by Architectural Record

Up Close with the Cover of the 125th Anniversary issue

Click here to view the drawing page.

by Architectural Record

Up Close with the Cover of the 125th Anniversary issue

Click here to view the drawing page.

Some images and a video from the incredible and intense, 5-day-long May 2016 edition of the LabLitArch in Jerusalem, held in collaboration with The Hebrew University‘s Department of Comparative Literature, the Bezalel Academy‘s Department of Architecture, and Da’at HaMakom (The Center for the Study of Cultures of Place in Jewish Modernity).

Some images and a video from the incredible and intense, 5-day-long May 2016 edition of the LabLitArch in Jerusalem, held in collaboration with The Hebrew University‘s Department of Comparative Literature, the Bezalel Academy‘s Department of Architecture, and Da’at HaMakom (The Center for the Study of Cultures of Place in Jewish Modernity).

Images: http://lablitarch.com/2016/05/lablitarch-edition-in-jerusalem/

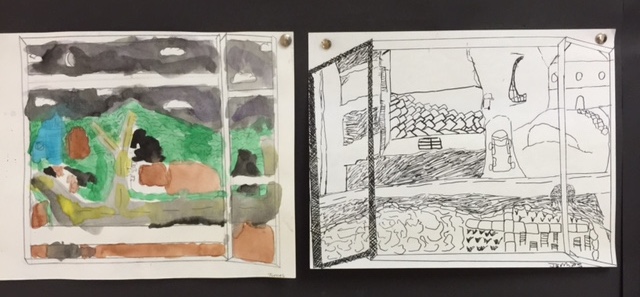

A wonderful series of 4th and 5th graders’ window view drawings from Wiley International Magnet School in North Carolina.

di Ilaria Guidantoni

Abbiamo incontrato questo disegnatore, un narratore attraverso le immagini, alla libreria L’Argonauta libri per viaggiare di Roma qualche tempo fa in occasione della presentazione del suo libro Finestre sul mondo. 50 scrittori, 50 vedute […] e abbiamo deciso di addentrarci in questo mondo di linee e segni, di un grande osservatore.

Come nasce la sua passione per il disegno e quando ha avuto origine? C’è stata un’immagine che ha segnato una svolta?

«Il disegno in realtà è nato con me, o io con lui; nel senso che in famiglia, per via del mestiere di mio padre, ma anche perché mia nonna (da parte materna) era un’artista nascosta — e che a insaputa quasi di tutti dipingeva, faceva intricati e bellissimi arazzi, suonava — il disegno era un linguaggio molto presente, quasi complementare. Non ci sono state quindi vere e proprie svolte, o scoperte. Forse potrei dire di averlo riscoperto un paio di volte: quando avevo 16-18 anni — a quel punto erano parecchi anni che avevo smesso di disegnare e tutt’a un tratto scoprii che mi veniva bene, che mi piaceva. E poi una volta arrivato a New York, a 26 anni — lì mi accorsi che potevo usare il disegno per comprendere (e, forse, raccontare) il meraviglioso mondo in cui ero andato a capitare.»

Quando ha cominciato a dedicarsi in modo serio e poi esclusivo al disegno?

«Appunto, come dicevo sopra, a New York. Mentre ero ancora in Italia, e studiavo architettura, pensavo che il disegno mi sarebbe poi servito semplicemente per poter svolgere il mestiere di architetto. E così è stato: quando ho lavorato nello studio di Richard Meier, a New York, ogni progetto, prima di essere trasferito sui programmi di cad, veniva disegnato a mano, dalle scale al 1.000 fino ai dettagli 1:1. E la mano, come si suol dire, m’è tornata molto utile in quegli anni. Anzi, forse è proprio lì che l’ho addestrata a curarsi delle linee come fossero delle sottilissime e filamentose parole, ognuna importante come le altre e nessuna che predominasse urlando sopra alle altre.»

Come nasce la scelta dei soggetti da ritrarre? È cambiata nel tempo e pensa di cimentarsi in altri ambiti di argomento?

«Mi auguro proprio che mi arrivino altri stimoli o idee in modo da poter variare i miei soggetti o, forse più accuratamente, le mie ossessioni. La scelta è di solito, o almeno finora, una diretta conseguenza di una curiosità, o ossessione appunto. Dapprima fu la città, e nello specifico New York.»

Cosa c’era di quel luogo che tanto l’affascinava?

«Perché me ne ero infatuato tanto? Era in me, solo in me, che dovevo cercare la causa dell’infatuazione? O c’era forse un qualche segreto che avrei potuto scovare disegnandola? Nel cercarne la chiave di lettura, di interpretazione, e una risposta alle domande sopra, ho iniziato a disegnarla da tutti i possibili punti di vista (le lunghe viste disegnate su rotoli), e poi sono entrato nelle finestre dei suoi abitanti per guardarla da lì, e così via.»

Qual è il suo modo di procedere e quali le tappe del suo lavoro? Procede sempre nello stesso modo?

«Dopo parecchi anni credo di poter dire che il mio metodo è sostanzialmente analitico e molto poco, forse troppo poco, istintivo. Se trovo un soggetto che mi interessa, lo studio tramite fotografie e tutto il materiale che può servirmi. “Studiare” per me alla fine non vuol dire altro che far passare del tempo e osservare, non disegnare. Il disegno “arriva” poi, quando so che è il momento giusto, che ho abbastanza informazioni per cercare di sintetizzare quello che ho visto, fotografato o studiato. So che se iniziassi troppo presto finirei per disegnare e quindi descrivere cose che non ho capito, che non ho fatto il più possibile mie. Il disegno al tratto è, purtroppo, un modo di trasferire interpretazione e sintesi; idee e analisi; come in un progetto architettonico, le linee sono dei messaggi chiari, che è meglio non siano fraintesi.»

Cosa l’affascina della visione en plein air e che cosa invece dell’esterno visto da un interno?

«La visione en plein air sostanzialmente mi spaventa. Non sono un disegnatore “performativo”, cioè che si sente a suo agio a schizzare o disegnare con intorno altre persone. Ho bisogno di accumulare informazioni, appunto, prima di poter iniziare. Dall’interno, se dall’interno intendiamo un luogo fisico, una finestra, l’unica differenza è che è più facile raccogliere le informazioni necessarie per poi poter lavorare. Nessuno mi guarda. Se per interno intendiamo metaforicamente la mia mente, allora lì sono molto più a mio agio, coi miei tempi, le mie lentezze, le mie improvvise accelerazioni (inaspettate e rare, ma accadono), e le attese.»

In che rapporto stanno per lei non solo nel risultato artistico l’emozione di quello che vede e il gusto per il dettaglio quasi miniaturistico?

«È una domanda molto complessa. Innanzitutto perché ci sono quelle due parole, “risultato artistico”, che per me sono un mistero e richiederebbero solo loro dieci pagine. Io vedo nel mio lavoro soprattutto quantità di informazioni da trasmettere. L’ineffabile e inquieto equilibrio tra ciò che si vuole raccontare e il numero di linee usate per farlo (questione che credo sia simile per chi scrive) è per me il nodo cruciale. Mi emoziono quando scopro che disegnando quello prima che stavo solo guardando, senza in realtà vedere, mi si apre un mondo che mi sarebbe sfuggito se non mi fossi soffermato sui dettagli. Il gusto per il dettaglio non è mai fine a se stesso, è per trovare il rapporto tra il tutto e le parti.»

E il colore, cosa aggiunge e cosa toglie a suo parere?

«Riconosco che il colore, per chi lo sa usare, dev’essere una grande soddisfazione. A me crea ansia. Non sono bravo, non lo vedo bene, lo uso male, impropriamente. In più sento che mi distrae, o credo che distragga, dalla fatica delle decisioni fatte per includere oppure omettere un dettaglio, o togliere una linea di troppo. Alle volte riconosco che migliora l’impatto di un disegno, perché il disegno al tratto richiede un diverso tipo di impegno da parte dell’osservatore. Ma alla fine mi piacciono entrambi, e mi sento più libero, meno costretto — ovviamente — quando uso del colore. E allora mi dico che dovrei usarlo di più.»

Quando guarda, osserva, poi disegna, infine contempla il disegno mentalmente racconta una storia o vede delle storie, vite, fantasie che animano? Non ha mai pensato di scriverle?

«Ci penso sempre. Forse in fondo le sto memorizzando, o sto memorizzando qualcosa su queste avventure fatte di osservazione priva di parole, per ora, per poi scrivere. Nel caso delle finestre, mi era stato chiesto inizialmente dalla casa editrice di scrivere delle tante finestre disegnate per il libro su New York (uscito nel 2009 con Simon & Schuster), ma mi resi conto poi che i racconti o i commenti dei “proprietari” delle varie viste dalle finestre aggiungevano tutto ciò che le mie linee non potevano dire. Che senza di loro i disegni non erano completi. Dei miei scritti, invece, non avrebbero aggiunto molto, sarebbero forse stati noiosi e autoreferenziali — il rischio più grande che si possa correre.»

Per ritrarre qualcosa le deve piacere o può semplicemente incuriosirla?

«Direi entrambe le cose. Se qualcosa mi piace, però, spesso temo di poterla rovinare disegnandola. Sento più responsabilità, per così dire. Era così per le viste dalle finestre di New York: scegliemmo quelle che raccontavano qualcosa di interessante, nuovo, diverso sulla città, e non viste “già viste”, quelle fotogeniche o più banalmente belle. Il disegno al tratto è in grado di raccontare storie fatte di linee scelte una per una, la fotografia per esempio è meglio attrezzata per rendere il bello con più sicurezza.»

Sta lavorando a qualche altro progetto o almeno idea?

«Dopo l’indicibile sfida della Divina Commedia (l’intera cosmologia in un unico disegno per una nuova edizione della D.C. che sarà pubblicata nel 2016 dalla Loescher), conclusasi non molto tempo fa, mi sto cimentando con un altro bel problema, soprattutto per un architetto: Le città invisibili di Calvino. È una commissione di una casa editrice brasiliana che ha scelto otto città che sto laboriosamente e timorosamente cercando di disegnare. Ma siamo ancora ben lontani. Prosegue invece e continua a produrre risultati sempre più sorprendenti il mio Laboratorio di Architettura Letteraria (www.lablitarch.com).»

Clicca qui per leggere l’intervista direttamente dal sito Saltinaria:

http://www.saltinaria.it/interviste/interviste-arte/matteo-pericoli-quando-il-disegno-narra-intervista-cultura.html

di Vincenzo Latronico

Rane – Il Sole 24 Ore – 29 settembre 2015

Tecnicamente sarebbe

un “workshop interdisciplinare”.

In pratica, è uno

strabiliante esperimento

intellettuale in grado di

mettere insieme le forbici

con la punta arrotondata

e i racconti di Kafka

In un torrido pomeriggio di inizio luglio stavo parlando con due amici di un testo di Amy Hempel intitolato Il Raccolto. Racconta la storia di un incidente d’auto capitato all’autrice, e poi la racconta di nuovo: elencando le omissioni e gli aggiustamenti fatti alla prima versione per renderla efficace e brillante, svelando le piccole insicurezze di chi scrive, le bugie e le vergogne. L’effetto è accattivante e straniante allo stesso tempo. Alla fine la prima storia – quella “romanzata” – non sta in piedi.

«Non si regge», ho detto. «La seconda parte gli toglie ogni punto d’appoggio».

«È vero», ha detto Stefania. «Servirebbe un pilastro».

Non era una metafora per riferirsi a una frase efficace. Stefania parlava proprio di un pilastro. La prima parte del racconto della Hempel era un osservatorio a picco su una montagna, scavato all’interno di un salone più grande che era la seconda, e non si reggeva.

Poi abbiamo aggiunto un pilastro, che Andrea ha ritagliato nel cartoncino vegetale, e allora sì.

Eravamo al Laboratorio di Architettura Letteraria, uno strabiliante esperimento intellettuale portato avanti da Matteo Pericoli, architetto e disegnatore. Tecnicamente è un “workshop interdisciplinare”, ma il termine è un po’ urticante e calza male a una situazione in cui sono presenti in egual misura Kafka e forbici con la punta arrotondata.

Per introdurre il tema del laboratorio, Pericoli cita spesso un brano di Alice Munro: «Una storia non è una strada da percorrere (…) è più come una casa. Ci entri e ci rimani per un po’, andando avanti e indietro e sistemandoti dove ti pare, scoprendo come le camere stiano in rapporto col corridoio, come il mondo esterno viene alterato se lo guardi da queste finestre. E anche tu, il visitatore, il lettore, sei alterato dall’essere in questo spazio chiuso, ampio e facile o pieno di svolte e angoli che sia, pieno oppure vuoto di arredamento. [Questa casa] trasmette anche un forte senso di sé, di essere stata costruita per una sua necessità, non solo per fare da riparo o per stupirti».

L’idea di fondo del laboratorio è che questa metafora – che il percorso del lettore in un libro è simile al percorso di una persona in uno spazio – può essere presa sul serio; e che l’architettura può essere usata come strumento concettuale per analizzare e comprendere una storia, disegnandone un progetto strutturale e costruendone letteralmente un modello.

Strutture, vuoti, scale

In passato i corsi si sono tenuti in varie forme alla Columbia University di New York e alla Scuola Holden di Torino, in scuole superiori statunitensi e all’Università di Ferrara; io ho preso parte a un’iterazione che si è svolta all’interno del festival “Architettura in città” dell’Ordine degli Architetti di Torino.

In passato i corsi si sono tenuti in varie forme alla Columbia University di New York e alla Scuola Holden di Torino, in scuole superiori statunitensi e all’Università di Ferrara; io ho preso parte a un’iterazione che si è svolta all’interno del festival “Architettura in città” dell’Ordine degli Architetti di Torino.

Eravamo in quindici, tutti architetti presenti o futuri a parte me; faceva un caldo brutale fuori dai magazzini OZ, l’associazione che ci ospitava. Dopo una breve introduzione di Pericoli, ci siamo divisi in gruppi in base ai testi che avevamo scelto. Ci siamo seduti a un tavolo, ci siamo presentati rapidamente e abbiamo cominciato a parlare del testo di Hempel. Era come se parlassimo di architettura. Dicevamo tensione, struttura, ritmo, aperture e chiusure, connessioni, passaggi, sequenze, vuoto. Dicevamo scena, che in realtà è il luogo dove le scene narrative si svolgono. Dicevamo climax, che significa scala.

Secondo il grande linguista George Lakoff le metafore non sono casuali: più sono cementate nel nostro linguaggio, più rivelano che l’affinità fra i due campi ha un reale fondamento cognitivo. È celebre l’esempio della matematica, di cui si parla spesso con metafora spaziale (numeri che si seguono, insiemi che contengono); Lakoff ha dimostrato che i processi mentali che attiva nel cervello sono gli stessi usati per orientarsi nel movimento.

Non so se ci sia un qualche fondamento cognitivo nell’idea che una storia è come una casa (ne dubito); quello che so è che parlare di una storia come se fosse una casa è un modo estremamente efficace per comprenderla.

Penso al nostro caso: tre sconosciuti seduti intorno a un tavolo che devono discutere di un testo che hanno letto. Le probabilità che qualcosa vada storto sono altissime: si può finire schiacciati dal silenzio imbarazzato, o smarriti nelle astrazioni sclerotizzate a cui ci abitua la scuola («intenzione dell’autore», «contesto storico»), o bloccati nel pantano del «secondo-me-lei-non-lo-amava-davvero».

A noi non è capitato nulla di tutto questo; la metafora architettonica ci ha indirizzati verso l’essenziale. La Hempel raccontava una storia, e poi l’episodio reale da cui questa era nata: e cioè l’episodio su cui questa si fondava, su cui si basava, che la racchiudeva. Questi sono termini spaziali, e ci è stato chiaro che la struttura del racconto si traduceva in due ambienti fra cui vigeva uno di quei rapporti.

La spirale di Dumas

Mi è venuto immediato estendere questa procedura ad altri testi che conosco e amo.

Mi è venuto immediato estendere questa procedura ad altri testi che conosco e amo.

Democracy di Joan Didion – una storia d’amore raccontata in modo esploso, tornando ciclicamente alla stessa scena madre per poi diramarsi ogni volta in un momento diverso del passato dei due – è un labirinto in cui si ripassa sempre da una stanza centrale, vedendola ogni volta da prospettive diverse.

Il conte di Monte-Cristo di Alexandre Dumas, che racconta di una vendetta preparata per decenni, è una spirale ascendente: visto di fianco, è la storia di un’ascesa vertiginosa, visto da sopra è un percorso che porta esattamente al punto di partenza, e probabilmente finisce in uno strapiombo.

Questo è a tutti gli effetti un modo di visualizzare un’idea astratta, anzi, di toccarla con mano: finito il progetto ci siamo messi a realizzarne un modello. Oltre che essere molto divertente per me che passo la vita al computer (colla! taglierino!), questo ci ha permesso di scoprire aspetti di quell’idea che prima, al solo pensiero, non erano evidenti.

Ad esempio: tutto ciò che non è finito nel nostro progetto – i personaggi, le piccole scene, le battute di dialogo – si rivelava in qualche modo inessenziale; un personaggio poteva essere eliminato, una conversazione allungarsi o svolgersi altrove, ma l’esperienza complessiva del lettore non sarebbe cambiata in maniera cruciale. Questa è una verità che fa rabbrividire critici e teorici, ma che ogni lettore sa bene: in un romanzo, molta della superficie è secondaria o comunque rimpiazzabile, purché lo scheletro, progettato in ogni dettaglio e calibrato al microgrammo, resti inalterato. È quello scheletro che si costruisce nel modello. Vederne una prova sotto i miei occhi è stato sbalorditivo.

Ancora più sbalorditivo è stato rendersi conto che, alla fine del laboratorio, all’esposizione dei modelli, mi trovavo in una stanza con quindici persone che avevano passato tre giorni a discutere di teoria letteraria: ed era stato, inspiegabilmente, divertente e proficuo.

Lettori sudati

Credo che sia qui la rilevanza profonda del laboratorio, che va ben al di là delle sfere ristrette di scrittori e architetti e ha a che fare col modo in cui si comprende e si insegna la letteratura.

Credo che sia qui la rilevanza profonda del laboratorio, che va ben al di là delle sfere ristrette di scrittori e architetti e ha a che fare col modo in cui si comprende e si insegna la letteratura.

Tempo fa, sulle pagine di questo giornale, lamentavo la pesantezza e l’inefficacia del suo insegnamento scolastico, che spesso la fa apparire come una montagna inespugnabile anziché come una fonte di gioia. Sostenevo che era anche per questo che si leggeva poco e male. Di recente mi ha risposto Giusi Marchetta con uno splendido saggio (Lettori si cresce, Einaudi 2015) in cui argomenta che è un bene che gli studenti vedano la letteratura come una montagna, perché la scuola deve opporsi al meccanismo della gratificazione istantanea e insegnare che i premi importanti vanno sudati.

La sua tesi mi ha convinto, eppure restavo – resto – dell’idea che le montagne siano spaventose e inospitali, e che se la letteratura viene mostrata come tale gli studenti continueranno a preferire le spiagge di Instagram e le piscine gonfiabili di Candy Crush.

Al laboratorio – facendo teoria letteraria con cartoncino e matite – ho visto un’altra possibilità. Su quella montagna ci si costruisce una casa.

Leggi sul sito del Sole 24 Ore:

https://st.ilsole24ore.com/art/cultura/2015-09-28/laboratorio-architettura-letteraria-184136.shtml

di Vincenzo Latronico

“Ma che cos’è una vista? Né un oggetto, né un posto, forse l’intersezione fra entrambe le cose e una persona che vi si trova; basta spostare appena lo sguardo, avvicinarsi di mezzo passo, per trasformarla drasticamente. Per questo una fotografia non potrebbe mai renderla in modo fedele: mostra ciò che c’è, non ciò che si vede. I disegni di Pericoli sì. Essenziali e privi di sfocatura prospettica, nascono da un lavoro certosino basato su decine e decine di scatti diversi; il tratto è allo stesso tempo dettagliatissimo e un filo tremulo, come per ricostruire i meccanismi dell’attenzione.”

“Ma che cos’è una vista? Né un oggetto, né un posto, forse l’intersezione fra entrambe le cose e una persona che vi si trova; basta spostare appena lo sguardo, avvicinarsi di mezzo passo, per trasformarla drasticamente. Per questo una fotografia non potrebbe mai renderla in modo fedele: mostra ciò che c’è, non ciò che si vede. I disegni di Pericoli sì. Essenziali e privi di sfocatura prospettica, nascono da un lavoro certosino basato su decine e decine di scatti diversi; il tratto è allo stesso tempo dettagliatissimo e un filo tremulo, come per ricostruire i meccanismi dell’attenzione.”

Continua a leggere: https://st.ilsole24ore.com/art/cultura/2015-05-27/con-vista-205117.shtml

Looking Out, Looking In

By Jessica Gross

LA Review of Books, December 1, 2014

EARLIER THIS YEAR, I interviewed the children’s author Lois Lowry for The New York Times Magazine. My favorite bit of our conversation, which didn’t make it into print, came when I asked her to describe what she sees out her window when she works.

“My house here was built in 1769,” she said. “I look out from it onto a meadow and gardens and apple trees and sometimes deer in the meadow and sometimes wild turkeys walking through the grass.” It was this image of Lowry — who in my mind had been a supernatural force — that made her appear to me as real.

It was with great excitement, then, that I learned Penguin would publish a book called Windows on the World: Fifty Writers, Fifty Views. Authors including Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Teju Cole, and Sheila Heti have written short texts to accompany line drawings meticulously executed by artist Matteo Pericoli. The writers live in towns and cities across the world, and their windows look out on treetops, rooftops, mosques, churches, private gardens, and other people’s windows.

This project, conceived of by the artist, ran on The New York Times’ Op-Ed page from August 2010 through August 2011, and continued in The Paris Review Daily as well as in other venues. Pericoli, who was born in Milan and moved to New York in 1995, is trained as an architect; his background comes through in his work, rich and exacting, drawn from many images of each window. In every illustration, the window floats on the white space of the page, absent surrounding walls and details. “It is crucial that these window views should be rendered in pen and ink, in lines, rather than in photographs,” Lorin Stein rightly notes in a lovely short preface.

Labor, it seems to me, is one of Pericoli’s hidden subjects. That is part of the meaning of the hundreds of leaves on a tree, or the windows of a high-rise: They record the work it took to see them, and this work stands as a sort of visual correlative, or illustration, of the work his writers do.

While Pericoli’s mission is clear and uniformly expressed, it seemed to me, at first, that the writers could have been given more direction (a frame, if you will). We don’t know how Pericoli chose or approached them or what he had in mind: in his introduction, he states that he simply asked writers “to describe their views.” The result is that the whole lacks cohesion, and some texts complement the drawings better than others.

But perhaps, in a way, this is appropriate to the material: what comes through is how differently these writers approach their varied windowscapes — which comes down to their approach to the work itself. Some intentionally avoid looking out the window in order to dwell in their imaginations. Daniel Kehlmann writes from Berlin: “I try to ignore this view. When I’m at my writing desk I turn my back to it.” Etgar Keret, in Tel Aviv, does the same: “When I write, what I see around me is the landscape of my story. I only get to enjoy the real one when I’m done.”

This approach is best described by Nadine Gordimer:

My desk is away to the left of the window. At it, I face a blank wall. For the hours I’m at work I’m physically in my home in Johannesburg. But in a combination of awareness and senses that every fiction writer knows, I am in whatever elsewhere the story is in. […] I don’t believe a fiction writer needs a room with a view. His or her view: the milieu, the atmosphere, the weather of the individuals the writer is bringing to life. What they experience around them, what they are seeing, is what the writer is experiencing, seeing, living.

Other writers live somewhere in between: they shun the window while they work, but use it to reset. “I turn away from the window. My desk faces a wall covered with images, notes, timelines, vaudeville photographs, and playbills,” Marina Endicott writes from Edmonton in Alberta, Canada. “When my eyes blear and I cannot focus any longer, the window is a way for my mind to blink, to clear my vision.” And from the late Elmore Leonard, who lived in Bloomfield Village, Michigan: “Distractions are good when I’m stuck in whatever it is I’m writing or have reached the point of overwriting. The hawk flies off, the squirrels begin to venture out, cautious at first, and I return to the yellow pad, my mind cleared of unnecessary words.”

Of course, no one can simultaneously look outside and write, an act that requires the mind be elsewhere and the eyes be pointed toward the page or screen. But some writers purposefully use their views for inspiration. In Lagos, Nigeria, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie claims, “When my writing is not going well, there are two things I do in the hope of luring the words back: I read some pages of books I love or I watch the world.” She describes her view as “choked with stories, because it is full of people. I watch them and I imagine their lives and invent their dreams.” And Andrea Levy confides:

When I was young my mum used to complain that I spent too much time daydreaming. That was because I liked to stare at the sky. She thought that while I was dreaming I could be doing something useful as well, like knitting. Now that I am a writer, I have the privilege of daydreaming as part of my job. And I still love to gaze at the sky. The view from my workroom in my North London house has a lot of sky, and I couldn’t work without it. There are never any structured thoughts in my head when I look up. They just come and go and change shape like the clouds.

¤

My attraction to Windows on the World is part of a larger obsession with artistic process. Often, when I interview a writer or comic or actor or singer or chef, I harp on the how: How did you know where to begin the story? How did you learn to sing in a southern accent? How many versions of this joke did you go through before you hit on the one that worked?

Admittedly, I’m analytical by nature, but this proclivity to investigate the mechanics of creativity appears to be widespread, as evidenced by the excitement that accompanied last year’s publication of Mason Currey’s Daily Rituals, and the fact that Maria Popova’s Brain Pickings post on writers’ daily routines was the most read and shared in her website’s history.

The obvious motive — to discover how artists work, as if we might successfully copy their routines — is only part of our fascination; we’re also driven by fear. Art holds sway over us in ways that we don’t understand. This is what gives it power, of course. But the urge to deconstruct it, to decipher not only its meaning but also the conditions in which it was created, is a way for us to wrest some control — or to imagine that it’s possible to do so. We want to know how the trick is done.

Then, too, it’s reassuring when artists allow us to see their imperfections: perhaps there is hope for us after all, despite our many faults. At their best, the drawings and texts in Windows on the World make writers real and human — the Lois Lowry effect — while still leaving room for mystery and fantasy. Shelia Heti, a writer I particularly admire, lives in Toronto. Pericoli has drawn her rectangular, double-hung window, with what look like vines stretching across its panes. Beyond them is a street, and on the other side of it is a house with a planting bed in front of it. “Can you see that beautiful shrub?” Heti writes. “It has no bald patch, right?” She tells us that the “shy, moustached Portuguese man” who lives across the street has stood staring at the hedge’s bald patch for hours a day, and Heti would periodically look out at him looking at the shrub. Finally, this summer, the patch disappeared. “He stares at his shrub as I stare at my computer,” Heti writes. “Our bodies are opposite each other every day, and we stare at things, and wait for the emptiness to fill in.”

This seems as apt a companion to the drawing as any, and as apt a description of the writing process. Heti’s window, pictured on the opposite page, stands alone, urging us to imagine the wall space and the room that surround it. We imagine the man, who is not depicted; we imagine Heti, writing. There is no color, so while the lines are meticulous, they also urge us to fill in the view in our minds. Heti’s text, short as it is, presents a snapshot of her, looking over the screen of her laptop at her companion, the stranger — but only that. We know enough to feel reassured our writers are real, but not so much we can’t fold them into stories of our own.

Read from the LARB website: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/looking-out

By Maddie Crum

BOOKS, HuffPost, November 18, 2014

Matteo Pericoli is an architect and illustrator. He began sketching window views after moving out of an apartment he’d lived in for nearly a decade, and realizing that he’d never gaze out at the same spot again. His latest book, Windows on the World, collects his drawings of writers’ window views, accompanied by their short descriptions of the views’ importance. Some capture the quotidian — power lines and garden supplies — while others feature major historical landmarks. Pericoli spoke with The Huffington Post about his project and his favorite window views.

What inspired you to begin your Windows on the World project?

After all these years spent drawing window views, I’ve come to the conclusion that contemplating a window view isn’t so much an action directed outward, but inward, one of reflection. The view looks back at you, and asks: “Why are you here? Is this really the place (in the world, in your life) where you want to be? How did you get here? (Both practically and metaphorically.)”

That’s what happened to me ten years ago when I was moving out of our Upper West Side apartment and suddenly realized that I would have lost forever the window view I’d been looking at (mostly unknowingly) for seven years. That’s when I realized that that particular view symbolized my life path and decisions made up to that point. And that’s when I told myself, “Now I have to draw all of the window views of the city!” Obviously I never did that, I just drew 63 (out of a hundred plus I had visited) that were after published in a book called The City Out My Window: 63 Views on New York. In the seven years prior, I had worked on long scrolls depicting Manhattan as seen from its surrounding rivers and from Central Park. My goal had always been to try to draw the whole city, yet I never imagined that what I had been looking for was instead the reverse process, i.e. to draw how people see the city, rather than what the physical city looks like.

I decided that there are two kinds of window views: active and passive. If you feel that your choices have brought you to where you are at that very moment in time and space (i.e. the viewpoint provided by your window), then the narrative around the view is active. If that’s not the case, it’s a passive view. Children’s window view drawings and texts are among the most telling because theirs are quintessentially passive views, thus we can infer a great amount of information about how children perceive their place in the world from their particular perspectives (literally).

When I was working on the New York window view book, I realized that writers had a similar relationship to their views as mine. Mostly stuck at their desks, they would either position themselves near a window in order to take in as much as possible, or would consciously choose to protect themselves from it. And when I asked them to describe their views, something extraordinary happened: all the elements that I had been able to capture in my drawings were complemented — even augmented — by their words. This was the simple premise of the Windows on the World project: drawings of writers’ window views from around the world accompanied by their texts — lines and words united by a physical point of view.

You’ve said that photographing the windows didn’t always suffice. What you wanted to capture was the way you emotionally perceived your view, too. So what was the process of drawing writers’ windows like? (Did you ask them to submit photos, describe them with words, etc.?)

Back to my Upper West Side view from ten years ago. When I realized that I couldn’t leave the view behind, that it was too much a part of me, I thought, “Wouldn’t it be great if I could peel an imaginary film off the window and take everything with me, window frame, glass, view, and all?” I tried photographing the view, but (perhaps I am a bad photographer, or maybe for technical limitations) what I was getting was either the window itself or what was beyond the glass, not both, or at least I was not getting my mental image of it. If you open the window and take a picture, you see an urban landscape; if you photograph the frame, you mostly see the frame. A window view is both.

So just like with my long skyline drawings, the only way for me to reproduce a window view is to obtain as many photographs as possible, use them to mentally reconstruct the view, i.e. the space between the sheet of glass and all the physical elements that constitute the view, and rebuild it as a line drawing. Often the writers’ photos came with descriptions, but often it would end up the other way around: i.e. I would be the one describing the window views to them with my drawing.

Drawing (and especially hard line drawing) is first and foremost a process of synthesizing information. Each line is the result of a selection, a series of omissions in order to tell the most with the least. It’s a process that requires a lot of preparation and investment and yields a “low artistic return,” so to speak. For example, Saul Steinberg’s drawings are among some of the most beautiful works of art, and yet the majority of them are “simple” line drawings with most of the effort made before each line was placed on the paper.

Do you find that there’s often a disconnect between the way we conceptualize a space and the way it “actually” looks?

This is an interesting question. Prior to forming a concept of space, it must first be perceived. And we do that all the time. I am doing it right now, as the artificial light just in front of me is reflecting by the walls around my tiny workspace and the sound of my typing on the keyboard also reverberates off them. With my peripheral vision I monitor the light coming from a not-so-close window to my left. And we do the same when we walk out in the street or through a square (by subconsciously selecting to walk closer to the buildings rather than in the middle of the open space). Whenever we encounter a space (which happens hundreds of times a day), we take it in via our senses. So we actually experience and therefore know architecture much more than we think we do, because space — i.e. nothingness — is constantly being perceived. We see what’s constructed; we perceive what’s not there: space.

In fact, when we talk about what a space “looks like,” we often refer to the physical, tangible aspects of architecture — i.e. what forms space: walls, openings, glass walls, slabs, roofs, etc. — rather than space itself. Just as in other disciplines, what is not physically there is often as important as what is there. A window view is nothing but a hole in the wall through which we can form an idea of the world we live in.

I teach a course called Laboratory of Literary Architecture (LabLitArch.com) in which we imagine removing all the words from literary texts and look at what is left. As in architecture, once you remove the skin — the “language” of walls, roofs, and slabs — all that remains is sheer space. In writing, once you discard language itself, what’s left? What we discover is that the use of architectural metaphors to describe literature (e.g. the architecture of a novel) is not a coincidence: the effort of writing, putting a word after the other in order to build sentences, is very similar to that of constructing a building. The words are used to envelop a literary space that is perceived by the reader, very much like architectural space. By building an architectural model of the literary structure we simply reveal this process.

What were some of the most compelling responses you received from authors?

Receiving the texts from the writers, especially after they had seen my drawing of their window views, was always a truly exciting moment. It was like the closing of a circle; everything made sense. All the things I had stared at, and then drawn, trying to make sense of every single detail, would finally come together. Sometimes, and when it happened it was a lot of fun, someone would thank me for having revealed his/her window to him/her. I recall Marina Endicott, who had doubts about her view being as good as the others, telling me, “You were right, I no longer have view envy.” That was so nice. It’s as if we judge views only by how photogenic they are. Until Ms. Endicott had the chance to write about her view, it had not been so visible to her.

It does happen that sometimes we need to be shown things that are near us to notice them. Or that we notice them when they are gone. And often that’s the case with a window view. It’s hard to sit down in front of it and pay full, true and dedicated attention to it. I mean, it’s always there, I can do it any time I want, why take the time to pause and look? And that’s when things slip by in life. That’s why I would love to go back to my view when I was a little kid growing up in Milan and look at it now, with this recent window obsession of mine. I am sure that, like the sudden resurfacing of a familiar smell, a wave of past and intense feelings would rush through me. Isn’t that nice?

What does your own workspace look like? Do you have a view that you enjoy?

My workspace is the former inside of a walk-in closet. Actually, it’s no longer the inside of the closet as the space now opens up into our bedroom. When we moved in, we tore down a wall between the closet and the bedroom to create my workspace, so technically I am neither in the bedroom nor inside the closet, but kind of in between. My computer desk, i.e. where I am now, is right in front of the door of the former walk-in closet, which can’t be opened now. The most beautiful thing about my workspace is that I had someone cut out a small 14” x 10” glass-less opening in the door just in front of where I sit. This “window” has a small door of its own which can only be opened from the inside, i.e. by me, with a little latch and it’s exactly at the height of my daughter Nadia, who is eight now. So when I hear “knock, knock” and I open my small “window,” I see her smiling face occupying the whole view. Should we ever leave this place, this is the view I’ll miss more than any other.

Orhan Pamuk’s view of the Aya Sofia is breathtaking — he writes that he’s often asked if he grows tired of such a beautiful view, and he says no. On the other hand, Karl Ove Knausgård says he enjoys repetition, and prefers his more mundane view. Do you think an ideal view is awe-inspiring, or commonplace and meditative — a way of clearing our minds?

I don’t think there is an ideal view. There are probably ideal views for different occasions and for different people. For example, if I am happy someplace, at that very moment in time, I know that I’ll absorb the view I am looking at (whatever kind it may be) and turn it into a fantastic view, one that I’ll associate with a positive moment in my life. I think that views do serve as a kind of reset button, the same as when we blink; we need a moment to pause to then move on. For that purpose, all views are the same, because we don’t actually pay attention to them when we look at them, we are just using them.

If you want instead to spend time observing, obviously expansive and photogenic views are great. But being awe-inspiring means that they are often great landscapes, and as a result do not necessarily make great drawings, because a line drawing will not add anything to the landscape. If I have to draw a view, I look for intricate, unexpected, urban (more often than rural, but it’s not a rule) views that offer unique perspectives onto the world. Orhan Pamuk’s view has the compositionally incredibly important mosque right there, just outside the window. Yes, beyond it it is breathtaking, but without the mosque and the two minarets just beyond the terrace, it would be much less interesting (for me). For the New York window view book, I visited an amazing apartment overlooking Central Park. The view from the living room window was so spectacular that I realized I couldn’t draw it. I knew the drawing wouldn’t have added anything that we didn’t already know about how beautiful Central Park is when viewed from a high floor. On the other hand, a friend almost refused to open the curtains to show me his view of a derelict fire escape above a small courtyard facing other windows and another fire escape. I spent days drawing all the bricks of the opposite building and all the squiggly lines of the fire escapes and, well, he ended up loving his view afterwards. He even told me that he started keeping the curtains open in order to take his view in!

Do you have a favorite window or view?

Of course. I see it every day when my daughter returns from school and knocks on my mini closet-door-window.

Read from the HuffPost website: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/windows-on-the-world-book_n_6173178