accumulavano, quella stessa sensazione lentamente divenne parte di noi. A un certo punto capimmo che eravamo vicini o avevamo già superato la metà della traversata, per cui non aveva senso tornare indietro. Invece di doverci spronare a continuare, adesso eravamo attirati dalla fine della strada di fronte a noi. Il peso aveva lasciato il posto alla leggerezza.

Tutt’intorno a noi c’era un paesaggio di sabbia polverosa e salata. Le nostre ombre diventavano sempre più lunghe. Viaggiare in moto significa che fra te e il paesaggio non c’è nulla. Tu sei il paesaggio.

Avvicinandoci all’altra sponda, la fine della strada ci attirava con sempre maggior forza. Volevamo andare più veloci, ma nello stesso tempo cominciavamo a desiderare che il viaggio si prolungasse. Iniziavamo a rimpiangere quella condizione di sospensione del tempo ancor prima che finisse. Quando arrivammo dall’altra parte, la luce del giorno era quasi svanita. A ovest, le montagne che circondavano il lago prosciugato si stagliavano blu sul tramonto, mentre le montagne di fronte al sole calante erano di un rosso vivo.

Non esiste una cosa come una semplice strada diritta di 90 km. Ogni chilometro ha un sapore diverso; ti spinge, ti attira, ti ipnotizza o ti spaventa.

***

L’unico modo per restare fedele al mio progetto apparentemente oggettivo (“disegnare tutti gli edifici che si affacciano sul parco”) è di essere totalmente soggettivo. Il punto di vista cambia ogni pochi isolati; si muove man mano che ci spostiamo lungo il perimetro del parco. L’unico modo per congiungere due di questi punti di vista è una piccola bugia: devo mostrare due facciate di edifici adiacenti che non sono mai visibili nello stesso istante. Ogni edificio ha anche un lato privilegiato, un punto di osservazione migliore per guardarlo e capirlo (gli edifici, in questo, assomigliano molto alle persone).

La serie di bugie necessarie per sistemare le prospettive e i punti di vista funziona come della calce per i pezzi del disegno. Li tiene insieme, li rende una cosa unica.

***

Mi sto avvicinando alla 59ma Strada. Finora il punto di vista si è spostato lungo la Fifth Avenue, parallelo alle facciate degli edifici che danno sul parco. Si è fermato ogni tanto per consentire alla prospettiva di centrarsi su alcune strade, ma ha proceduto abbastanza regolarmente. Adesso, avvicinandomi all’angolo sud-ovest del parco, il punto di vista deve rallentare, poi fermarsi e ruotare allo stesso tempo, fino a volgersi verso Central Park South. Se dovessi prendere i quattro lati del parco e semplicemente metterli insieme, ignorerei la città che vedo guardando dritto verso l’angolo, e perderei completamente la densità a sud-est e a sud-ovest del parco.

Una volta che il punto di vista avrà completato la sua rotazione e sarà rivolto verso Central Park South, potrà continuare verso ovest, verso Columbus Circle.

***

Gli edifici lungo Central Park South e quelli alle loro spalle sembrano voler saltare nel disegno. È difficile scegliere quali disegnare e quali trascurare, perché mi chiamano, si vogliono far vedere, mi fanno cenno da lontano, “Ehi, e io? Non vuoi mettermi nel disegno? Ma stai scherzando?”.

Creare una prospettiva per questo pezzo è più difficile, molto più difficile di quanto immaginassi. Central Park South non è molto lunga, per cui non ha senso continuare a cambiare punto di vista. Ciò creerebbe inoltre troppi spazi vuoti (i vuoti prodotti dalla giuntura fra due punti di vista diversi) e l’impressione creata dall’incredibile ammasso di edifici si perderebbe. Quindi l’unico punto di vista sarà al centro, fra la Sixth e la Seventh Avenue. Da lì mi volterò prima verso est e poi verso ovest per creare una sola immagine dei tre lunghi isolati di Central Park South.

***

L’architettura non sta ferma ma si muove. Non è necessario guardarla per poterla percepire. È percepita dai nostri sensi in ogni momento. Quando ci facciamo i fatti nostri, l’architettura si muove intorno a noi; i palazzi danzano e ruotano e si chinano e si confondono l’uno con l’altro. Percepiamo le loro dimensioni e le loro varie facce in movimento. Assorbiamo tutto questo inconsciamente, del tutto inconsapevoli di essere noi fermi in un mondo di masse in movimento.

Quando la guardiamo intenzionalmente, l’architettura allora si ferma. Guardiamo i dettagli, le proporzioni, i colori, le forme, e ricostruiamo tutto questo nel nostro cervello perché “vogliamo capire”. Trasformiamo un’esperienza sensoriale in un’esperienza intellettuale.

Gli edifici ci parlano. Parlano di emozioni e ricordi. Ci raccontano qualcosa del tempo in cui furono progettati e costruiti, dei materiali usati e della scelta dei dettagli, o della loro assenza. A New York quasi ogni edificio parla un proprio linguaggio. E nel parco, dal parco, questa relazione – il dialogo fra i nostri sensi e le migliaia di linguaggi della città – è sorprendentemente chiara. È chiara perché siamo lontani quanto basta per sentire tutte quelle voci fondersi in una sola.

***

Dopo il rumore di Central Park South, non è facile tornare a un ritmo più equilibrato e tranquillo. Gli edifici lungo Central Park West respirano meglio; hanno abbondanza di aria e di spazio intorno a sé. I palazzi con due torri (il Century, il Majestic, il San Remo, l’Eldorado) sono distanti l’uno dall’altro e dominano lo skyline. Molti palazzi art-déco salgono con calma finché raggiungono il quattordicesimo o il quindicesimo piano, poi (come quello all’angolo della 66ma Strada) esplodono in un groviglio di dettagli e decorazioni; diventano improvvisamente castelli di sabbia iper-decorati. Il Majestic, con i suoi costoloni verticali, sembra emergere direttamente dal sottosuolo. Altri (come il Dakota o il St. Urban) sembrano provenire da altre città e da altre epoche. Questi edifici non danno l’impressione di essere sospinti da una grande massa alle loro spalle. Non devono lottare per farsi vedere, o per godersi la vista: stanno semplicemente lì, orgogliosi, davanti al parco.

***

La città sta al parco come un ciclone sta al suo occhio: non c’è vento, non c’è energia nell’occhio del ciclone, solo intorno ad esso. La forza centrifuga della tempesta apre il suo centro, il silenzio sembra irreale, il cielo è limpido, la città resta fuori.

***

Il sistema della griglia stradale ortogonale è un meccanismo molto utile. Quando mi trasferii a New York, mi ci volle solo un giorno per imparare come e in quanto tempo potevo andare in un posto qualsiasi. (A parte downtown, naturalmente, dove mi sentivo a casa in altro modo, a causa delle sue strade strette e tortuose.) Il sistema della griglia ti permette di capire Manhattan istantaneamente. Ti permette di localizzare il punto A e il punto B, poi di collegarli e di valutare la distanza, il tempo e lo sforzo fisico necessari per andare dall’uno all’altro. La comprensione di una città europea, invece, si basa sulla conoscenza degli itinerari. Sapere la posizione dei punti A e B spesso non è sufficiente per visualizzare e valutare il percorso reale. Bisogna conoscere un certo numero di itinerari prestabiliti che collegano le diverse zone della città, in modo da poter cercare i punti precisi all’interno di quelle zone.

***

Qualche settimana appena passata in Italia, a risentire odori familiari, a vedere immagini di antiche città e a percepire tempo accumulatosi su pietre, mura e palazzi. Qualche settimana passata ad Ascoli Piceno, città di origine della mia famiglia, il cui centro è un antico, denso agglomerato di edifici dell’epoca romana, medievale e rinascimentale, che proteggono una piazza incredibile, uno spazio aperto completamente rivestito con lo stesso travertino di cui sono fatti tutti gli edifici. Piazza del Popolo ti si apre davanti mentre passeggi, all’improvviso, e ti mostra uno spazio aperto rettangolare, lastricato e circondato da portici, dal palazzo municipale medievale (Palazzo del Popolo) e dal fianco (non dalla facciata!) della basilica più importante (San Francesco). È spettacolare e rassicurante nello stesso tempo.

Ad Ascoli, i miei pensieri sono tornati rapidamente a Manhattan e alla sua preziosa apertura, Central Park, la cui pavimentazione è fatta di erba e il cui colonnato è fatto di alberi e magnifici edifici, tutti diversi l’uno dall’altro, separati ritmicamente dalle strade della griglia. Variano in altezza, materiale, peso e carattere, ma tutti si affacciano sul parco, come se guardassero rispettosamente la piazza principale della città.

***

Sembra che tutti noi che veniamo a New York da qualche altra parte vogliamo conoscerla, e conoscerla a modo nostro. Vogliamo scoprire cose che nessuno ha scoperto prima, o che sono state in qualche modo trascurate. E vogliamo capire perché è così bella, e intensa, e da dove viene la sua energia. Noi (che veniamo da altrove) ci mettiamo un po’ ad accettare il fatto che un posto in evoluzione raramente si lascia spiegare, perché non è mai finito. Semplicemente ha bisogno della tua vita – la tua energia – che poi diventa parte dell’“energia della città”.

La complessità e la ricchezza della città sono i segni della sua continua trasformazione: quartieri che si spostano e cambiano nel giro di pochi anni, edifici che vengono sostituiti con altri e continuamente ricostruiti, un nuovo palazzo che sorge a ogni angolo. Ci vuole energia per tenere il passo del cambiamento. Scordati di capire il perché.

***

È l’inizio dell’autunno. Nel parco. Il sole è appena calato oltre l’orizzonte, nel New Jersey, e la sua luce sta svanendo a poco a poco. In questo momento fugace, il mio affetto per la città è al culmine. È durante questa transizione che la città appare umana e vulnerabile. Gli uccelli del parco sono ormai quasi completamente in silenzio; le finestre degli edifici rivolti a ovest (lungo la Fifth Avenue) si illuminano e scintillano negli ultimi istanti di luce naturale. Le luci all’interno degli edifici si accendono poco per volta, ma non si capisce se quello che si vede dipende dalla luce artificiale o dal riflesso, perché i riflessi, in questo istante, appaiono luminosi come le luci all’interno. È come se le ultime scintille di luce naturale fossero rimaste intrappolate dentro gli edifici.

Mi giro dall’altra parte (verso Central Park West) e guardo gli edifici rivolti a est: il sole, dietro di loro, è scomparso e tutti i colori del tramonto disegnano lo sfondo della loro silhouette. Gli edifici sembrano incisi nel cielo, completamente privi di volume. Le luci all’interno vengono accese, poco per volta, qua e là, a caso, ma non sembrano altrettanto brillanti, a causa dell’effetto abbagliante dello sfondo. Sono queste luci che ridanno profondità agli edifici.

Un vento fresco si leva dal parco e mi immagino che sia il respiro di tutti i volumi che reagiscono, all’avvicinarsi del buio, espandendosi e contraendosi.

***

La radio ci ha avvertiti stamattina che la tempesta di neve che sta per abbattersi su New York oggi si estenderà su un terzo degli Stati Uniti. Una tempesta di queste dimensioni è insolita per l’inizio di dicembre. In genere si verifica più in là, a gennaio o a febbraio.

Ero al parco stamattina e mi godevo la vista della neve che cadeva e ascoltavo il suono – tic, tic, tic – che fa quando colpisce le poche, indurite foglie superstiti. Nel North Meadow, lungo il confine nord, scorgo un tizio che cammina fra i cespugli. Quando mi vede, corre fuori e mi chiede con un forte accento (credo dell’Australia o della Nuova Zelanda, non ne sono sicuro): “Dov’è il sud?” A una domanda così semplice e diretta, io rispondo allungando il braccio nella direzione giusta, cioè verso Central Park South, un po’ inclinato verso l’hotel Plaza. Il tizio mi ringrazia e incomincia a camminare, ma dopo un paio di passi si ferma e mi chiede (e stavolta il suo accento è talmente forte che devo chiedergli, col mio di accento, di ripetere quello che ha appena detto): “Come si fa a uscire di qui? Voglio dire, bisogna conoscere tutti i sentieri di questo posto o c’è un altro modo?” Era incredibile, ma stava mettendo il dito proprio su una delle questioni che andavo rimuginando da qualche mese. Ero pronto a sostenere una lunga discussione filosofica sull’idea di essere fuori della città, anziché “intrappolato” al suo interno, come sottintendeva lui. La sua domanda chiariva il paradosso del rapporto fra il parco e la città: aveva creduto di entrare in un famosissimo parco, e invece si era trovato fuori città, perduto, come in una fiaba. Il che era vero soprattutto questa mattina, quando di Manhattan si riusciva a vedere solo il vago contorno grigio degli edifici contro un cielo e un terreno lattiginosi, tutti dello stesso colore. Mi divertì che mi chiedesse come “uscire” di lì, quando in realtà sperava, anche con una certa ansia, di “rientrare” in città. Invece di annoiarlo con tutto questo, gli dissi semplicemente che sì, si potevano studiare tutti i sentieri, ma il modo più semplice, per me, era quello di usare gli edifici intorno al parco come punto di riferimento per sapere la propria posizione.

***

L’aspetto di tecnica esattezza che volevo a tutti i costi evitare – ebbene, l’ho evitato. La linea degli alberi è gradualmente scesa verso il basso del foglio, un fatto che noto solo adesso, al momento di disegnare il secondo dei due edifici a torre all’angolo fra Central Park West e Central Park North. Avevo disegnato quello sul lato nord all’inizio del lavoro e adesso, che sono alla fine del disegno, devo disegnare quello sul lato sud. Volevo assicurarmi che quest’ultimo edificio fosse, sulla carta, alla stessa altezza. Ho srotolato il disegno fino all’inizio e ho preso un pezzo di carta da schizzi per ricalcare i primi centimetri del disegno. Poi ho riarrotolato tutto il disegno fino alla fine e l’ho sovrapposto allo schizzo. Ebbene, non corrisponde. La fine del disegno è considerevolmente più in basso dell’inizio. Non ho molto spazio per correggere (cinque o sei isolati), ma per fortuna qui nel parco c’è la Great Hill. La Great Hill è abbastanza alta e impedisce la vista di molti degli edifici bassi su Central Park West e la 107ma, 108ma, 109ma Strada. Usando la collina, posso alzare la base verde e sistemare l’ultimo edificio, “Towers on the Park” (Sud), più o meno dove dovrebbe essere, di fronte al suo gemello sull’altro lato della strada.

***

Mi mancano pochi centimetri; è arrivata la fine del lavoro. La aspettavo da tanto tempo, ma adesso non vorrei davvero vederla. Sento l’odore del legno del rocchetto di destra. Su quello di sinistra c’è uno spesso rotolo di carta. Sembra più vecchio adesso. È pieno di colori, di linee, di dettagli di tutti gli edifici che ho disegnato.

***

Per disegnare l’ultimo angolo, fra Central Park West e Central Park North, devo usare le prime foto, fatte un anno fa. Guardo lo stesso angolo 9 metri e 75 centimetri, 624 edifici e 35.842 finestre dopo. Mentre svolgo il disegno, gli edifici mi passano davanti. Vedo le molte sessioni che adesso sono una sola, i giunti senza giunture. Rivivo tutte le scelte, quale lato di un edificio mostrare, come svoltare un angolo, dove collocare un punto di vista. La fine mi ha riportato al principio, ma quest’ultima giuntura – la giuntura del tempo – non resterà invisibile. Quest’angolo, per me, non è più lo stesso posto.

1 marzo 2002 – 24 febbraio 2003

Traduzione dall’inglese di Alberto Cristofori