An essay by Colum McCann published in World Unfurled by Matteo Pericoli

(Chronicle Books, 2008)

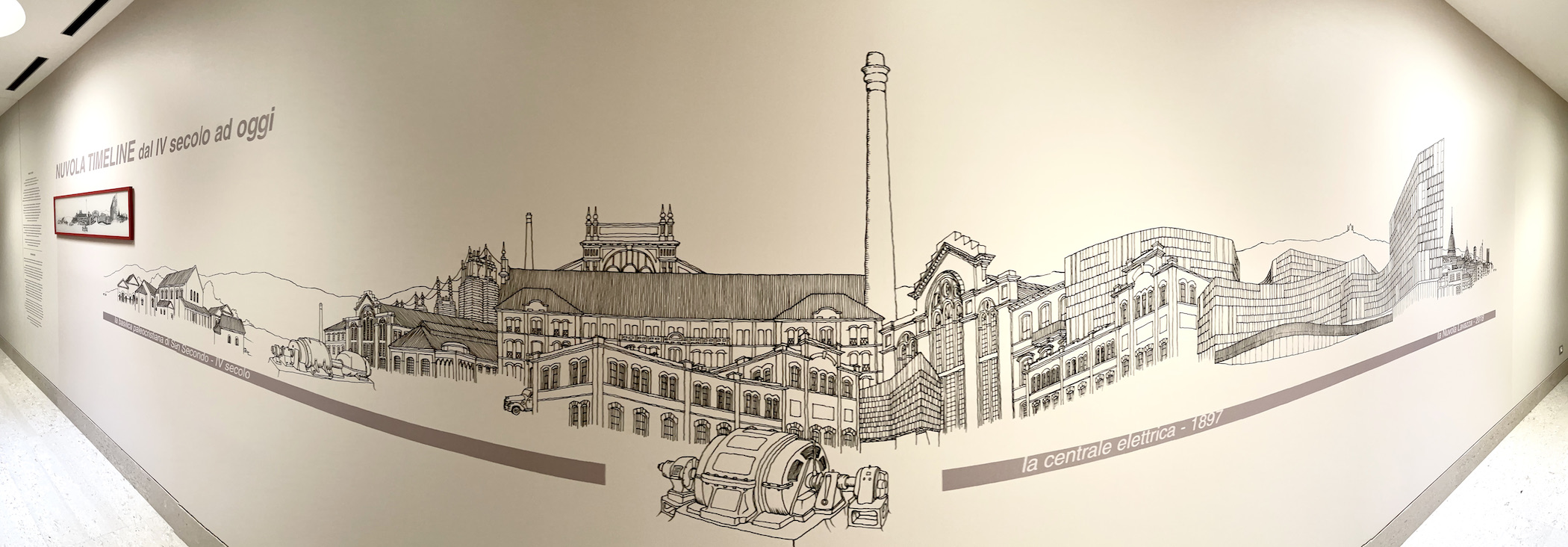

The American Airlines mural by Matteo Pericoli at JFK International Airport in NY (Photo by Richard Slattery, May 2007)

We leave: it’s inevitable. We sometimes come home: that’s our choice. In the process, we can bring our home country to another land, or we can cart that other, distant country back toward our own and sometimes make it new. And so, every building we have walked through begins to walk through other buildings. Every city skyline we see is informed by the skylines we have glimpsed before. All that we have met meets all that we will meet.

We are connected and remade by what we have seen.

I grew up in suburban Dublin, Ireland. I can still hear the ticking of the white radiators. The back door slammed when the front door opened. A house of open windows, I was always flying out of them.

I first left home when I was seventeen. I went to Mayo, less than one hundred and fifty miles away. The newspaper building where I worked was down a cobbled laneway. I loved the creak of the stairs, and the rattle of the printing presses below. I took the train back to Dublin only once that whole summer. It seemed to me like an enormous journey and I recall how thrillingly new my doorstep felt when I returned: it was like stepping onto brand new territory.

Not long afterward, I broke the border of home again, and went to New York. My heart thumped in my cheap white shirt. I got a job as a cub reporter in the Time Life building and, fired up on innocence and a brash enthusiasm, I ran down Avenue of the Americas, then stopped and lay flat on the ground—for an instant, passersby had to step over me. It was the only way for me to glimpse the panorama. The skyscrapers dizzied me. It seemed impossible that there could only be a small scrape of blue sky. Later that same evening I brushed the dirt off my trousers, ran to catch the D train, got out at Brighton Beach, and rented a tiny room in a clapboard house that smelled of roach spray and sea breeze. I flopped down on the dingy mattress. How, I wondered, could two such diverse settings exist in one city in a single day?

It seemed to me, even then, that sometimes we have to go far away to explore the dynamic possibilities of our own naivety.

A few years later I took a bicycle across the United States. I rode the little blue highways and the back roads. The stars were my ceiling. Camping out, in forests and by riverbeds, I spent eighteen months learning the roof of the world. From there it was on toward Japan. The sun caught the top of a Kyoto shrine. My wife and I rented a six-tatami-mat room. Later we found an apartment in the shadow of a Kyushu mountain. Then it was back to New York once more: countless windows outside our window.

There have been so many places since. The clean steeples of Singapore. A villa in Capri. A wooden hut in Slovakia. A church in Saint Petersburg. The tall pillars of the Brooklyn Bridge, strung with wires like a harpsichord. Some of these places have been the sites of fleeting visits, others are regular haunts. My memory is decorated by a series of mirrors that throw color and sound onto yet other mirrors: these places flash across my mind and collide into each other, touch at odd angles, then mingle and disperse.

It strikes me now that the purpose of remembering—and perhaps even the final purpose of travel—is to depict, and therefore render forever present, that which is absent. We return by leaving. Travel is a process of deep renewal. Every time I go away, I am back on my New York doorstep. Every time I am on my New York doorstep, I am stepping away into all those other places I have gone and will go.

I am a citizen of my own imagined elsewhere.

♦

It is difficult to find a grand public adventure these days. This is both good and bad news. Newspaper editors aren’t really captivated by an eighty-day journey around the world. Scaling the world’s highest mountains is easy enough if you’ve got the money for it. It’s hard to find a place where a foot hasn’t already been placed, a field that hasn’t been trampled. The Earth is as mapped and documented as never before. On the other hand, adventure has become an acutely democratic notion. A lot of us are lucky that the world has shrunk: we can go places our forefathers couldn’t even have dreamed about. But the primary adventure occurs now in our imaginations.

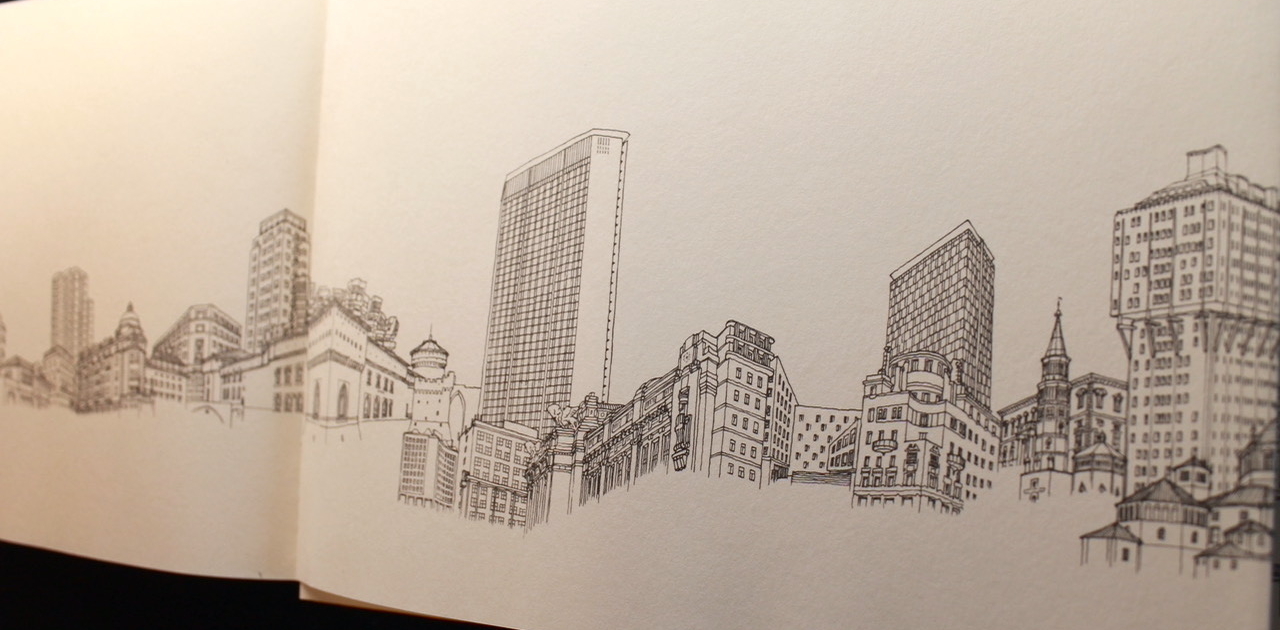

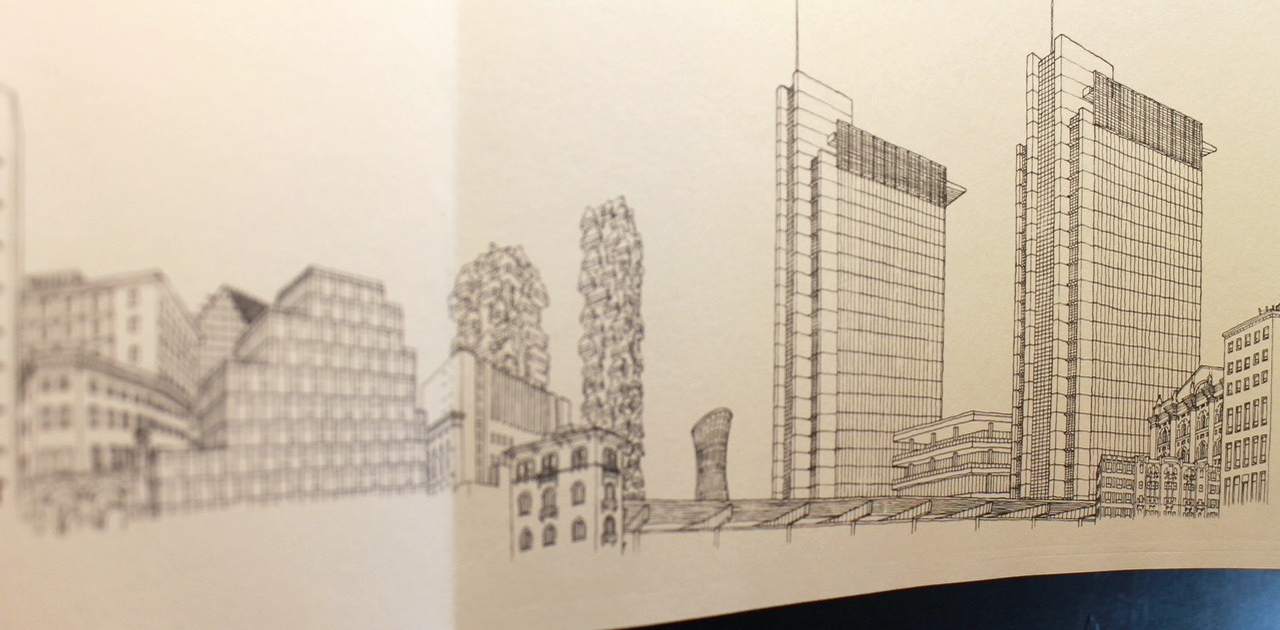

Passing through the automatic doors into the vast white space of Terminal 8 in New York’s John F. Kennedy airport, one is immediately drawn to Matteo Pericoli’s mural, “Skyline of the World.” Here, in a sense, is the beginning of travel. The eye finds no resting place. The mural runs along the swooping roofline, the full length of the eastern wall, a block and a half. It is 52 feet in height, and covers almost 16,000 square feet. A viewer might feel as if he has one foot in the vanished past, the era of high-ceilinged railroad stations, and another foot in the open terminal of tomorrow.

Place and time are bundled together. Seventy cities and four hundred and fifteen buildings merge into one. Each place dissolves into the next. The Sydney Opera House nudges up against Toronto’s City Hall. Stroll down the hill from Los Angeles and you’re standing near the Jantar Mantar Observatory in New Delhi. A canal slips around the Foshay Tower: how is it that the waters of Venice have suddenly migrated to Minneapolis? The Fred and Ginger building in Prague rises up to meet Bangkok. And the Brooklyn Bridge stretches out like a great hand that wants to reach inside your ribcage and twist your heart a few notches backwards.

The content of Pericoli’s work, if I may dare to state it in a single word, is memory. For him, recall is a creative act. He invites us into a landscape in which the viewer can thrust his or her own past, and at the same time he allows us to step beyond the boundaries of our lives. Remembering becomes an act of the imagination, a process without borders or gateposts. Here’s another city—indeed, another country— but we’ve all been there already. Still, it’s a city made entirely new, as if it has gone through the process of radical recycling. There is a sort of madness here too, a shrinking of the world through the marks of a pencil. Perspective is shifted. The geometry is jagged. Yet the drawing maintains a form that we recognize, a series of intimate lines and well-known landmarks that are both stunning and perplexing at the same time.

Pericoli has created a trance city, in hues of gray, blue, orange, and white, built on our own memories of previous travel and expectations for the journeys we are about to embark on.

Fittingly, we don’t always know where we are when we examine it. Walk down off the Brooklyn Bridge and enter the city of Zurich. Turn left and you’re in Kingston, Jamaica. Swivel around and you’re in Bogotá.

Some of the buildings are instantly recognizable despite their jumbled placement, as if a surreal postcard has just landed, undated, on a terminal wall. But others are relatively unknown. Pericoli has even included his grandmother’s house from a small Italian village, and an imaginary building by artist Saul Steinberg.

“A memory of a journey is a memory in which time and space are mixed up,” Pericoli has written. “They both seem to vanish, as distances and places tend to be compressed into a single, intense yet detailed blur. After a trip, the famous landmark you just visited will be imprinted in your brain as much as the undistinguished building you saw from your hotel room window.”

Although the buildings are chosen for their architectural and aesthetic value, there is surely an understated political intent in play: the buildings are placed beside each other almost as if they could—and should—learn from each other. East meets West. South meets North. They learn from one anothers’ curves and angles. They don’t feel forced or sandwiched in. This statement of potential compatibility takes place not only in a geographical context but also in a manner that’s refreshingly anti-chronological: so that the Azadi monument in Tehran, for instance, built in 1971, is in sight of the Kremlin, which dates back to the fourteenth century, which in turn is just down the hill from La Pedrera, the astonishing “sculpture house” created by Antoni Gaudí in 1912, and now designated a World Heritage Site.

This ability to cross through periods of time, and to create a believable international landscape, and then to invite us to inhabit it—and maybe even to re-inhabit it—is something not many artists, let alone politicians, have ever contemplated. Pericoli demonstrates that nothing original is created through predictability. Even cities might want something better than what they already have, a new perspective, a surprising neighbor.

♣

After looking at “Skyline of the World” for a long time, I began to wonder if Dublin might be represented somewhere, tucked away at the edges, or maybe even in the foreground? I recognized a good deal of the landscape. Seattle’s Space Needle. The Empire State Building. The Jubilee Church in Rome. Still, many of the mural’s buildings mystified me. I wanted to peep over the shoulders of the cornicework and discover what was on the other side.

What would happen if my mind were able to pull the drawing apart, allowing me to climb inside?

I found myself walking into the drawing, turning the corner around a mosque toward a citadel, up the street to a glass tower, down an alleyway toward a mysterious house in the shadow of a water tower. Suddenly there were birds and weather and people around me—all things that are absent from the public face of the mural. The further I walked, the more I saw. But so much of the landscape remained foreign to me. On one street, I was lost. On the next I was found. It was like seeing an old friend and then waving good-bye.

And then, suddenly, there was the inner city of Dublin, right in front of Pittsburgh, just next to Valparaiso, on a hill above the Seattle Public Library. I could almost smell the water off the Liffey, see the traffic trundling down along Burgh Quay, hear the hawkers in the alleyways of my youth. I heard footsteps. The opening and closing of doors. I realized then that I am constantly leaving, trying to discover new places, both imaginatively and physically, and yet always coming closer to home.

♠

But let’s face it—even the best airports are exercises in contemporary vulgarity. Travelers are tense. Officials are on edge. Security guards are suspicious. We take off our belts, our shoes, and our jewelry and are shunted through a metal detector. We leave behind water bottles, lighters, key chains. The flight announcements sound out around us. The cell phone user behind us seems to think that “etiquette” is a village in France. The departure screens hold news of delays. We invariably end up in the longest line, listening to inescapable tinny Muzak floating through the air.

At the worst of times, it seems as if there might be no escape. Travelers are locked in. Most airports break up the sight line with ads, or blankness, or a crass nod to the corporation itself. But somehow, when it came to designing the interior of Terminal 8 in JFK—possibly one of the last airports where one might expect it, given the distinct lack of imagination most of the older terminals display—American Airlines managed to avoid slapping its own back. They refused the temptation to even put a plane in the skyline. The terminal itself can be seen in the far left-hand corner, but this seems more like a postmodern wink than an advertisement.

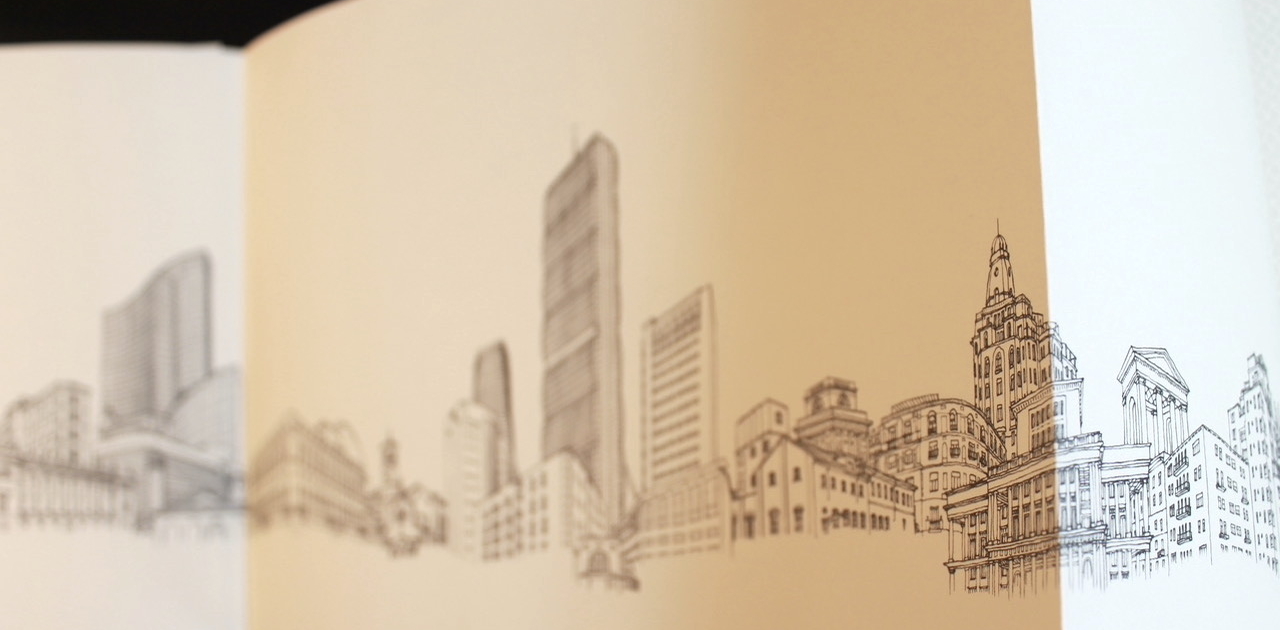

The mural came about through an odd collision of mistakes, reconsiderations and brave imaginative gestures. The terminal was originally supposed to be much larger, but after 9/11 the plans were scaled back and American Airlines were faced with the prospect of a blank wall almost 400 feet long. Airline officials had seen Pericoli’s previous work and they contacted him in January 2005. They wondered if he’d be able to fill the space somehow. Pericoli loved the challenge of combining his architectural background with his artistic instincts. Trawling the Internet and his memory both, Pericoli began to sketch. He assembled photos from cities all around the world and then copied them meticulously into place. His battery-powered pencil sharpener sat at the ready on his desk. He used 2B pencils on vellum, allowing him to excavate the drawing with what he terms “a fresh palette.” He found an order in chaos and beauty. He never once used a ruler. Of course, it would have taken many years to do the drawing directly on to the wall, so instead he toiled at home in Queens on a drawing that was one thirty-second the size of the final mural.

Month after month, his dreamscape grew.

When the drawing was finished, it was sent to Professional Graphics in Illinois, where it was photographed in sections using a Hassleblad camera with a Sinar digital back. The trick was to enlarge the drawing without destroying it. Every inch would be almost three feet high. Suddenly every window ledge had a potential jumper, an art critic at each precipice. If Pericoli had gotten it wrong, they’d leap. But it was here that the artist’s attention to detail paid dividend. Pericoli is, I feel, the sort of artist who could be entrusted with the last grain of sand, perhaps one of the few who’d be able to capture its complexity. With “Skyline of the World,” he was so careful with his pencil work that the intimacy could be blown, quite literally, sky high.

Professional Graphics printed the drawing on almost one hundred vinyl panels, which ranged in height from 30 to 52 feet high. The printing process alone took the better part of ten days. The installation—the application of the massive sheets to the wall of the terminal—took months of planning. Of course, the drawing, as in any good work of art, really took a lifetime.

The mural went up in May 2007. Applause rang out from architects, security guards and travelers alike. From some parts of the terminal the view of the mural is obstructed: rather than a mistake, it seems like a conscious attempt to interrupt the sight line, as might happen in any real city. Even the slits on the walls, where the drawing must give way to the air conditioning vents, seem to be a tongue-in-cheek nod to the fantasy at play here: a strange wind blows around this landscape.

Ukranian writer Vitali Vitaliev has said, “A good traveller doesn’t know where he is going, but a perfect traveller doesn’t know where he comes from.”

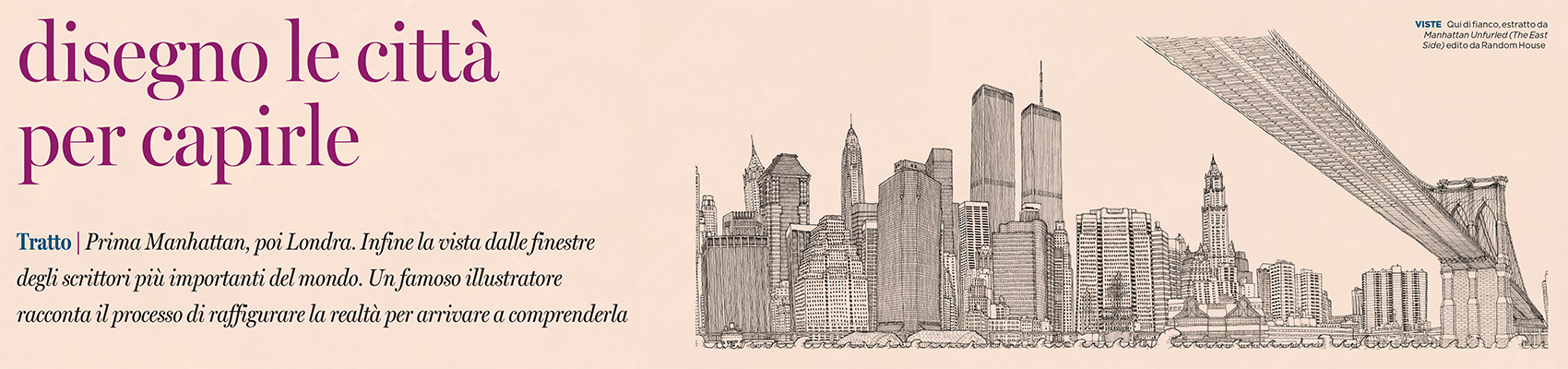

Pericoli’s work is both tactile and clued in. He is very much an artist of the world. He is known for his compelling drawings of the Manhattan skyline and of the view from Central Park “outward.” But his imagination also seems to live in a gyre—for him, cities appear to spin in elaborate circles. He can induce a sort of vertiginous tornado in the viewer. There is turbulence and then there is a touchdown.

We are in a place we knew, but he has made it different for us. In this sense, even more than a traveler, Pericoli is a perfect guide. He leaves people out of his drawings precisely because he knows that they will eventually walk themselves in. They will find their own Dublin. Or Tokyo. Or New York. He opens up the windows of all these cities and invites us to fly outward from them. The skyline, therefore, is our own. He has allowed us that most revelatory moment of creativity when we look up and think that, even if we have once been in that place and have left it, we would one day like to return.

We leave. And we sometimes come home.

Occasionally the walk is only the length of a city block. A departure, if you will. A moment away from the security gate.

Final sketch of Skyline of the World

Visit Colum McCann’s website