Saul Steinberg: the legacy of a genius

by Matteo Pericoli

Published in the March 2022 issue of L’Indice dei libri del mese

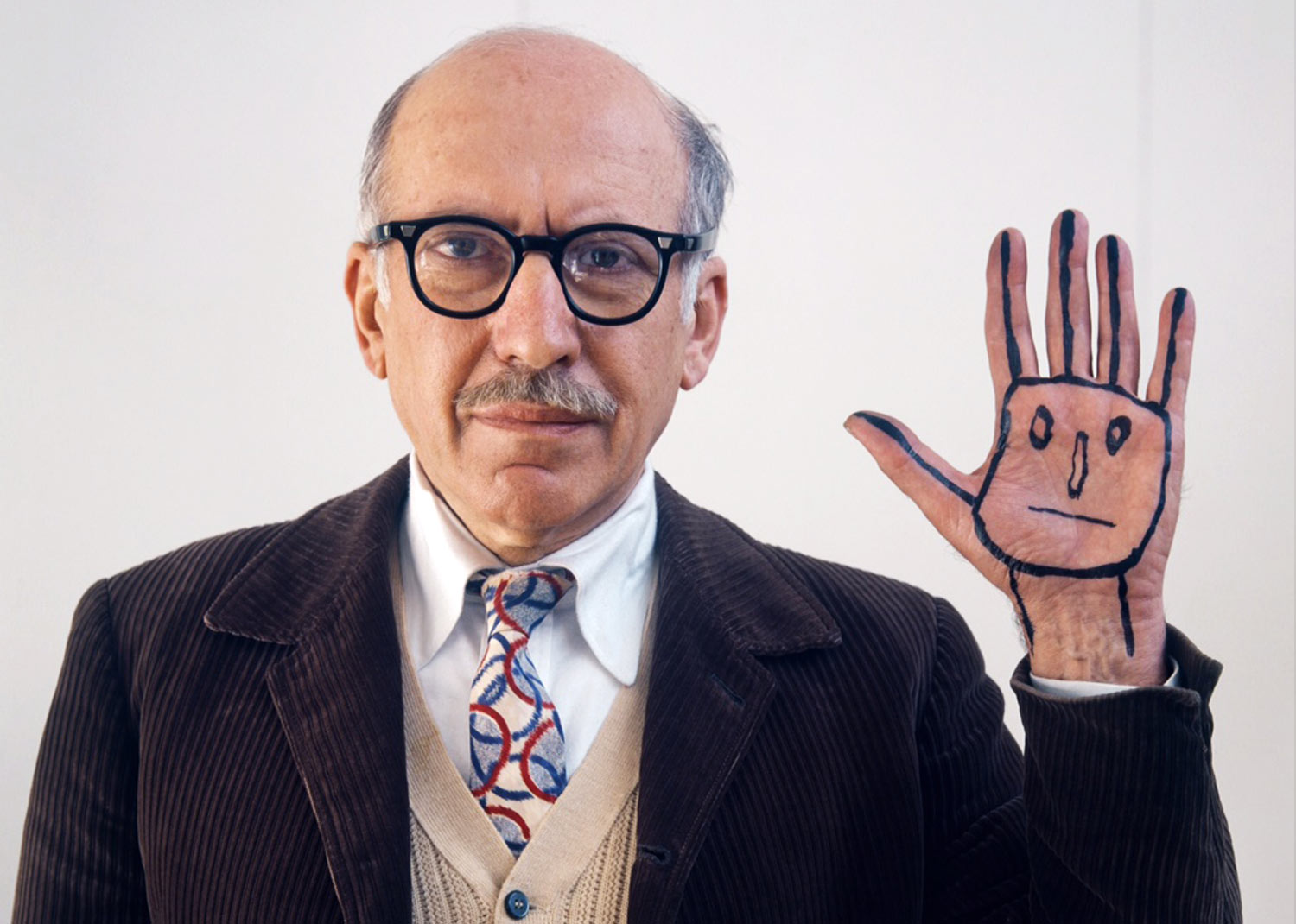

Saul Steinberg 1978. Photo by Evelyn Hofer

One of the greatest challenges we encounter when trying to interpret Saul Steinberg’s work is trying to find the right angle of approach. The typical mistake we often make is trying to classify him: Is he an illustrator? No, or maybe yes; Is he a cartoonist? Sure! No, of course not; A brilliant draftsman? Yes, a draftsman for sure, or maybe not? Is he perhaps more simply, or more generically, an “artist”? Well, that’s a given. However, as we carefully approach the complex figure of Saul Steinberg it feels as if not even the all-encompassing word “artist” is accurate enough. He was not just an artist; he was something more. But what?

Steinberg was born into a Jewish family in Romania in 1914. He lived in Bucharest until 1933 when he moved to Milan, Italy, where he studied architecture at the Regio Politecnico. Within a few years he began to publish drawings in various Italian magazines and enjoy a certain success. Yet, his situation got complicated by the racial laws, so much so that as soon as Italy entered the war he decided to immigrate to the United States. However, he was arrested before he could leave and spent a period of several months of internment in Abruzzo. In the summer of 1942 he finally managed to arrive in New York.

Steinberg’s work at that point was already well-known in the United States. In fact, thanks to several acquaintances, in the period right before entering the country he had already published many drawings in various American magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar and Life. Upon his arrival in New York, Steinberg started practically immediately to collaborate with The New Yorker magazine, contributing covers, illustrations, drawings, cartoons and so on — something he would continue to do, with exceptional and perhaps unparalleled success and freedom, for the rest of his life.

Many clues to the difficulties in describing him are found in quotes from Steinberg himself, such as: “I was born in a complicated country, one had to pave one’s own’s way through several contradictory truths, a magnificent school for a novelist. The only characters I respected, the only ones I could converse with, were characters from novels. I believed that books were of divine origin, and when I realized that they were written by ordinary people (who were therefore unknown before they became famous), I was so impressed that I said to myself, ‘Then I can do it too!’” (Riga, p. 111)

However, his conflictual relationship with Romania, the “infernal homeland” (Lettere a Aldo Buzzi, p. 278), his betrayal by Italy and its racial laws, and his being an immigrant, albeit a naturalized one, in the United States meant that Steinberg lacked a language with which he could express himself with total ease and with the same familiarity of the novels he adored.

In an incessant search for himself, his identity, and a language of his own through his work, Steinberg sought on the one hand to define himself, find himself, know himself, and make himself known, while on the other hand simultaneously create and erase any traces and images of himself.

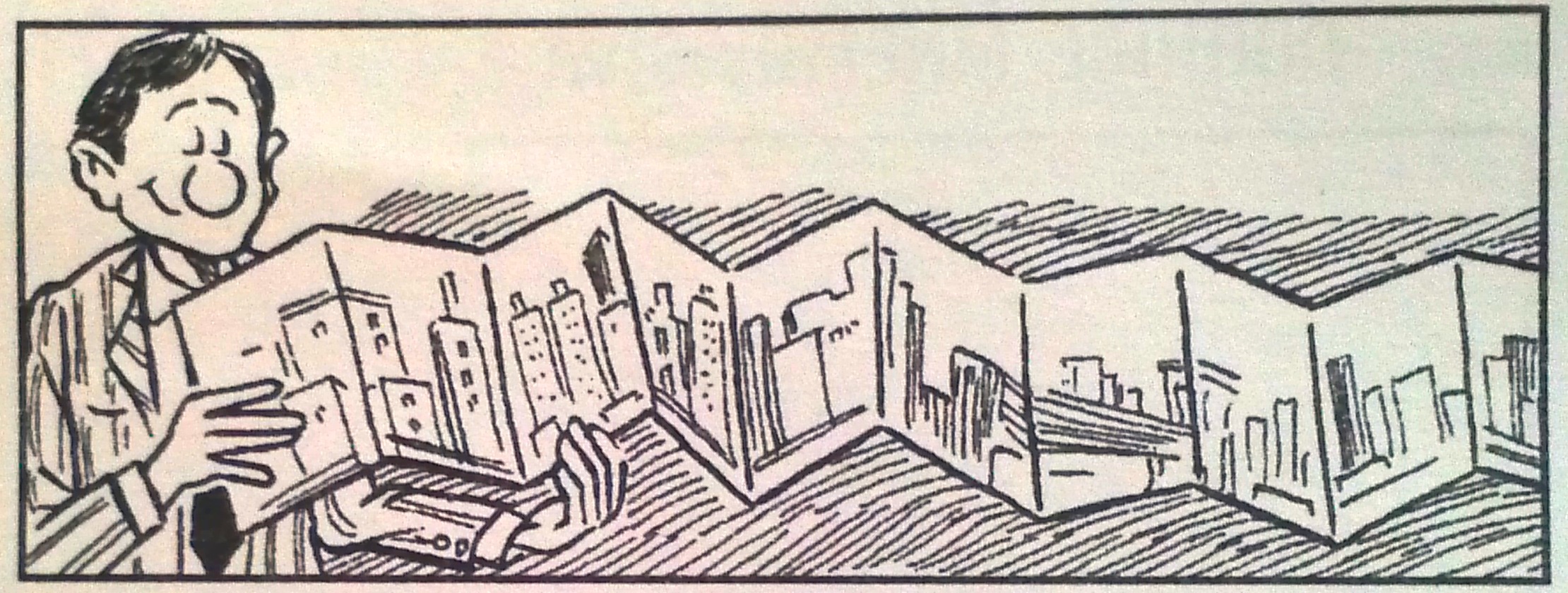

It was Steinberg himself who recounted how in the midst of this dogged research he ended up inventing “a language that did not exist before as a language.” He chose a “raw material,” i.e., drawing, and used it “to express his poetic or philosophical ideas” (Riga, p. 106). It was not the kind of drawing that comes from the tradition of life drawing, because, as Steinberg said, “life drawing reveals too much about me […] I become a kind of servant, a second-rate character” in which “I see […] my own defects.” In drawings “made from imagination,” however, Steinberg could both hide himself and introduce multiple levels of reading and interpreting his work: “I show myself and my world in the way I choose.” (Riflessi e ombre, p. 59)

And so we, the viewers, through his work, do not have access (as is usually the case) to what Steinberg “sees” as he draws; rather, we are faced with an open window into his mind and thoughts, as in a literary text or essay or treatise.

In all of this I think architecture played a very significant, albeit indirect, role. Steinberg said that the study of architecture was for him “wonderful for everything but architecture. The frightening thought that what you draw can turn into a building makes you lean toward perfectly reasoned lines.” (Riga, p. 38) His lines then, so reasoned, precise, and with crystal clear intent, are the visible imprints of his intuitions, thoughts, and reasoning.

But not only that. Just like the greatest architects, Steinberg even seemed to know what we, in turn, think or know. In fact, his drawings remind me of the Parthenon in Athens. In wanting to convey a sense of harmony, proportion and clarity, the builders of the Parthenon knew that our minds correct, modify and see in a distorted way. For example, they knew that the columns at the edges should be slightly enlarged and pushed a little closer to the others, otherwise they would risk appearing farther apart and smaller than the others; or that the base of the tympanum should be slightly curved downwards, otherwise its ends would give the impression of turning up instead of appearing horizontal. Therefore, the relationship that is established between those who build and those who absorb (in this case, an architectural space) is a sort of interconnection or collaborative effort between two creative sources: that of the designer and that of the viewer.

It is not by chance that the philosophers Roberto Casati and Achille Varzi wrote that “commenting on a drawing by Steinberg is […] like commenting on the work of a colleague” (Riga p. 398). Non only did Steinberg want and know how to speak to everybody, he wanted to be heard by everybody too.

To better approach his work, we therefore have no choice but to linger in front of his drawings, resist the desire to classify him, let his lines seep into our minds and land in his fantastic world.

— March 2022

Books quoted (citations translated by me):

Riga 24, Saul Steinberg, Marcos y Marcos (Italy, 2005)

Saul Steinberg, Lettere a Aldo Buzzi 1945-1999, Adelphi (Italy, 2002)

Saul Steinberg con Aldo Buzzi, Riflessi e ombre, Adelphi (Italy, 2001)